Here, Robin Longbottom examines how what was little more than a length of string played a vital part in powering textile machinery

UNTIL the 1950s and 1960s, on Bonfire Night fathers would often bring home short lengths of old, oily, mill band from the mill.

When lit at one end it would glow in the dark and children would swing it around and make patterns. It was also used to light fireworks.

The origins of mill band date back to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution when Richard Arkwright’s complex water spinning frame was largely superseded by a much simpler one developed from James Hargreaves’ spinning jenny.

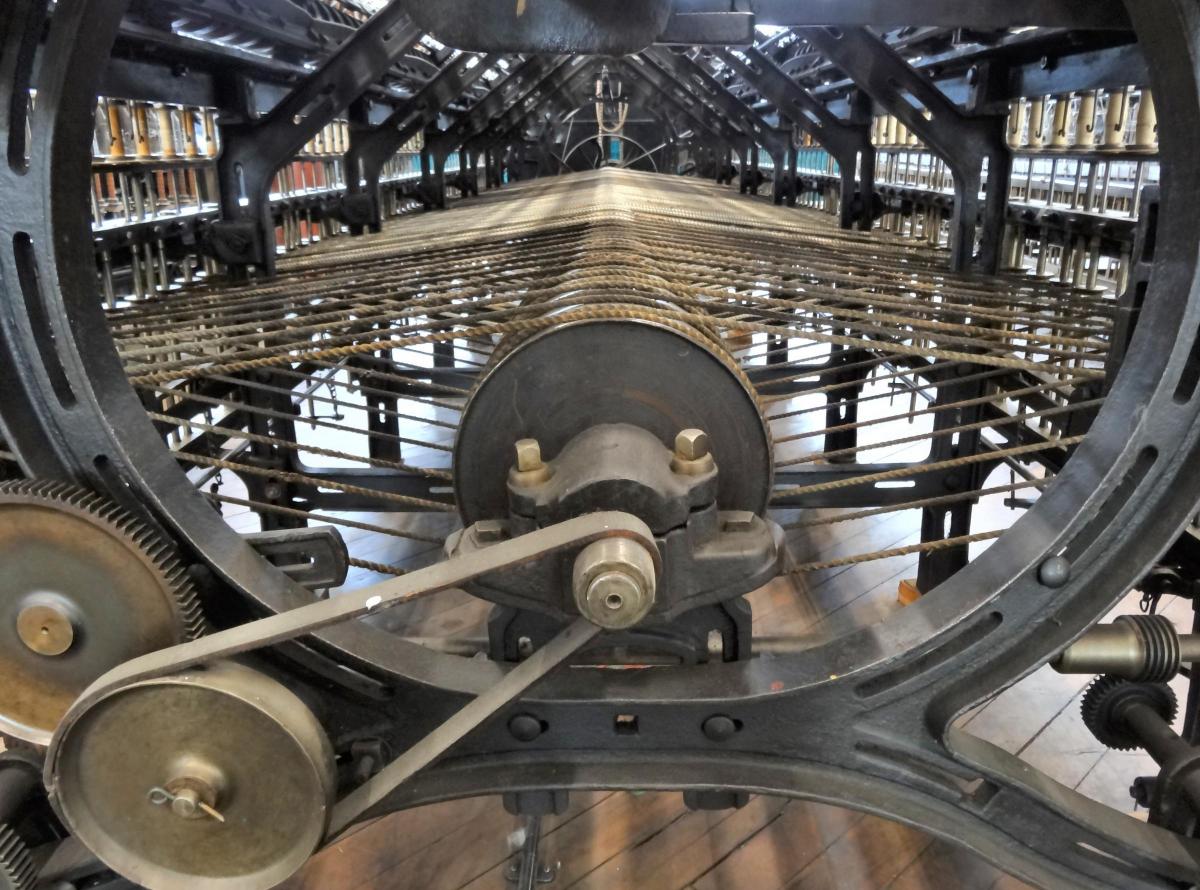

The jenny used a tin roller to drive multiple spindles on the machine as opposed to Arkwright’s complex use of gears and pulleys to drive the spindles.

Although the jenny was a hand-powered machine the principle of the tin roller was quickly adopted for use on water-powered machines.

The transmission of power from the tin roller to the spindle is where the mill band came in. Little more than a length of string, it was not much thicker than the average pencil and went around a mechanised roller and from there turned the spindle which spun the yarn. Multiple spindles could be run from a single tin roller.

