IT had been a long, exhausting journey for Rudi Leavor and his family from Berlin to Bradford.

Rudi was 11 when he and his parents and sister fled Nazi Germany. Travelling to England on a German cruise liner, they arrived on November 11, 1937. “Prior to our escape my parents had travelled to England, trying to obtain entry visas. Only after these were acquired was my father permitted to work,” says Rudi. “He was advised he could work anywhere except London and Manchester where there were ‘too many refugee dentists’. When my father asked: ‘Where can I work?’ the clerk metaphorically stuck a pin in a map and suggested Bradford.”

Rudi’s father took a train to Bradford and paid a deposit on a house in Shipley. But when the family arrived there they discovered the occupants still in residence, “forcing us to spend a week in a residential hotel, eating up precious money”.

“Eventually we moved into our new home. Our furniture arrived in wooden boxes.”

Read our first instalment of Rudi's memoirs here

Rudi’s father, Hans, had just qualified as a doctor when he was enlisted into the German army at the start of the First World War. He received the Iron Cross 2nd class for bravery. After the war he studied dentistry and settled in Berlin, with his dental practice in the family’s flat. Rudi went to Bradford Grammar then followed his father in dentistry, studying at Leeds University.

Says Rudi: “I received my call-up papers for National Service and was able to enrol as a dentist. After a year I was transferred to Austria, travelling by a special troop train called Medloc. Whilst it was in Munich station, the train standing on the neighbouring track had its destination sign right opposite my window - it said Dachau. This was the first time I had come face-to-face with the name of a concentration camp,” says Rudi. “It was 1954 and the horrors of the Holocaust, for whatever reason, were rarely discussed and knowledge about it was scant. The sight of this destination plate was more disturbing than I can describe. I became disorientated. In that train I could see people reading the paper, talking about everyday matters. Did they not appreciate that the track they were on had taken people to death camps? I was glad when Medloc pulled out of the station and that dreaded word was out of sight.”

It was the first time Rudi had been back to Germany since escaping as a child. He has returned many times since but, he says: “My sister won’t go back, and my parents never did”.

As a child in Berlin, he felt the chill of anti-semitism and recalls the day forms were distributed at his primary school with spaces for a family tree. “A short sentence on said Adolf Hitler wished this information to be provided. Under each entry was a space to indicate religion. This was obviously for the state to establish any Jewish blood in the family. My father filled the form in and I handed it to the teacher. It benefited the authorities to be have a family tree bearing information as far back as great-grandparents.”

Rudi felt safer moving to a Jewish secondary school, where he learned English - “which was to become most useful”.

He returned there years later: “After the war my old school building was located in the Russian zone of Berlin, following the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 the Jewish community was encouraged to re-open it as a Jewish school. The original piano, a Steinway, was still in situ but in a deplorable state. Steinway was instructed to renovate it and I was invited to the opening. I performed Das Heidenröslein by Schubert with words by (the Jewish) Heine. It was a very emotional moment.”

Returning from National Service, Rudi joined Bradford Reform Synagogue. “My parents joined, I was expected to follow suit but wasn’t happy about it. At Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) my parents went to the reform synagogue but I said I’d go to the orthodox one. They felt the family should stick together and I should go with them. All the way to the synagogues, which were on either side of the road a few hundred metres apart, I knew that by the time we reached them I would have to decide. I was in turmoil. I hesitated right up to the last second and decided to join my parents.”

Now 94, Rudi is chairman of Bradford Synagogue. It is where he discovered his love of singing: “One of the members formed a choir which I joined. None of us had sung in a choir before. With weekly rehearsals it flourished and I was invited to sing solos.”

Rudi became a member of the Leeds Philharmonic Choir for 50 years, performing at venues such as the Royal Albert Hall.

“I took over the synagogue conductor’s baton, but over the years the choir numbers dwindled as one member after another disappeared. Now I am the choir, the sole representative, singing everything solo,” he says. “Each year I sing the Hebrew mourning prayer, El Male Rachamim, at Holocaust Memorial Day events in Bradford and other places. In 2003 I joined the Holocaust Survivors’ Friendship Association, a talk was given by a lady who was born in a concentration camp in Lithuania. As a child she asked her mother: ‘Why don’t Jewish children have grandparents?’ I was very moved by this seemingly innocent remark. The Association extended into education, with members giving talks to schools. The Holocaust Learning Centre was set up at Huddersfield University in 2018. My small contribution is a recording of the Hebrew mourning prayer, El Male Rachamim, preceded by Brahms’ Lullaby, played in the museum.”

One rainy evening in November 2012, there was a knock at Rudi’s door: “A Muslim chap started talking about an application to open a restaurant near his restaurant, and near the synagogue. He had papers appealing against it and wanted my help. I agreed and represented us at City Hall. It was the beginning of a close relationship between Dr Zulfi Ali and myself.

“Subsequently I forged close links and friendships with the Muslim community who supported our synagogue in many ways.”

In 2012, with the future of the synagogue in doubt, the local Muslim community, through Carlisle Business Centre, donated £500 to repair and save the building. It made headlines around the world. “We thought we might have to sell the building,” says Rudi, who went on to establish interfaith relationships with Bradford’s Cathedral, churches and Hindu communities. The synagogue is the only one in the world with a Muslim member, Jani Rashid, on its Council.

Over the years Rudi has worked tirelessly to keep the synagogue going and in 2017 he was awarded the British Empire Medal for his interfaith work - one of several awards he has received.

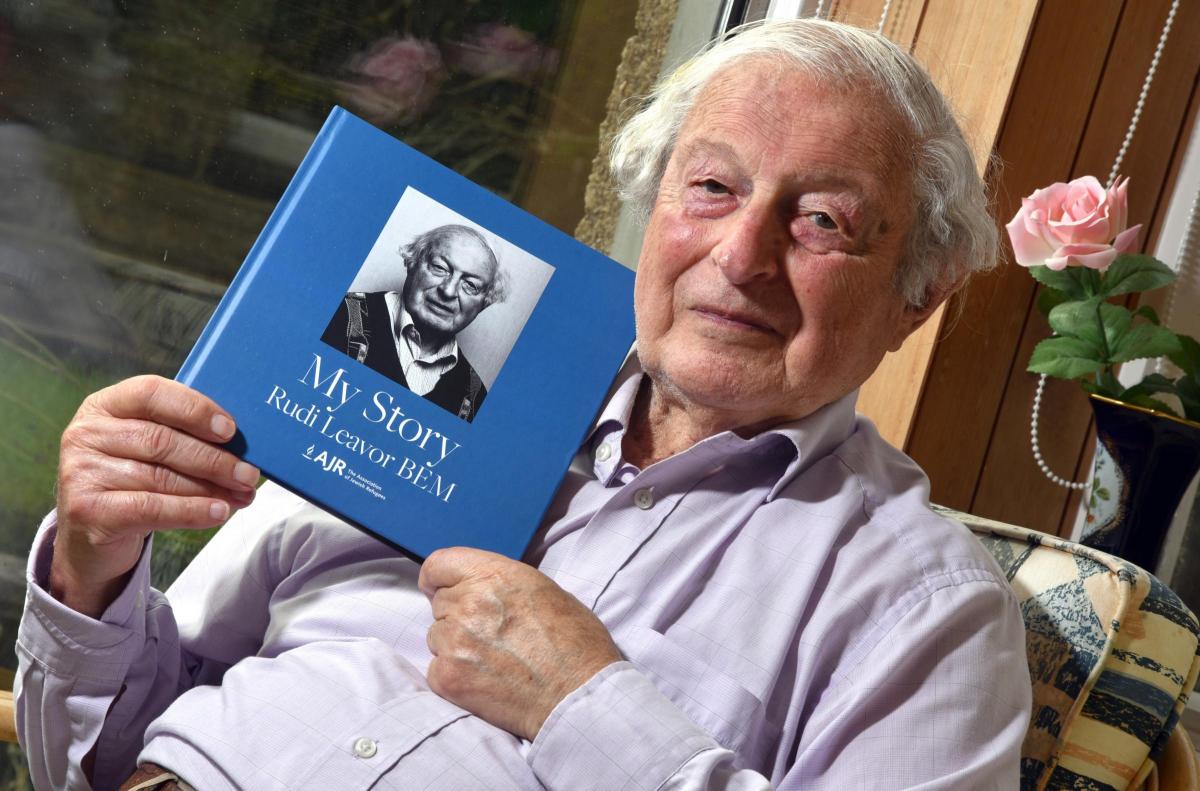

He reflects on his life in Bradford, his childhood in Berlin, and family life with his late wife Marianne and their four children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren in his fascinating memoir, My Story. This abridged version, to be followed by a full version, is published by the Association of Jewish Refugees, which supports Holocaust refugees and survivors in Britain.

* Visit ajr.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel