"IN the early 1980s I stayed with my great aunt Lydia and her family in New England. As she showed me the family album her parents had put together for her, when she emigrated in 1923, she paused at the picture of Erasmus Orwin.

She told of her great sadness at the loss of her beloved brother ‘Razzy’ who was killed in the Great War. Years later my research led me to the dusty pages of The Bradford Daily Telegraph where I discovered details of Razzy’s death on February 28, 1917 and that he served with the Machine Gun Corps in Salonika.

Today the port of Salonika is known as Thessalonika, a modern, vibrant city in Macedonian Greece. For centuries it was under the control of the Ottoman Turks whose influence is still much in evidence in the architecture. But from 1915 to 1918 this part of the Balkans became the scene of some of the most bloody battles of the First World War.

In October 1915, a combined Franco-British force of some two large brigades landed at Salonika at the request of the Greek Prime Minister. Their objective was to help the Serbs in their fight against Bulgarian aggression.

However the expedition arrived too late, the Serbs having been beaten before they landed. It was decided to keep the force in place, even though some Greeks, including King Constantine, were pro-German and were opposed to the allied build up.

After the disaster that was Gallipoli, the British had no choice if security for shipping in the Mediterranean was to be maintained and supply lines to British forces involved in the campaign in Palestine were to be protected.

During the first four months of 1916 the British Salonika Force had enough spadework to last it for the rest of its life. Roads were almost non-existent and new ones had to be made.

On top of this a bastion about eight miles north of the city was created. This area became known as the ‘Birdcage’ due to the vast quantity of barbed-wire used.

The Bulgarians and Austrians had also been busy fortifying the heights on the hills surrounding Salonika which would prove disastrous for the allies in the months to come.

At home the campaign was mocked and treated as some kind of side-show. The British press even dubbed our troops in Macedonia ‘The Gardeners of Salonika’ due to them not fighting as many battles as the forces in France and Belgium.

In truth thousands of men died in the harsh terrain, constantly enduring enemy shellfire from the Bulgarians who dominated the high ridges. In winter there was the freezing Vadar winds and in the summer, raging heat filled with malarial mosquitoes.

Before the war Erasmus Orwin was employed by the United States Metallic Packing Company which was based at the corner of Bull Royd Street and Allerton Road, Bradford.

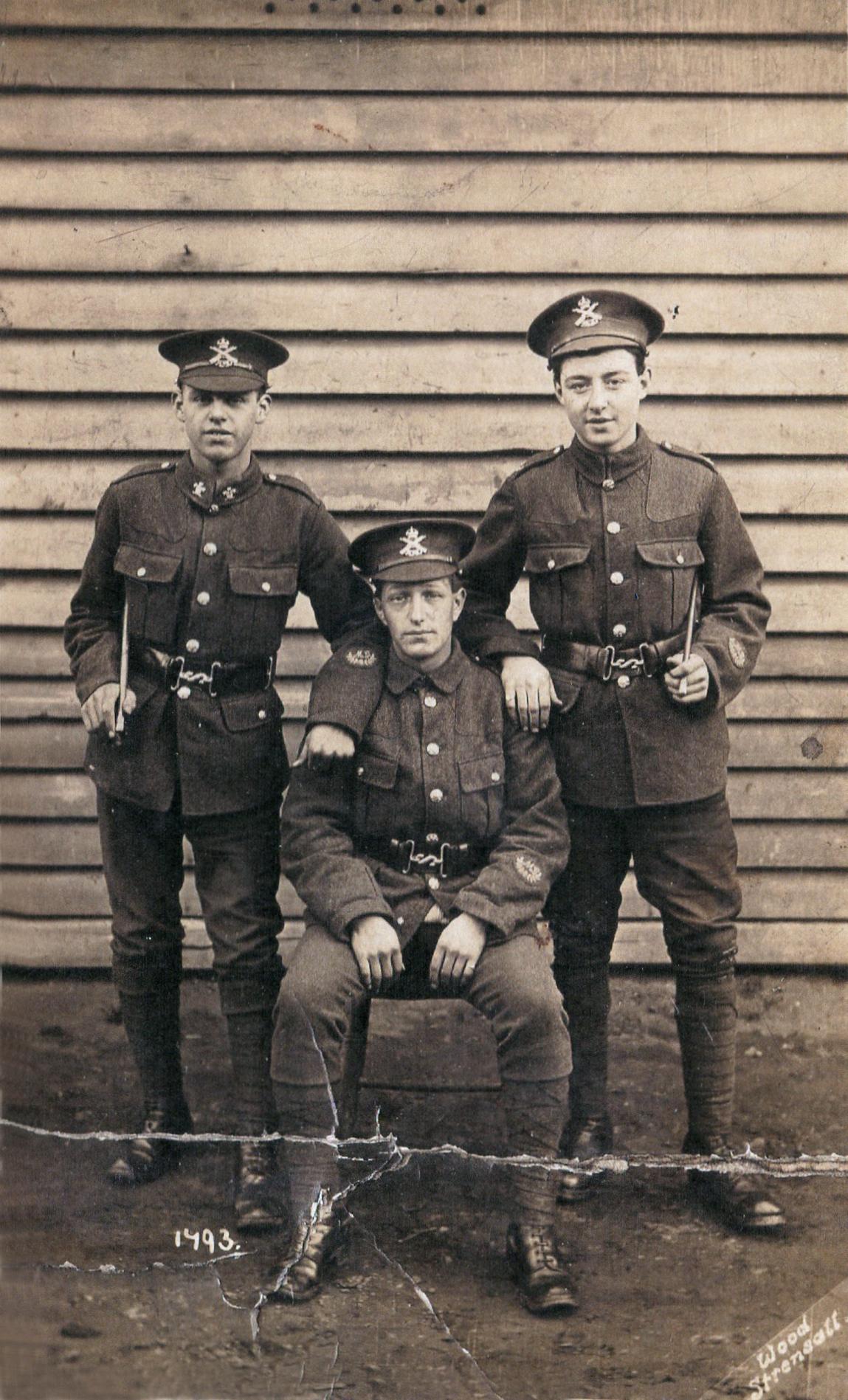

He lived in Girlington with his wife Emily and their two young sons, Jack and Percy. Shortly after the birth of Percy, in May 1915, Razzy enlisted with the West Yorkshire Regiment. Once his basic training had been completed it was off to the trenches. In the photograph, Razzy displays three brass stripes on the left sleeve which shows that he was wounded in action not once, but three times.

Up to late 1915 each infantry battalion had a Machine Gun Section consisting of a lieutenant, a sergeant, a corporal, two drivers, a batman and 12 privates trained in the maintenance, transport, loading and firing of the Vickers heavy machine gun.

These men made up two six-man gun teams. As the photograph shows, Razzy was a member of such a team within the West Yorkshire Regiment.

By February 1915 the allocation of machine-guns to each battalion had been doubled to four. This, plus other minor adjustments, changed the full establishment of the battalion to 1,021 men of all ranks.

Pioneer battalions, which were introduced in 1915, had 1,034. In action, battalion machine gun sections were increasingly collected into a brigade group of 16 guns, under a Brigade Machine Gun Officer. This arrangement was made permanent in January 1916: a month later, the gunners were formally transferred from their regiments into the newly-formed Machine Gun Corps.

When they lost control of the Vickers guns in this move, the infantry battalions received four Lewis light machine guns. By the opening of the 1916 Somme offensive this had been increased to 16 guns per battalion, and early in 1918 this was increased again to 36 guns. The firepower of the battalion was thus considerably increased throughout the war.

As a member of the 79th Machine Gun Company Razzy was sent to Salonika in 1916 as part of 79th Brigade, 26th Division. In August, 1916, the Division was in action at the Battle of Horseshoe Hill but the winter of 1916-17 saw both sides locked into the same situation as troops on the Western Front.

After completing their conquest of Serbia, the Bulgarian forces had entrenched themselves strongly among the mountainous ridges of the former Serbo-Greek frontier. In front of these entrenchments the advance of the Allied forces had been brought to a standstill, and both sides had settled down into what were virtually winter quarters.

The severity of the Balkan winter kept both sides firmly in their trenches during January and February of 1917. Shell fire was only spasmodic, and patrolling brought little loss. The only active operation during this period was a raid carried out on February 11, 1917, by the 10th Devonshire Regiment (also of 26th Division), against positions on a hill called the Petit Couronne.

There was also a enemy air raid on the evening of February 27 when a Zeppelin dropped three bombs killing several men and numerous horses and mules of the 11th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment’s transport column. However, we know from a letter sent to Emily Orwin by Edward Richie, an officer in Erasmus’s company, that during their sections time in the trenches in an area around Lake Doiran known as La Tortue, they were under considerable Bulgarian shell-fire.

A heavy shell exploded near Razzy’s machine gun team and five of the six man team, including Razzy, were killed. The Bradford Daily Telegraph of Friday, March 16, 1917 announced that Private E. Orwin, of the Machine Gun Corps, Salonika had been killed in action, at the age of 26, on February 28, 1917.

Like many women his wife Emily was now a widow and left to bring two young sons up on her own, and Razzy’s family, the Orwins were left devastated by their loss of a much loved son and brother.

For Emily and her family there was a second tragedy to deal with when Emily’s brother, Percy Winder, was reported to have been wounded and missing in action on September 21, 1917.

It wasn't until Thursday, November 22, 1917 (two months later) that the Bradford Daily Telegraph carried the announcement that he had been killed in action. Percy's body was never recovered. Emily’s dad (Joseph Winder) never got over losing Percy and died about a year after, leaving his wife Miranda to deal with the paperwork from the War Office.

Only my great aunt Lydia thought of her brother has she turned the pages of her family album."

MORE NOSTALGIA STORIES

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here