The northern word ‘band’ has Old Norse origins and is little used today, other than in words such as rubber band and baler band (used to bind-up hay and straw bales).

Well into the 1960s and early 1970s mill band was still being used to power the spindles on both worsted and cotton spinning frames.

Mill band was made by twisting three long lengths of cotton fibre together. Tightly twisted cotton cord was preferred because it did not stretch like hemp or jute and it was extremely durable.

The process of manufacture had originally been very laborious and involved running the lengths of hemp or cotton out along a rope walk, a hundred yards or more long. The lengths were twisted together from one end and as they tightened were drawn-up on a movable carriage. The rope walk in Keighley was along St Andrew’s churchyard wall between the beckside and the church gate on Market Street.

During the early 1800s machinery was developed to replace the rope walk but Keighley does not appear to have had its own manufacturer of mill band until a mechanic called John Midgley began production in the 1850s.

John Midgley had served an apprenticeship as a machine maker and mechanic in the 1820s, but having been unsuccessful in establishing himself making textile machines, he eventually saw a business opportunity making mill band.

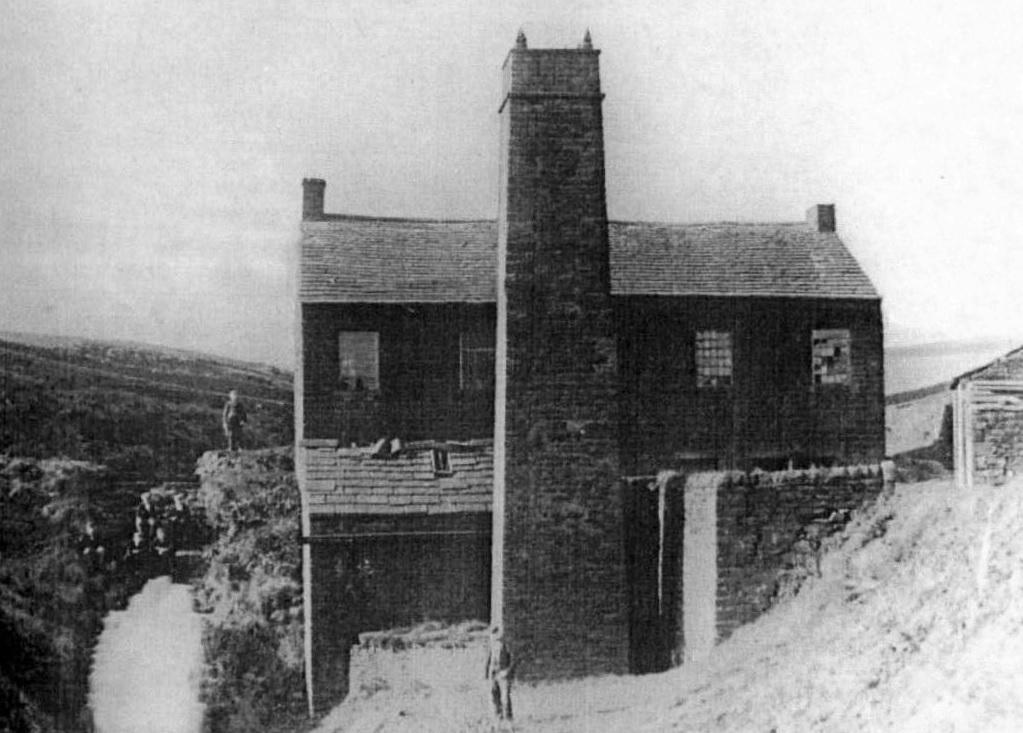

By the late 1850s he had moved from Keighley to Newsholme, near Oakworth, and taken a lease on High Mill, which had been formerly used to make bobbins.

Here he established himself as a spindle band maker, manufacturing the band with machinery powered by a small mill engine.

It was very much a family business – he employed his two sons, Joseph and Thomas, and his daughter Martha.

When trade was slack, he supplemented his income farming a smallholding of 14 acres and working occasionally as a mechanic at local mills.

Despite advertising his product in local and national business directories he was eventually unable to compete with the bigger manufacturers and in the 1880s the family business closed down.

The mill was then used as an agricultural building and has since been converted into a house.

Today with our world of space-age technology it is difficult to imagine that for nearly 200 years a whole industry was dependent upon little more than a thick piece of string.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here