ONE hundred years ago, Britain and her Allies began the final advance to victory in the First World War. PETER RHODES tells how 10,000 heroic Yorkshiremen helped turn the tide of battle

"On the last day of October 1919 my grandfather, John William Smith, sat down in his joinery shop at Lothersdale near Skipton and began writing his diary of the Great War of 1914-18.

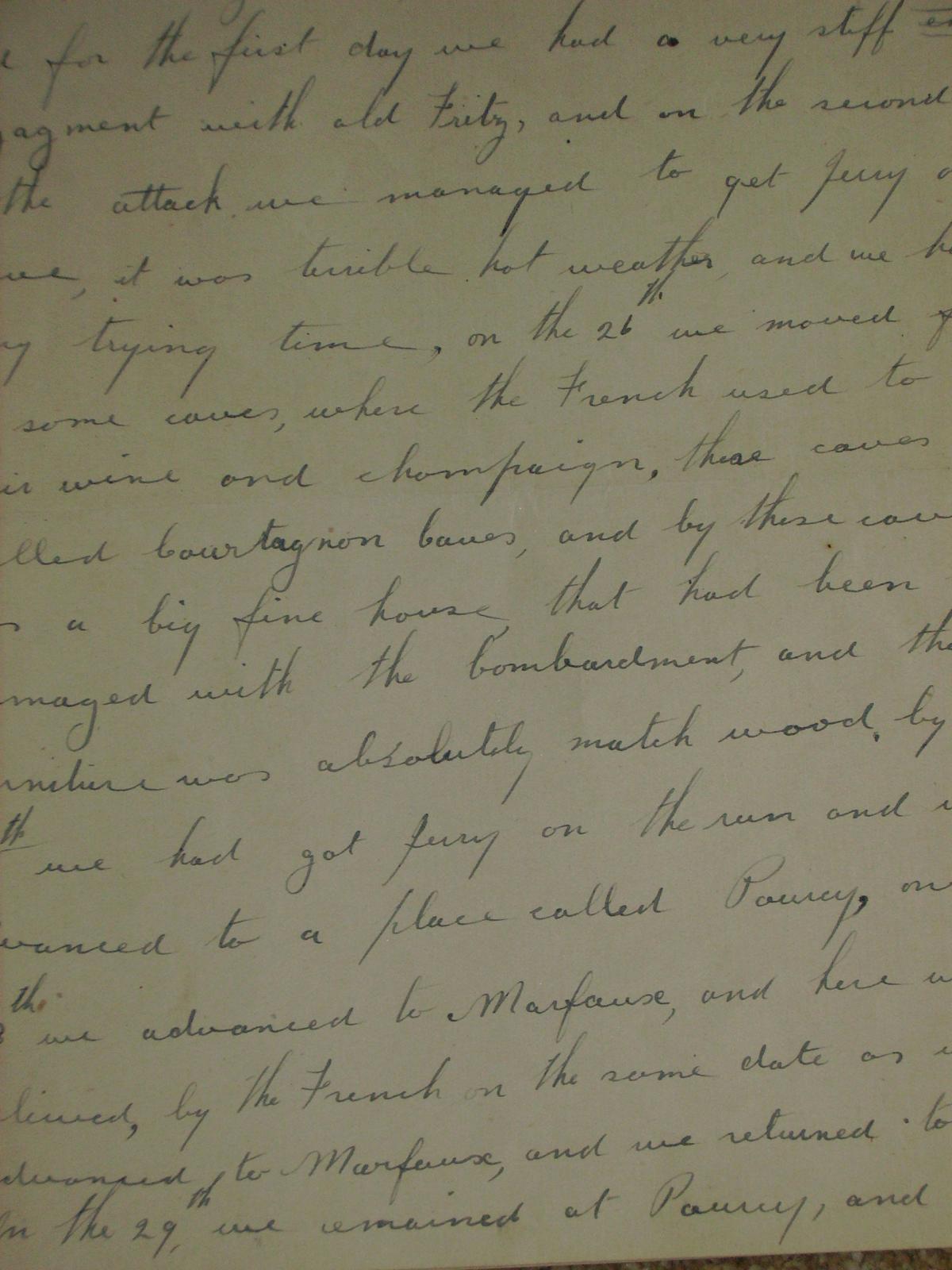

He finished it 23 days later. It runs to 27 sheets of yellowing notepaper. The final pages tell a Tommy's tale of a battle which is today barely remembered but changed the course of the war.

