RUDI Leavor arrived at his Berlin primary school one day to find a diamond-shaped board on the teacher’s desk, with sections coloured red, white and black.

Each boy was told to choose from boxes of nails with heads in the same three colours and hammer them into the matching fields. Once all the nails were in, a black swastika emerged on a white background surrounded by red.

“When it came to us Jewish boys, the teacher said we three did not have to do this. I think she was being kind,” says Rudi, who was born in Germany in 1926.

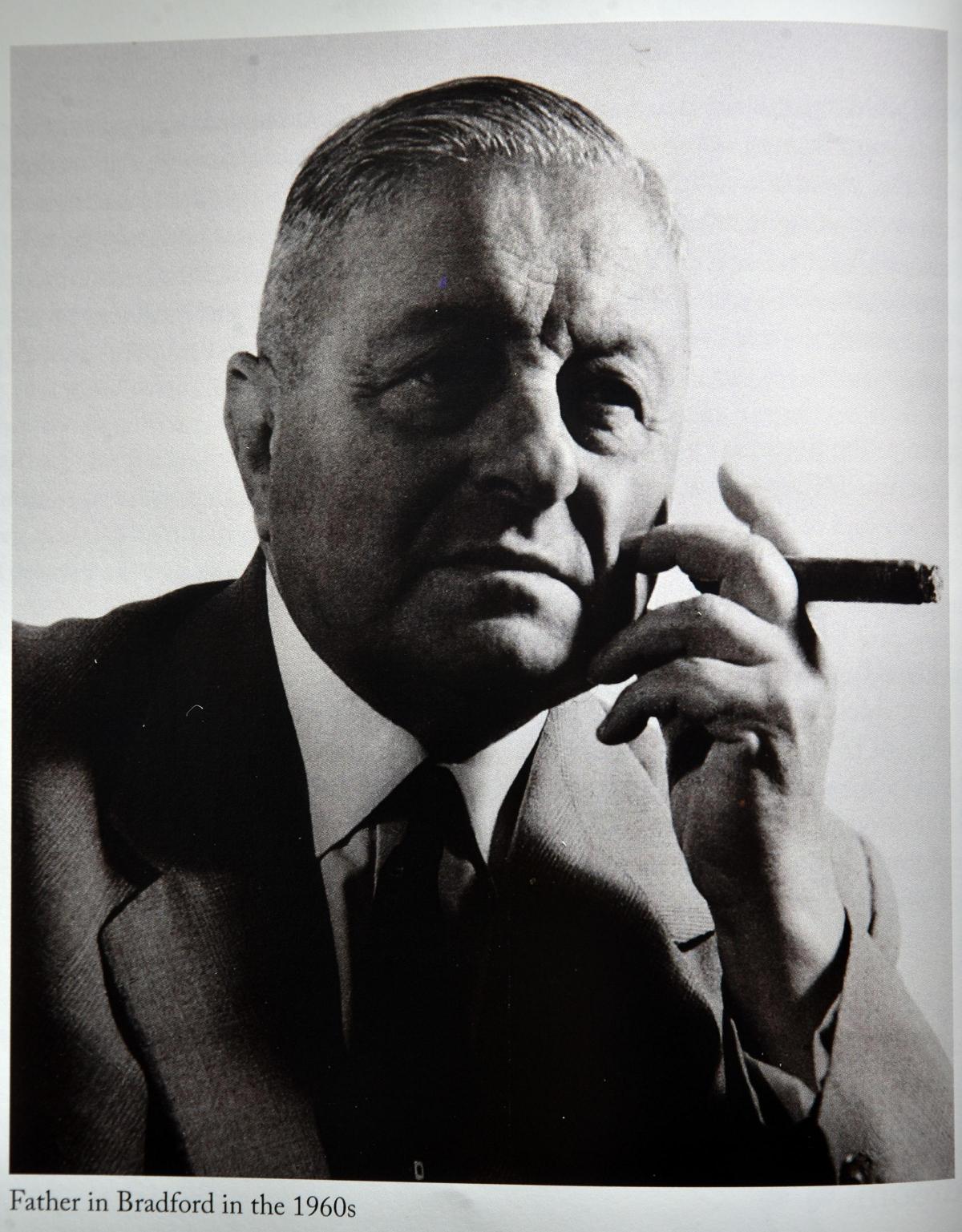

Later in his childhood, after SA troops marched near his family’s home - “A terrifying sight,” he recalls - his grandfather and great aunts came for coffee and cake. “My father was nervous; he kept going round the table and eventually he whispered in my ear: ‘We are going to England’,” says Rudi. “Three thoughts went through my mind: We’re escaping anti-Semitism. We’re leaving relatives behind. We will be travelling on a train - something I liked.”

