From December this year, Bradford Central Library is expected to have a new home in what’s known as the ‘banana building’ opposite the City Park.

Reportedly, up to £8m is going to be spent converting the Central Library building above Prince’s Way into offices and a conference centre.

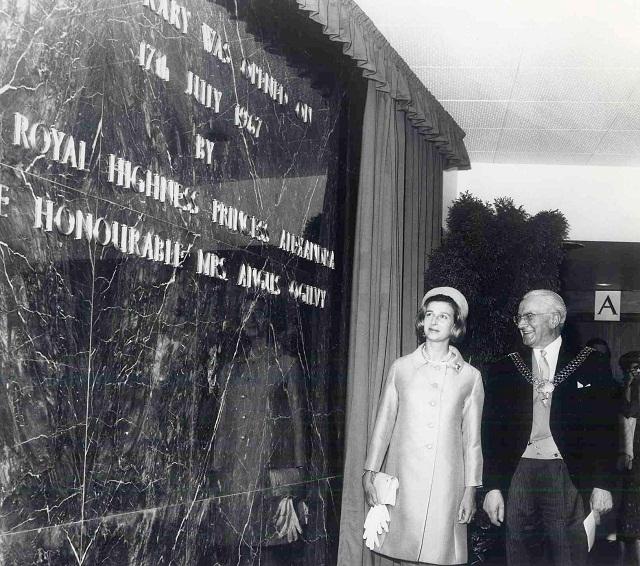

When the building was formally opened by Princess Alexandra 46 years ago, the cost was put at £800,000. Since then, the currency was decimalised, Britain joined the European Community, and monetary values changed greatly.

In 1967, the sum of £8m would have bought you a professional football club, probably several clubs, whereas today it wouldn’t cover the cost of Wayne Rooney’s annual wages.

The eight-storey library and its adjacent 400-seat theatre were designed by Bradford Corporation’s City Architect Clifford Brown. Apparently, he worked out his design in consultation with City Librarian Harold Bilton and was the country’s first library based on the subject-department principle.

Two months before his retirement in September 1972, Mr Bilton gave the T&A chapter and verse. When he got the job in 1951, Bradford’s main library was located among shops and offices in Darley Street.

It was there that he decided that the new building should be based on the American idea he had read about of combining lending and reference sections into departments, one for each subject.

“There was no real opposition,” he said. “I was certain in my own mind it was right to break away from tradition and I could not see any point in dividing off a reference library and keeping it as some sort of ‘holy of holies’.

“The best answer would have been to have gone to America to look at some subject department libraries, but that was just not practicable. It means our library was an original design by the City Architect and not a copy of anything.”

Alas, it was also full of asbestos, and in October 2011, the open stairwells were declared a fire risk by health and safety officers. It wasn’t fire that proved a hazard in the early days, but the fire alarm system that had been installed.

Evidently the sensors were hyper-sensitive, for a boiling kettle or a workman’s cigarette smoke – how times change – set them off 12 times up to December 1967, causing the building to be cleared and fire engines from nearby Nelson Street to arrive clanging outside.

The fire brigade’s fire prevention officer, Leslie Roast, told the T&A: “Teething troubles are not uncommon after the installation of detection systems such as this.”

A couple of months before Princess Alexandria performed the official opening, the Central Library opened for business on April 17 at 9am. This was half-an-hour earlier than the days when the library was based on the upper floors of the magnificent Kirkgate Market building – gone now, it was demolished along with the market in 1973.

“The doors opened and there was nobody there. That’s my biggest memory of that day,” said Mrs Geraldine Moorhouse, who now works on the counter at Eccleshill Library.

In the spring of 1967, as Geraldine Hayes, she was a 16-year-old library assistant who had spent a month in the marble and mahogany interior of the Darley Street building before transferring to Clifford Brown’s new building.

Assigned to the popular fiction department on the ground floor, she was on hand to stamp the very first book borrowed, a Western entitled Riding For A Fall. It was taken out by Mrs Katherine Halliday. Asked what she thought of the new building, she said: “It’s lovely.”

Demolition and construction work were still going on on sites nearby when the Central Library opened. Mrs Moorhouse recalls a spooky incident: “The church where the law courts now stand was still there. When we started, you could see them taking the bodies out of the graves before they built the law courts,” she added.

The Central Library was one of many significant landmark developments in Stanley Wardley’s grand design for modern Bradford. Bradford Corporation’s City Engineer planned to have built a community theatre and a new, large concert hall.

The latter was never built, but the Library Theatre had a bar and lounge area and proved popular with local theatre groups such as Buttershaw St Paul’s Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society.

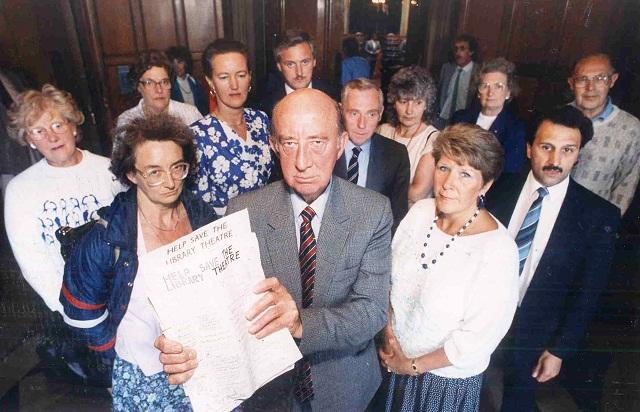

They were among the campaigners who tried to save the theatre being subsumed by the National Photography, Film and Television Museum next door. They failed. The Library Theatre is now the Pictureville Cinema.

In August 1992, a report to the Council’s community and leisure sub-committee described the building as a deteriorating health hazard that required at least £150,000 spending on it to make it safe again. The air conditioning had stopped functioning in 1989 which led to staff working in temperatures of more than 100F in the summer – again, how times change.

Perhaps if extensive remedial work had been carried out on Clifford Brown’s state-of-the-art Central Library a lot sooner, the building would not be in the state it’s in now.

In spite of the state of the building, stirling work went on inside. In the 1990s, literary festivals were staged there. The late Keith Waterhouse, Daily Mirror and Daily Mail columnist and co-author of novels and plays such as Billy Liar and Budgie, was interviewed in there. Bradford’s Poet Laurate Gerard Benson gave talks there on great poets.

In 2001, when Bradford was an aspiring City of European Culture, senior librarian Robert Walters was one of the judging panel that took the innovative step of giving a three-month residency to Bradford’s Redbeck Press, a small publisher of poetry and prose run by the late David Tipton.

Bradford’s literary officer at the time was Tom Palmer, now a successful children’s writer. He said of the Redbeck residency: “As far as we know, this is unique. I think it’s really significant for the library and a publisher to work together to promote reading and writing. I think the idea will be copied across the country.”

Enterprisingly, the library also published local history books such as the late Geoff Mellor’s Movie Makers And Picture Palaces and East Bowling History Workshop’s pamphlet Bowling Tidings.

Inexplicably, this activity was stopped eight or nine years ago following a management shake-up at City Hall. The two Central Library men who had masterminded the publishing arm, John Triffitt and Bob Duckworth, both retired. A sad loss to the proliferation of local culture.

To some, it would be most ironic if the Odeon, built and opened in 1930, were to survive and the Central Library, opened in 1967, were to go the way of other civic improvements from the 1960s and 1970s – Central House, the Transport Interchange’s vast glass roof and all of the brave new world buildings put up in Forster Square.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article