Babies are still dying in 21st century Bradford because they are being born into poverty, a two-year study has found.

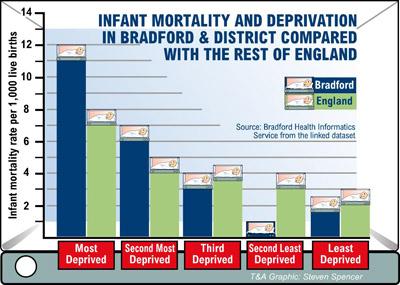

Pockets of extreme deprivation have been pinpointed as the biggest single cause of the district's baby death rate - which stands at almost twice the national average.

The conclusion is reached in the final report by the Bradford District Infant Mortality Commission, a multi-agency partnership set up two years ago by Bradford Vision, to find out why baby death rates are so high.

During the course of its work, the Commission has carried out the UK's biggest investigation into the reasons why babies die in their first year of life, including taking evidence from three bereaved mothers.

It today published its final report giving ten recommendations for the coming years to help parents, health professionals and other service providers reduce the tragic toll of babies dying before their first birthday.

The Commission found factors directly linked to poverty, such as poor housing, education and employment, had the biggest impact on the health of babies.

Babies under one in the most deprived wards - Bradford Moor, City, Toller and Manningham - are five times more likely to die than those in the least deprived wards of Craven, Ilkley, Wharfedale, Baildon, Bingley and Worth Valley.

The report concludes if all babies born into the most deprived 20 per cent of neighbourhoods did as well as those born in the 20 per cent most affluent then the number of babies dying in the Bradford district would drop by 78 per cent. The report emphasises that 99 per cent of the 8,000 babies born alive in the district each year survive and live beyond their first year.

However, between 60 and 70 babies born in Bradford die before the age of one each year - more than 20 above the national average.

Elaine Appelbee, Bradford Vision chief executive, said the report would be used to pave the way for more work to save babies' lives.

She said an action plan to respond to each of the ten recommendations would be put together by a special implementation group set up by Bradford Vision and the group would report on its progress every year.

She said: "The death of any baby is a tragedy for the family concerned.

"Through this investigation, we believe that we have identified the causes of infant deaths and with the support of local people, especially expectant mothers and couples keen to start a family, we are determined to reduce levels of infant mortality.

"All of us in the district now face a major challenge - to look in detail at the report's findings and ask ourselves what more we can do.

"This applies to everyone including parents, the Council, the health service, voluntary groups, employers and many others."

Dr Liz Kernohan, a consultant in public health in Bradford who served on the Commission said: "Losing a baby in the first year of life is a cause of terrible sadness, but it remains a rare event in the Bradford district.

"Huge improvements have been made over many years in local maternity services, both in primary care - such as GP surgeries and community services, and within hospitals.

"The quality of those services is the equal of any in the country. However, we must remain determined to reduce infant mortality and the Commission's valuable work provides new impetus to pursue this."

Bradford mother Cheryl Moorhouse, whose son Joshua had a genetic disorder and died at birth six years ago, was part of the Commission.

She said: "Losing a baby is the worst thing that could happen to any parent. I just hope the Commission's work will help us all reduce the risk of parents losing their babies in the future."

Study shows ten key actions to cut baby deaths

A two-year study of Bradford's high infant mortality was the biggest research of its kind in the country.

The study was commissioned by Bradford Vision, the district's strategic partnership of public, private and voluntary sector organisations.

The Bradford District Infant Mortality Commission was formed and included representatives of Bradford Council, the district's NHS primary care and hospital trusts.

The Commission was chaired by Yorkshire lawyer Julia O'Hara, and took evidence from leading health professionals and university professors and local people, including three bereaved mothers.

It looked at the two communities in Bradford district that are large enough to compare statistically - the white population and the Pakistani-origin population.

Its findings include:

- Throughout its history, regardless of its population mix, Bradford has had consistently higher than average numbers of infant deaths

- For all mothers, social and economic status is strongly associated with the infant mortality rate

- Poverty does not tell the whole story: in both white and Pakistani populations, tackling very low birth weight would reduce the number of infant deaths

- Different factors can affect different groups. In the white population, premature birth, teenage motherhood, smoking, alcohol and drug use are greater risk factors than for families of Pakistani origin. Poverty is a bigger factor in Pakistani populations (88 per cent of Pakistani-origin babies and 41 per cent of white babies are born into the most deprived two-fifths of neighbourhoods). Genetic conditions are factors in both populations, but are more prevalent in families of Pakistani origins.

These include further work to tackle the social conditions which adversely affect the health of locally-born infants.

In relation to the impact of deprivation on baby deaths, action areas are:

- Reducing poverty and unemployment, paying particular attention to levels of educational attainment and increasing opportunities for meaningful employment

- Improving housing and the social environment, with due consideration being given to funding a Housing for a Healthier Baby programme

- Improving the nutrition of mothers and babies

- Ensuring access to appropriate health care, such as the immunisation programme for babies and ensuring support for parents.

- Reducing the number of women who smoke or have high levels of use of alcohol and drugs in pregnancy

- Developing a better understanding of the impact of genetics and strategies for empowering families to deal with genetic risk and ensuring these recommendations are shared widely and understood.

The report fully backs work already being undertaken to narrow the gap between the most deprived communities and the rest.

Dr Sam Oddie, a consultant neonatologist in the neonatal unit at Bradford Royal Infirmary and a Commission member said: "Deprived families are much more likely than rich ones to experience risk factors known to be strongly linked with infant mortality.

"Poorer people are more likely to smoke, have poor diets, not attend for screening and antenatal care appointments and bottle feed, rather than breastfeed their infants.

"As well as having poor housing and lower educational attainment, poorer families may not use car seats which reduce the risks of death in road traffic accidents, miss immunisation appointments and bring ill children later in the course of severe illnesses."

The Commission's summary report was published today. The full findings and evidence are available at www.bdimc.bradford.nhs.uk

- Click here to see Our View

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article