Maths lessons filled me with dread.

I remember tears pricking my eyes as I sat and stared at the page, desperately trying but unable to fathom the concept of tens and units.

‘Carrying one over’ caused me no end of trauma. I couldn’t make it work and I tested my mum’s patience as she tried in vain to get me to understand how to do it. Thirty years later, talking to retired primary teacher, Celia Stone, I’m beginning to think my failure to grasp basic mathematical skills could be something more than just not getting it.

I’d heard of dyslexia, but words weren’t a problem. Maths was though. Dyscalculia is a condition experts came up with, following extensive research into why some people can’t grasp numbers, Celia, who is familiar with research carried out by Professor Brian Butterworth, a leading authority and author of The Mathematical Mind, says there is an area in the brain which processes numbers. In her book Dyslexics Or Dyscalculics, Celia explains that area of the brain isn’t functioning as it should.

“It doesn’t matter how old people are, numbers do not have the correct meaning for them. The question for the educator is, how do we try to get that meaning in?” she asks. “The only way is by multi-sensory teaching. Babies touch things and bite things – that is how they explore the world. That is how the brain naturally learns.

“Research suggests that there’s a specific part of the brain that recognises and deals with numbers. What I have speculated, which I think is true, is that some people with dyslexic problems seem to find these dyslexic difficulties also impact on their abilities to learn numbers.”

Celia specialised in the teaching of dyslexics in her native Zimbabwe. When she and husband Bryan came to Britain 28 years ago, she recalls people hardly dared say the word dyslexic.

In 1981, Celia, whose daughter and grandson are dyslexic, set up a dyslexic unit at Woodhouse Grove School in Apperley Bridge. Bryan taught French there and became house master and head of modern languages. Celia ran the unit for ten years and also ran a unit at Bronte House School.

In the 1990s, she collaborated with her co-author, Myra Nicholson, on a series of ‘Beat Dyslexia’ activity packs, which have been published in America and are widely used by learning support services.

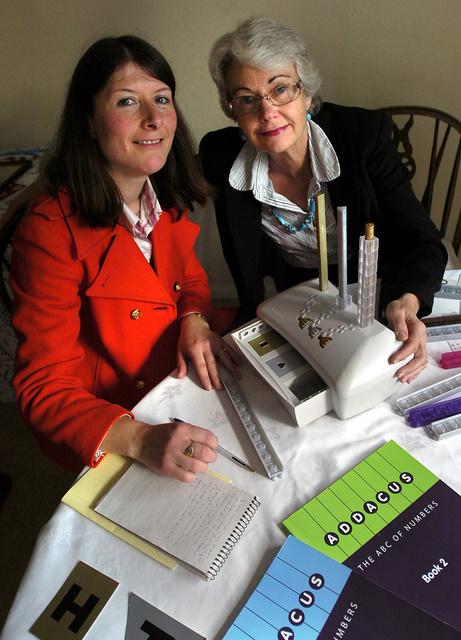

Addacus was born out of Celia’s passion to help people with learning difficulties. She developed the teaching aid, based on the abacus concept, while attempting to write a multi-sensory workbook on numeracy.

Researched, tested and modified by the Centre for Design and Research at Northumbria University, the equipment is designed to teach and reinforce basic number concepts through a hands-on discovery method, developing understanding of the vocabulary and language of maths.

Games, songs and practical activities, combined with a rainbow of coloured equipment, help to remove the fear of numbers.

The purpose of Addacus, used in more than 400 schools throughout the UK, is to teach ‘place value’. Gold, silver and bronze posts are indicative of the colours of money. Cubes have a core shape – rectangular, oval and triangular – to fit the appropriate post.

Each post only accommodates nine cubes, so pupils learn place value by operating the ‘calculator’ themselves.

Sitting down at the equipment with Celia I know I won’t be able to do it before I try. Celia sets me a test; putting two cubes on the Tens post makes 20, and nine cubes on the Units makes 29. I move the dials below the relevant posts to illustrate the number two and nine. So far so good.

Celia asks me to take four away, leaving me with 25. She then asks me what happens if I take seven away.

The dreaded ‘carrying over’ sequence resurrects the insecurities I had with maths in my schooldays.

Hesitantly I take one of the ‘Ten’ cubes off the post and drop it into the drawer below. Then I take ten Unit cubes from the drawer and place them on the separate number strip. Taking seven away leaves me with three, which I then put back on my Units post. Adding them to the five already on there, I have eight. The one cube left on my Tens post brings me to the answer – 18!

I’m usually fuddled by figures but, at last, light dawns!

Celia and Bryan are promoting Addacus themselves from their Guiseley home. Celia is aware of the demand for educating youngsters with learning difficulties and she knows Addacus can help, judging by the feedback the couple have received. “One little boy used to go and put his head on the desk. After they did this, he was willing to answer questions,” she says.

The system is devised with parents in mind so it can be used at home as well as in schools.

“It’s important to understand that having dyslexia in no way makes you a less intelligent person, but our way of learning is particularly difficult for dyslexics,” says Celia. “Somebody once said to me when I was training, ‘If they can’t learn the way you teach, can you teach the way they learn?’ “That is what I am trying to do.”

- For more information, visit addacus.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article