Jim Greenhalf reviews a new book which chronicles the eventful history of Valley Parade, home to Bradford City for the past 125 years

Before the afternoon of May 11, 1985, diehard Bradford City supporters on the open-air Spion Kop used to chant at opposing supporters: “This is the Valley, the Valley of death!”

Perhaps it was an ironic twist on Tennyson’s poem about the gallant futility of the charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War. At Valley Parade the hopes of City supporters were likely to prove as futile as they hoped the fortunes of rival teams would be. Gallows humour evolved out of enduring terrible weather, spartan facilities and severely fluctuating results.

That particular chant vanished from the ground after the fire on that spring Saturday, which killed 56, injured hundreds and added a permanent scar to the collective consciousness of Bradford.

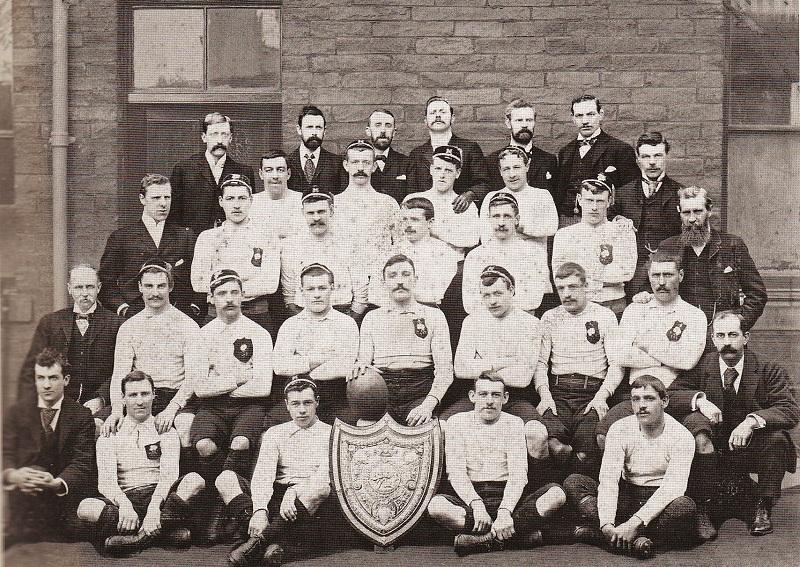

Part of the stadium vanished as well, as is shown in David Pendleton’s new book, Paraders, a 125-page chronicle in words, pictures, diagrams and maps, of the 125-year history of Valley Parade, which started on September 25, 1886 with a rugby union match between Manningham Football Club and Wakefield Trinity.

Nine years later, Manningham was instrumental in the breakaway formation of the Rugby League and in 1899 won the Northern League’s first-ever championship. To this day, the fans of Bradford City and Bradford Bulls continue to argue about ground-sharing.

Tradition, colours and ground are the unifying themes out of which a football club and its fans find a common identity, David says in his introduction. That is especially true of Valley Parade.

The two periods of administration in 2002 and 2004 and the loss of ownership of most of the ground have made City’s fans acutely aware of how much the fate of the club is inextricably tied up with the fate of the ground.

Paraders is a reminder that this is not just a consequence of relegation from the Premier League. Building a ground on the side of a steep hill was always likely to be a slippery slope.

“The financial measures, though necessary, had prevented any chance of strengthening the squad. Performances on the field dipped as a result and naturally attendances fell, which placed even more pressure on finances...”

David could have written that about Bradford City’s plight at any time in the past nine years. In fact, it describes the decline of rugby league-playing Manningham Football Club in 1900, three years before Bradford City started playing professional football at Valley Parade.

How and why the club was formed can be found in chapter two, which concludes with the story of how on May 25, 1903, Bradford City FC joined the Football League without having played a match, but until 1908 was known officially as Manningham Football Club.

The colours of claret and amber were adopted by the football team, Manningham’s hoops becoming City’s stripes in 1904. City’s first ever league match at Valley Parade on September 5, 1903, against Gainsborough Trinity, was filmed by the Mitchell & Kenyon company and shown the following Friday at St George’s Hall.

It was shown again, 100 years later, at the-then National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, as part of the club’s centenary celebrations organised by David Pendleton.

Since the 1985 fire, Valley Parade has undergone several transformations, from what football writer Simon Inglis described as a First World War ‘Sopwith Camel’ of a ground – all struts and wires – with a crowd capacity of 11,000, to the cantilevered 25,000-capacity landmark of today.

But right from the start, almost, the future of Valley Parade was in doubt. In May 1907, for example, there was talk of an amalgamation with Park Avenue-based Bradford FC – the rugby league club formerly known as Manningham FC. The Park Avenue ground, it was argued, had superior facilities. City’s fans were having none of it.

“Without doubt, the bitter rivalry that existed between Bradford and Manningham during their rugby years cast its shadow over the debate. Despite several prominent members of Bradford City’s board being in favour of the merger, the ‘Valley Parade sentiment’ won the day and City’s members rejected the amalgamation by 1,031 votes to 487.”

Instead of abandoning Valley Parade, the club spent £1,000 on improving the main stand. Work was completed in late January 1908, the year City were promoted to the First Division, the year which heralded the club’s golden age that included winning the FA Cup in 1911. The main stand, symbol of that golden age, lasted until May 11, 1985.

The fire disaster wasn’t the only physical event to hit Valley Parade. Gales in 1925, 1927 and 1928 tore off portions of the roof on the old Midland Road ‘cow shed’. Structural faults in the floodlight pylons in 1983 culminated in the collapse of one of the towers on February 1. Then in the summer of 1983, the future of the ground was clouded in doubt yet again as the club went bust with debts of nearly £400,000.

Should we stay or should we go? That has been the question since the fire. It is still being asked. Former T&A City correspondent David Markham, writing in the Christmas edition of the City Gent, the fanzine David Pendleton used to edit, says: “I know there are some people who would like City to look for a new ground on the north side of the city or in the Aire Valley, say Shipley or Baildon, where the club’s support traditionally comes from...

“More recently, the Council tried to entice the club to be part of the Odsal Sporting Village project until that scheme died a death through lack of money...”

David Markham, who has been going to Valley Parade since October 1948, doesn’t want to go anywhere else to watch City. Nor does David Pendleton, judging by the final sentence in his book.

“For many Bradford City is Valley Parade and Valley Parade is Bradford City.”

* Paraders: The 125-Year History Of Valley Parade, by David Pendleton, is published by bantamspast at £16.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article