It was an early morning visit from the Gestapo in 1936 that led to the family’s escape. Rudi vividly recalls two men barging in and arresting his parents: “I said ‘Good Morning’ and offered my hand, which they shook. They told my parents to get dressed and join them in their car.”

Later released, his parents managed to obtain visas for Britain. “They saw it as a warning. Without their arrest, we might not have escaped the fate of millions of Jews in the gas chambers and ovens of Auschwitz,” says Rudi.

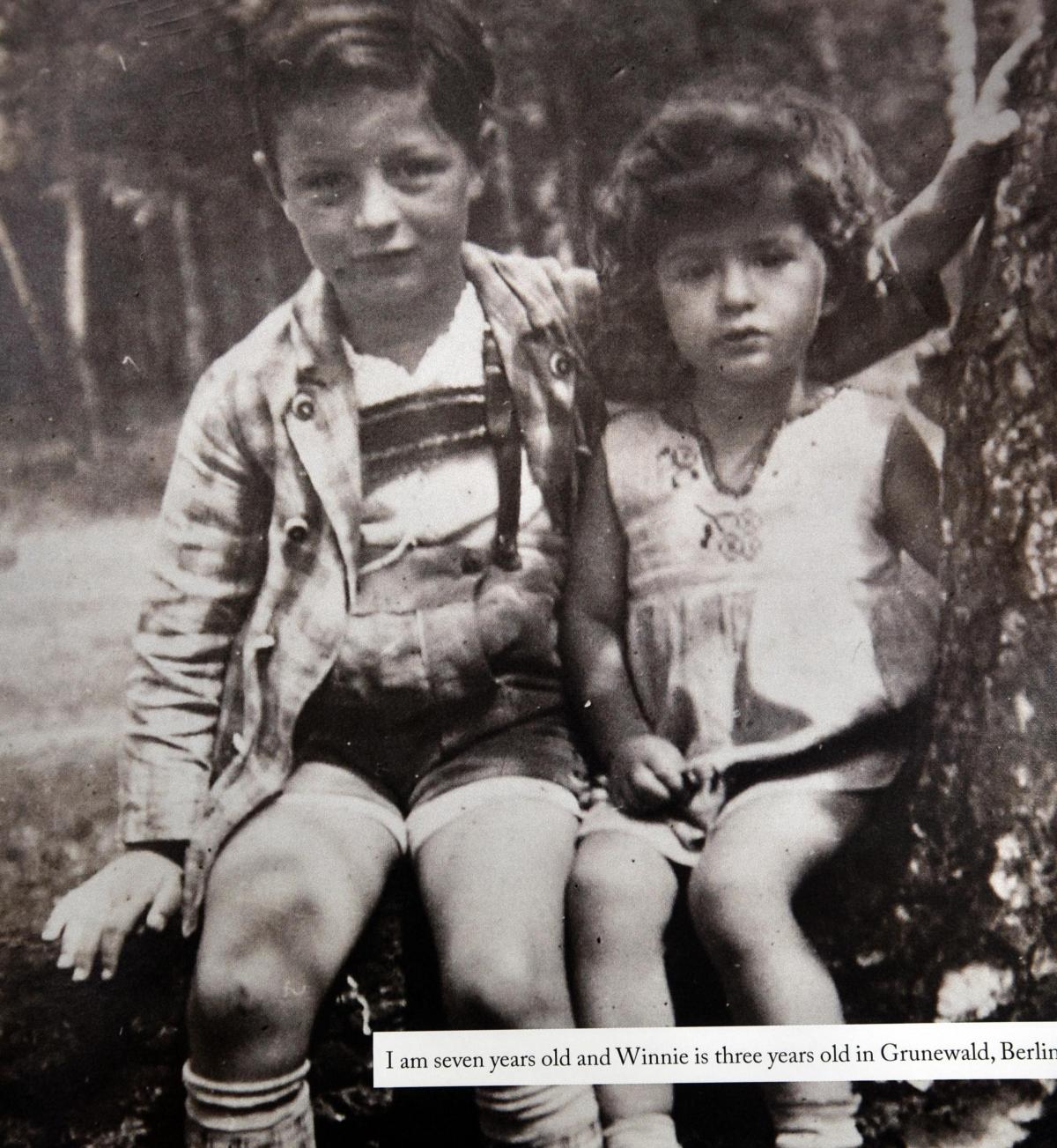

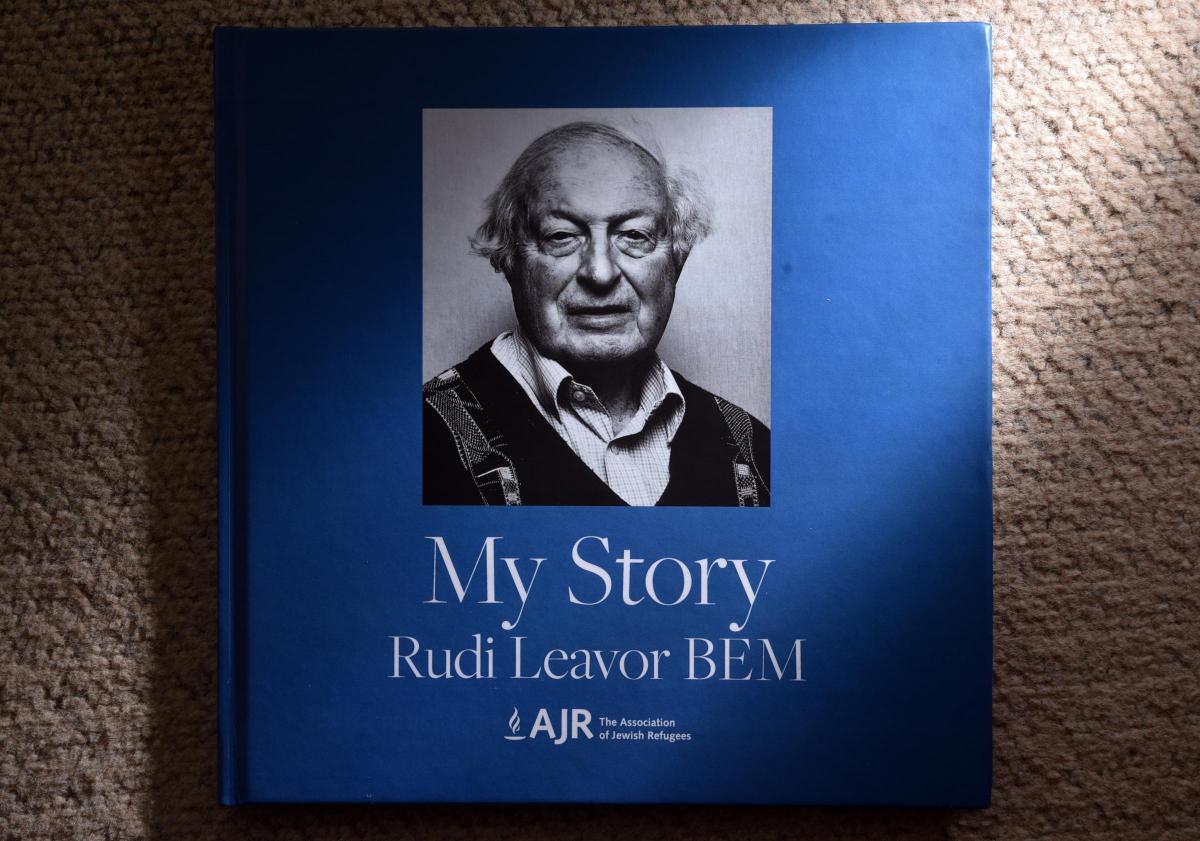

The following year, aged 11, Rudi left Germany with his parents and sister, Winnie. After a long, frightening, exhausting journey the family settled in Bradford. Today Rudi is 94, chairman of Bradford Synagogue and internationally renowned for his community work. His remarkable life story unfolds in a memoir which he may never have written were it not for a chance encounter in a Tenerife timeshare. “I stayed in the complex every January and saw the same people there. It turned out one of them worked for the BBC, one day she said ‘Tell me about yourself’. So I did and she said ‘I hope you’ve written all this down’. I was 92 and thought I wouldn’t have time to finish it. She said: ‘Go home and do it!’