Grandad had signed up aged 19 in the first rush of war fever in 1914 but was assigned to a second-line battalion of the Duke of Wellington's Regiment which wasn't even sent to France until 1917.

In July 1918 he was one of 50,000 Tommies suddenly snatched from the British Army's front line in northern France and loaded on to trains heading south.

As he wrote in his diary: "We left at about 6pm and passed through some lovely country and rumours were spreading like lightning. Some said we were going to Italy and some said we were going to Messop (Mesopotamia) but we landed at Reims. We went through Paris...we could see Eiffel Tower quite plain."

Grandad was describing the build-up to the Second Battle of the Marne. It was chiefly fought by French, American and Italian troops against the advancing Germans and is a battle barely mentioned in British military history.

And yet some Brits were there, rushed to the Champagne country around Reims where the Germans had made their last great attack of the war. Private Smith's regiment was part of the 62nd (West Riding) Division of about 10,000 men.

The Germans struck hard, on July 15. Within four days, the Italian Corps had lost 9,334 officers and men, nearly one-third of its strength.

The Yorkshire division, fighting alongside the Scots of the 51st (Highland) Division, was rushed straight into battle, passing through the shattered Italian ranks. The German attack was halted and reversed.

On July 20 the French commander General Henri Berthelot ordered the counter-attack. As Grandad put it in his diary: "For the first day we had a very stiff engagement with old Fritz and on the second day of the attack we managed to get Jerry on the run. It was terrible hot weather and we had a very trying time.”

Grandad, a signaller, described being attacked by German aircraft: "We had a lively night with Jerry bombing planes and he didn't half make stuff fly."

The Second Battle of the Marne was a turning point of the war. Grandad and his pals fought like lions around the River Marne. The Allies took 29,367 prisoners, 793 guns and 3,000 machine guns and inflicted 168,000 casualties on the Germans. But in the process about a quarter of the soldiers of the 62nd Division were killed, wounded or missing.

General Berthelot was impressed with his Yorkshire warriors. The Croix de Guerre for gallantry was awarded to the 8th West Yorkshire Regiment (Leeds Rifles) for their tenacious attack and the general ordered a ceremonial parade of the West Riding Division and their Highland comrades.

The Tommies were dog-tired and their equipment was filthy. It was time for a little Yorkshire thrift. Realising the general would see only one side of the parade, the soldiers were ordered to clean only where necessary.

As a senior British officer recalled: "An amusing part of the show was that, as there was not time to clean everything thoroughly, the Brigadier had all the brass hubs on the side General Berthelot would stand polished up to the nines, the hubs on the other side remaining in the state that 10 days' continuous fighting had made them."

The fighting took place across vineyards. As Grandad recalled the parade: "The commander stood on the left-hand side of the road and on the other side there was the massed band playing. As we marched past we passed by fields and fields of grapes and if they had been ripe we should have made ourselves badly."

General Berthelot told the Tommies: "Your French comrades will always remember with devotion your splendid gallantry and your perfect fellowship in the fight".

Four months later the British Army was at the gates of Germany. The “war to end wars” was over.

Private John William Smith was not there to see it. He was gassed by a German shell at the end of September 1918 and spent Armistice Day, November 11, temporarily blinded and in hospital. He recovered enough to serve with the British Army of Occupation in Cologne but never regained good health. He died in 1955 aged 60.

His final entry in his diary, describing his demobilisation at Ripon in 1919, reads: "After being in the Army four years and five months, it felt a treat to be a free man once more."

* Peter Rhodes, a former Territorial Army officer, is the author of For a Shilling a Day (Bank House Books), a compilation of more than 200 memories of warfare. It is available from Amazon,

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here