BY August 5, 1914, hours after Britain’s declaration of war, Territorials of the West Yorkshire Regiment were reporting for duty at Belle Vue Barracks, off Manningham Lane.

“Almost to a man the Bradford Territorials were ready to answer their country’s call,” declared the Bradford Weekly Telegraph on August 7.

Under the modest headline ‘Busy scenes at Belle Vue’, the newspaper described Territorials bedding down wherever they could, with a blanket for comfort and their kit bag for a pillow: “The orders for the day, post yesterday (August 6) included the announcement that entrenching implements would be served out, but also - a grim item - that identity discs were distributed. Worn inside the tunic, these serve an obvious purpose in case of the worst calamity.

MORE 'REMEMBERING THE FALLEN' STORIES

“And another thought-compelling matter is contained in the paybooks which were handed out this morning. At the end there is a ‘short form of will’. Still, nobody allows little things like this to damp his ardour".

At the outbreak of war, Britain’s standing army consisted of just over 247,000 men. Reservists, who had military experience, and Territiorials, totalled just over 424,000. In 1914 the Army could call upon just over 700,000 men.

The French alone had nearly 1.7m men under arms, the Germans nearly 1.9m. The British Expeditionary Force of 150,000 sent into Belgium to fend off the German westward thrust was regarded as inadequate especially by the French.

The French were right. By August 24 British troops were pulled back from Mons where they had suffered a withering German attack.

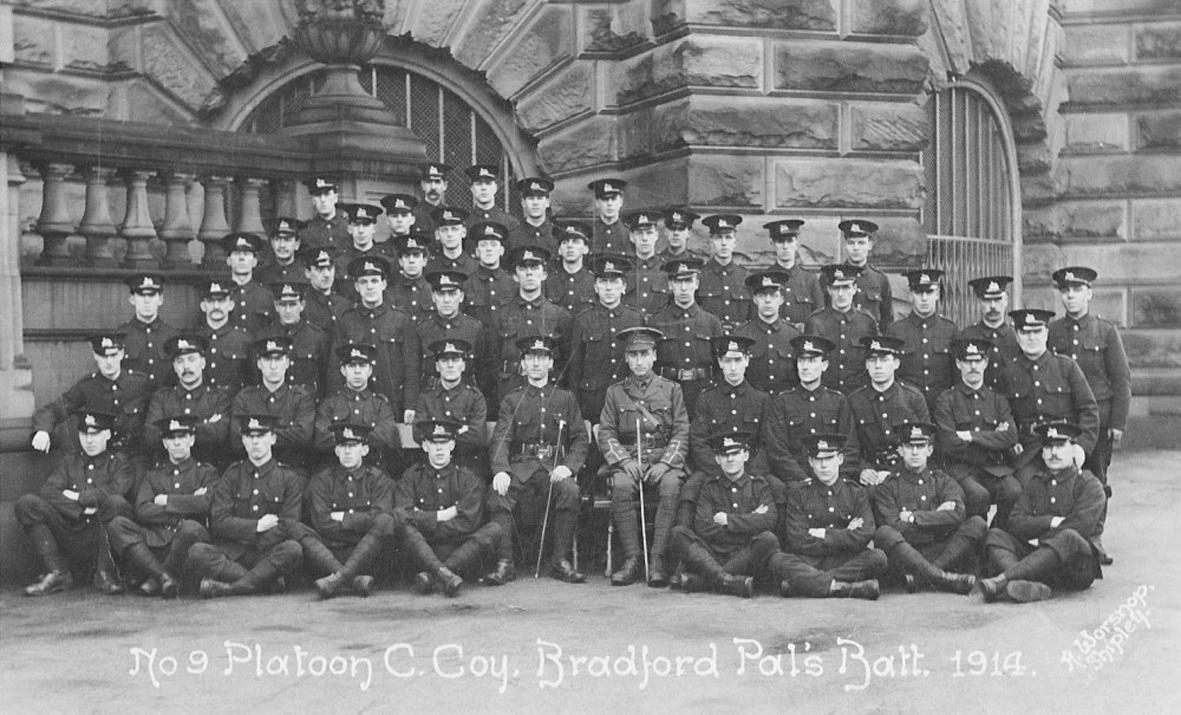

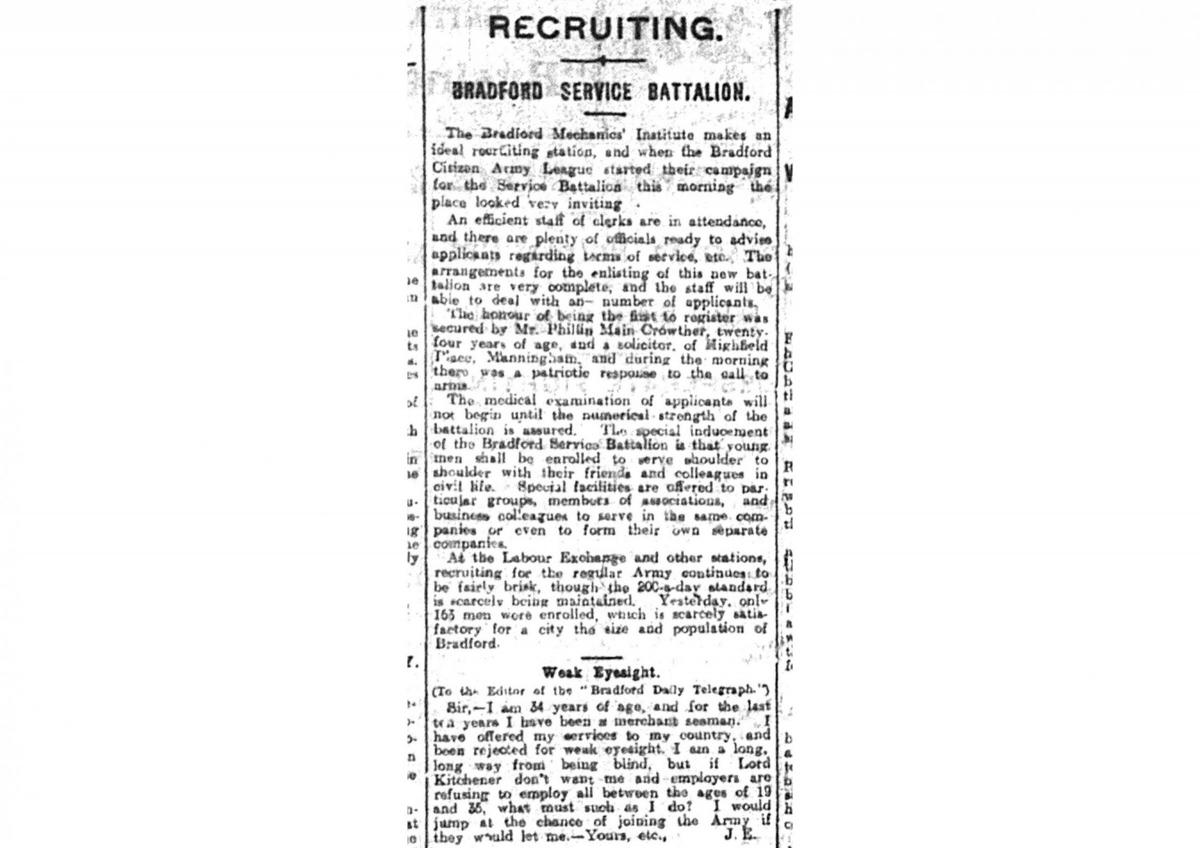

Lord Kitchener realised that something dramatically patriotic was needed to recruit more men. ‘Your Country Needs You’ was the message on posters of Kitchener’s moustachioed face. The recruitment drive worked. The two battalions raised became the 16th and 18th Battalions of the West Yorkshire Regiment - the Bradford Pals.