“It is mainly for my children,” adds Rudi who, with his late wife Marianne, has four children, eight children and now two great grand children.

The anti-Semitism he came to know as a child in Berlin “started little by little”, he says. “It was stirred up by newspapers and the radio.” He remembers like it was yesterday stopping to say hello to a schoolfriend in the street. The boy suddenly slapped Rudi’s face. “Retaliation was not on my agenda and I went on my way. The slap hurt, but more distressing was that a classmate with whom I had a good relationship should hit me,” says Rudi. “Many years later I thought about what precipitated it - the media encouraging anti-Semitism, his parents discussing it at home...”

More sinister was the large sign Rudi came across arriving at an open-air swimming pool: ‘Hunde Und Juden Unerwünscht’ (Dogs and Jews Unwelcome). “I was struck by the word ‘Dogs’ before ‘Jews’,” he says.

On the night of November 9, 1937, the family left Berlin by train. Midway through the journey a customs officer, checking their papers, told his father to accompany him to another compartment. “The train stopped at a station and when it began to move again my father was not back. My mother was anxious but he came back, saying the official had merely examined him for contraband,” says Rudi. “In Bremerhaven we boarded a cruise liner bound for America, calling at Southampton where we were to disembark. Wearily we stumbled along the gangway. Still in Germany, anything could happen and our nerves were in shreds. As we entered the dining-room a band struck up: Dornröschens Brautfahrt. My father and I often played the piano ‘four hands’ together and this was our favourite piece. We’d played it endlessly. Of all the thousands of pieces of music, this was what greeted us on that boat. Music from heaven.”

Rudi’s love of music began as a child when he was given a musical box. A music teacher at his Berlin school, Alfred Loewy, was a major influence. After the war Rudi learned he had been murdered at Auschwitz, along with another teacher, Arnold Amolsky. Says Rudi: “My old school, Bradford Grammar, has an annual speech day when prizes are awarded. I funded an award to promising music students in memory of Loewy and Amolsky.”

The only member of Rudi’s family to survive from Berlin was his great aunt Hulda, rescued from Terezin concentration camp in former Czechoslovakia. “Among the food given to them on the (rescue) train was a rosy apple. In the camp food tended to be hoarded and, although she was hungry, it was a while before Hulda ate it. She lived with us until her death in 1955 and not once did we ask her about the camp. People didn’t talk about it,” says Rudi.

Over the years he has returned to Berlin many times and donated artefacts to the city’s Jewish Museum. In 1978, shocked at the overgrown state of the Jewish cemetery in East Berlin, Rudi formed a committee and wrote to Jewish communities worldwide. Funds came in to restore the cemetery and Rudi managed to trace his ancestors’ graves. “Great-Aunt Etta, who committed suicide when Jews were rounded up, was buried there. Her grave had no headstone because all the family was taken away. I arranged for an engraved stone. When the infamous wall came down in 1989 the Jewish community merged with West Berlin’s more affluent community and took on administration of the cemetery.”

Rudi has been a member of Bradford Synagogue since his early days in the city. “One day the synagogue answer machine picked up a message from a woman seeking a refugee wishing to return to Germany. I contacted her and she said she and a film director were making a film about refugees returning to Berlin,” recalls Rudi. “A few months later, after receiving an invitation for a reunion from my old Jewish school in Berlin, a film crew arrived in Bradford to document aspects of my life then we went to Berlin for the shoot. They recorded in the school, the cemetery and a theatre.”

The film caught the attention of Steven Spielberg, who did further research for his own film and invited Rudi to Los Angeles for the première. “Flight tickets arrived, all expenses paid, and I spent a week as Spielberg’s guest, along with the other seven survivors whose stories were filmed. We were treated like royalty,” says Rudi. “The film was called The Lost Children of Berlin, later shown on television.”

Our next instalment of Rudi’s memoir looks at his life in Bradford, from the family’s arrival, in November 1937, at a house in Shipley, to find it already occupied, to his award-winning work with the Synagogue and neighbouring communities, which has made global headlines.

* Rudi Leavor: My Story is part of the Association of Jewish Refugees’ My Story series. Visit ajr.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel