In January, 73-year-old Valerie Buckley wrote to us asking if we had any information about the men of the 8th Battalion, Duke of Wellington Regiment, who fought and died at Gallipoli. Her grandfather Henry Miller was one of them.

In the census for 1911, Henry Miller, a boiler stoker in a wool combing factory, lived at 23 Raglan Street, Laisterdyke, with his wife Laura, and their two sons David and Fred.

At the time of his death four years later, the family was living at 103 Kershaw Street in Bradford Moor.

After Britain declared war on Germany in August, 1914, Henry Miller joined the Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment) and served in the 8th Battalion. He was killed on the shores of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey, in August 1915.

Last May eight members of the Bradford World War 1 Group walked the battlefields of Gallipoli and took photographs, included here. Group secretary Tricia Platts takes up the story of the campaign and the fate of Private Miller.

“The 8th Battalion was formed in Halifax in August 1914 and drew volunteers from across the West Riding. Many men from the Low Moor/Shelf side of Bradford travelled to the Halifax barracks to enlist – probably on the bus.

“The Battalion trained locally, and then at Belton Park, Grantham, in November and December, and then Witley Camp, Surrey, in April 1915. In July the Battalion, as part of the 11th (Northern) Division of the British Army, embarked from Liverpool for Gallipoli.

“The disembarkation point for Henry’s Battalion on Gallipoli was at Lala Baba on Suvla Bay. British troops had first landed in Gallipoli on April 25, but the battle had come to a standstill.

“The Division which landed in August was intended to complete a victory over the Turkish force which would enable allied ships to pass through the Dardenelles into the Black Sea unmolested by Turkish guns from the Gallipoli shoreline. The Allies could then link up with Russian forces around the Black Sea. The project (Winston Churchill’s idea) was to fail.

“The fighting terrain was unlike anything previously experienced by British troops and battles were fought out in tiny areas. The peninsula is only ten miles at the widest point and is about 45 miles long.

“It is a rocky, scrub-covered area with little water or natural cover for troops. The hills are steep-sided and are cut into deep gulleys and ravines. Along the spine of the Peninsula are many peaks and valleys, which confused inexperienced map readers.

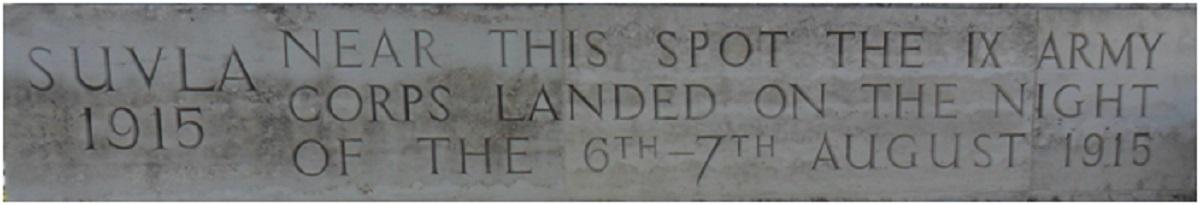

“Henry’s Battalion landed at Suvla Bay, one of the most northerly beaches on the western side. Although the landings there on August 6 and 7 caught the Turks by surprise, Divisional orders meant that the men moved inland too slowly enabling the Turks to occupy the heights overlooking the British positions on the beaches.

“Henry may well have been involved in an attempt to gain the higher ground of Scimitar Hill. This was initially successful, but Henry was to die on Monday, August 9, in the fight to hold on to the advance. The Turks regained the position on August 10. Five days later Lieutenant-General Sir Frederick Stopford was dismissed and replaced by Major-General Beauvoir de Lisle.

“Throughout the summer and autumn, allied troops remained, more or less static, in the most dreadful conditions – too hot, exposed and fly-ridden in the summer months, too cold, wet and exposed in the winter.

“The terrain and close fighting did not allow for the dead to be buried. Flies and other vermin flourished in the heat, which caused sickness of epidemic proportions.

“In October 1915, winter storms caused much damage and human hardship and in December, a great blizzard – followed by a cataclysmic thaw – caused 15,000 casualties throughout the British contingent, and no doubt something similar on the Turkish side.

“Of the 213,000 British casualties on Gallipoli, 145,000 were due to sickness – chief causes being dysentery, diarrhoea, and enteric fever (typhoid, a bacterial fever caused by taking in contaminated food or water).

“British, Australian and New Zealand troops began an orderly withdrawal in December 1915, and all troops had left by the end of January 1916. No lives were lost during this operation – about the only success of the entire, disastrous campaign.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article