In February 1916 the Pals were shipped from Egypt to Marseilles then taken to northern France to prepare for what was intended to be ‘the big breakthrough’. On July 1, 1916 one of the most costly battles in history began. It lasted until November.

When the British infantry attempted to cross no-man's land on the first day, along the 14-mile front from Serre in the north to Maricourt above the Somme river, the artillery barrage failed to destroy enemy trenches and barbed wire defences. The first day casualty rate was the highest ever experienced: 19,240 killed out of 57,470 casualties. Among these losses were men of 16th and 18th West Yorkshire Regiment - the Bradford Pals - and other men from Bradford who served in other Battalions of the West Yorks Regiment and other Regiments of the Army. Of an estimated 1,017 casualties, some 282 were killed or later died of wounds.

Our Territorials in 6th Battalion West Yorks (who are commemorated in a window of Bradford Cathedral) also had a torrid time on July 1. Remaining on the Somme, the Territorials again suffered heavily on July 25 and September 3. Alongside them were other local men serving in the West Riding Artillery which had been involved in the barrage which began on June 24, 1916.

Several hundred local men served with the Duke of Wellington's Regiment (especially from Keighley, Silsden, Queensbury, Wibsey and Wyke), and Bradfordians served in numerous other Regiments from all over the country, as well as with Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African forces.

Among the casualties of the first day were many who were to die of their wounds in the days and weeks which followed. The Bradford World War One Group knows of many who were buried in cemeteries along the route the Pals took as they were withdrawn on July 3, hugely depleted in numbers, to make their way north. Some died in hospital in Britain, and could be brought home to Yorkshire for burial.

The battle of the Somme raged on until November 18, by which time both sides were exhausted, severely depleted of men and resources.

The final shot, the last shell, the ultimate bayonet thrust took place before the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918; but those wounded and maimed in the Great War continued to die long afterwards.

Back home in Yorkshire, families were realising the full horror and cost of modern warfare, although many didn't know the fate of their husbands, sons and brothers for some time. The newspapers in July and August 1916 are full of plaintive pleas for news. It is said that there was not a single street in this city and the wider Bradford district - no sports club, no church or chapel - that remained unaffected. Men of all backgrounds, from all walks of life, families of wealth or near-poverty, were equally affected.

Four-and-a-half months later, by the end of the offensive, nearly 96,000 men were killed or missing. The figure includes men from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Undivided India, the West Indies, from across Britain and from Bradford.

No-one knows for sure how many Bradford Pals were lost on July 1, as they attached the heavily fortified village of Serre, as record-keeping in the chaos of battle was difficult. But after much research, the Bradford World War One Group believes approximately 1,400 men from this city went 'over the top' and 1,017 were either killed or injured. And of those who lost their lives on the Somme,120 were men of the 6th Battalion, 192 the 16th Battalion (1st Pals), 140 the 18th Battalion (2nd Pals) and 193 from the Duke of Wellington's Regiment. Nearly 500 men from Bradford were serving in other Battalions when they died.

More than half the Pals and Territorials and Bradford men from other regiments have no known grave and are remembered on the Thiepval Memorial as the 'Missing of the Somme'.

Perhaps three times the total number who died were wounded, some of whom returned with life-long physical injuries. Many others who were to survive would never escape their thoughts, memories or nightmares.

The Cenotaph in Bradford city centre was dedicated, on July 1, 1922 - the sixth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. The sense of loss felt in Bradford was still very raw. In 1925 the Telegraph & Argus reported:

"Weeping mothers, their hands clasped in those of fatherless little children, laid flowers in this sacred place in memory of loved husbands, aged couples sorrowfully mounted the steps, their hearts aching with poignant yet proud remembrance of their heroic sons".

MORE NOSTALGIA HEADLINES

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here