RESEARCHERS are close to discovering more about the lost world that lays deep beneath the North Sea thanks to work being carried out by Bradford University.

The team at the university is part of multi-institution effort to map Doggerland – a vast area once connecting Britain to North West Europe, once brimming with plants, wildlife and humans, and which was submerged after the last Ice Age.

Now ships have been sent into the zone to drill core samples in the sea bed in a £2.5m EU funded project called Europe’s Lost Frontiers which will yield vital DNA and pollen data allowing a 3D picture to be created of the world now under the sea.

The latest developments in this ambitious project will be revealed at a conference today at York St John College, staged by PLACE, a charity promoting Yorkshire’s natural and cultural heritage and showcasing the latest academic research to the public.

Scientists hope to retrieve nearly a kilometre of samples from selected locations based on mapping which used seismic data donated by the oil and gas industry.

Professor Vince Gaffney, from Bradford University, explained: “Thanks to the initial mapping project developed here in Yorkshire we know a great deal about this lost land.

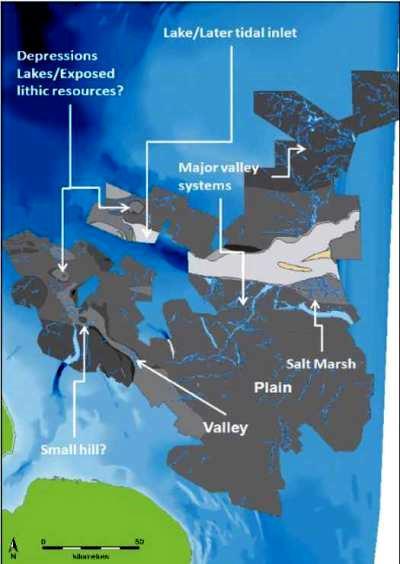

“We have identified 20 major estuaries, countless rivers, and a 300 square kilometre salt marsh, all in an area bigger than Holland.

“This was not so much a land bridge as a rich environment in itself, perfect for a hunter-gathering existence. But what we want to do is discover what grew here, what did the landscape actually look like and are there clues about human habitation?”

Doggerland was first identified as a lost landscape over a century ago, with trawlers occasionally netting archaeological remains, including a woolly mammoth skull.

So far 80 core samples have been collected with the project set to continue for another three years.

One piece of technology used is a Digital Sandpit allows archaeologists at Bradford University to create their own 3D environments, onto which are projected vegetation, animals and humans, whose movements and actions are run by a computer algorithm.

Although other similar bits of kit exist at other institutions, the Bradford team is one of the few to use it in this way.

The computer programme means archaeologists can develop physical environments to visualise the impact of complex equations, and it was on show at a recent open day to inspire future students.

The York conference is being organised with the Royal Geographical Society. Other speakers will reflect on wind turbines and solar farms, the effect of climate change on the moors of Ecuador and our nostalgia for vanished landscapes.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel