NEVER have so many fought for so long, and been recognised by so few, as the Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus who fought with the British from 1914 to 1918. They came from the villages of British India, in total 1.5 million of the Indian Army – a surprisingly significant number equivalent to around a quarter of the British Army, and more than all the Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, South African and Caribbean troops combined. Yet in the hundred years since the Armistice with Germany to end the First World War, the Indians have been largely neglected.

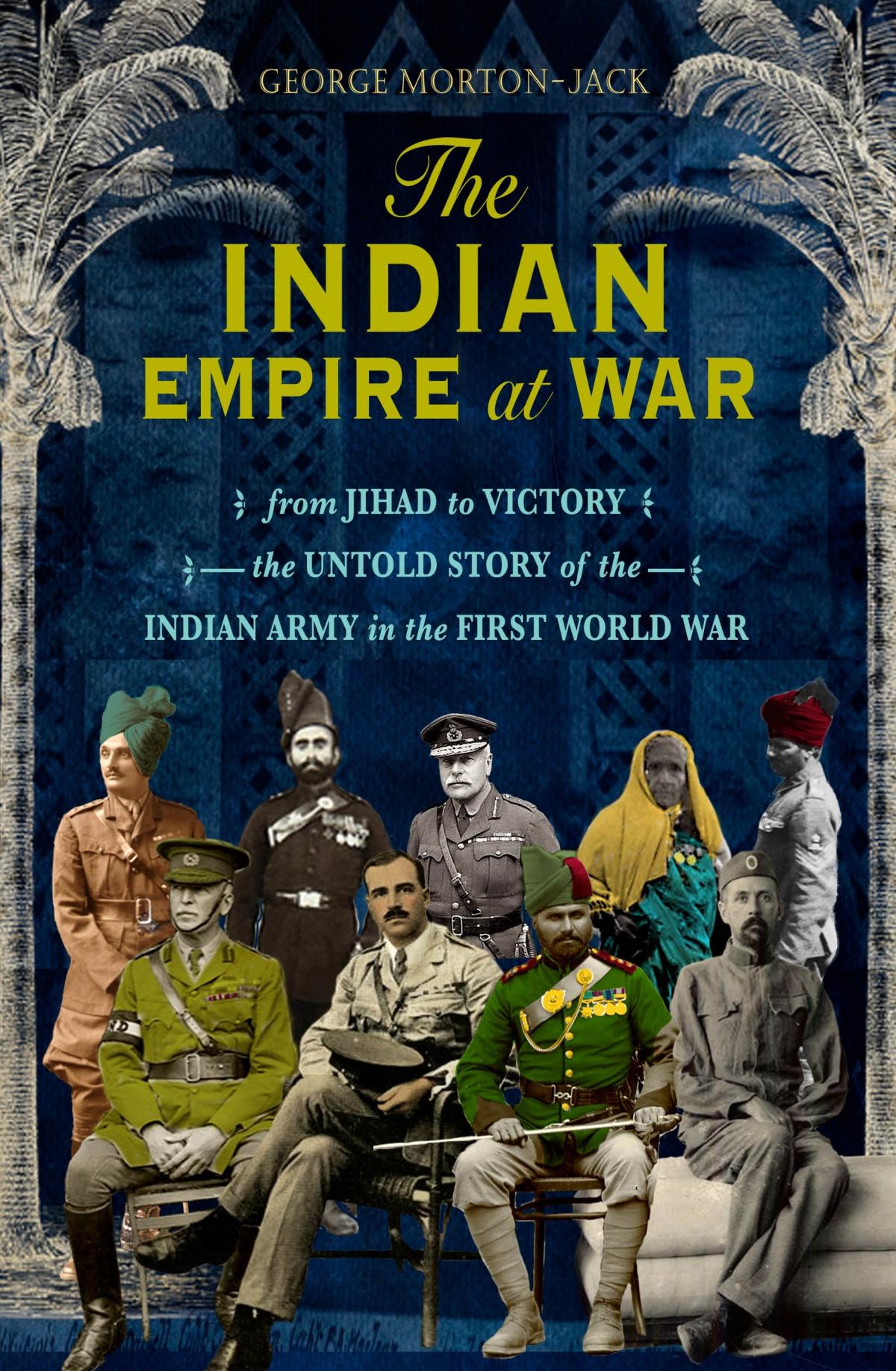

Historian George Morton-Jack’s new book, The Indian Empire at War: From Jihad to Victory, the Untold Story of the Indian Army in the First World War, is the first global narrative history of the Indian Army’s part in Allied victory. It tells the personal stories of the brothers Mir Mast and Mir Dast alongside those of Sikh and Hindu soldiers.

The war evoked by the familiar poems, plays, comedies, novels, films or history books – from Wilfred Owen, Journey’s End and Blackadder to Birdsong, War Horse and Niall Ferguson’s The Pity of War – is a white man’s war, characterized by the mud and madness of the western front.

However, the Indians were there too. And they served much more widely – in what are now some fifty countries, fighting a war that was truly global like the Second World War.

In autumn 1914, as the Germans invaded France and Belgium, the Indians under their British officers made up one third of the British Expeditionary Force on the Franco-Belgian border. At Ypres they saved the Allies from a disastrous defeat, crucially filling gaps in the thin trench line against the year’s last German offensive bidding for a decisive victory in the west.

“Each man was worth his weight in gold,” the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, said of the Indians at Ypres – he knew they had arrived in the nick of time, on British Cabinet orders, by ship and rail via Bombay, Karachi, Cairo and Marseille. Indeed, at Ypres on 31 October 1914 the Indian Army won the first of its eighteen Victoria Crosses of the war, awarded to the 20-year-old Muslim machine gunner Khudadad Khan, from the village of Dub in what is now Pakistan.

From the winter of 1914 to 1917, the Indians continued to fight the German Army on the western front to help liberate occupied France and Belgium.

They also fought the Germans in China and tropical Africa, from what are now Cameroon to Tanzania, in Allied offensives to capture German colonial possessions.

Meanwhile the Indians served across the Middle East against Germany’s Islamic ally, the Ottoman Empire with its Turkish Army. After initial battles on the Ottoman fringes of Egypt’s Western Desert, the Suez Canal, Gallipoli, Yemen and Iraq’s Basra province, the Indians attacked time and again in Allied advances to capture Baghdad, Fallujah, Ramadi, Gaza and Jerusalem. “I cannot tell you how magnificent has been the work of the whole force,” Sir Stanley Maude, the commander of the Indian expeditionary force in Iraq, wrote home from Baghdad in April 1917, “the troops have fought like tigers.”

From the Indians’ viewpoint, British service certainly had its rewards. The primary attraction of military service for them as volunteers was dependable wages and pensions – which otherwise they would not have had to help their families survive in the villages of India’s poverty-stricken rural economy.

Yet serving the British also had painful disadvantages. While the ultimate sacrifice was demanded of the Indian troops on the battlefields – approximately 34,000 Indian soldiers were killed – they were colonial subjects and daily humiliated as racial inferiors, sometimes brutally so, denied the rights of the white soldier.

“We were slaves,” as one Sikh veteran, Sujan Singh, put it in old age in his Punjabi village. The Indian recruits were racially segregated in their camps, ships and railway carriages on the way to the fronts; they had lower pay; they could suffer physical punishments illegal for white troops as inhumane; they could only hold regimental commands permanently inferior to their British officers; they had less home leave; and they had no vote in domestic elections.

Very few of the Indian troops deserted – it was risky with the punishments of lost pay and pension, or even execution by firing squad. Of those who did desert, the bulk were Muslims for whom the war against the Turks as their Islamic brothers was a source of serious moral anguish. One of them was named Mir Mast, from what is now the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, whose story was quite remarkable.

Mir Mast showed outstanding courage with his regiment on the western front in winter 1914, winning a distinguished service medal for tenacious trench fighting, throwing grenades at German infantry at close quarters. But in early 1915 he unexpectedly deserted his regiment, going over to the Germans across no man’s land. “When the war broke out with Turkey, I could not bear the news,” he later explained of his decision.

Mir Mast became a prisoner of war in Germany. He was held at a special camp for the Indians south of Berlin, where he promptly changed sides by volunteering to become a secret agent. Under German officers he embarked on a covert mission to Afghanistan in order to bring the Emir at Kabul into the war against the British. So useful was Mir Mast as a spy in German service that his officer, a Berliner, awarded him a medal for devotion to duty. This made Mir Mast probably the sole soldier of the First World War to be awarded both a British and a German medal. Mir Mast was in fact not the only prodigy in his family: his older brother Mir Dast was the second Muslim to win the Victoria Cross, at Ypres in April 1915.

By 1918, the Indian Army was a cornerstone of Allied grand strategy for victory over the Germans and Turks, with its men using their bayonets, grenades and machine guns mostly on the killing fields of Palestine and Syria.

As the Armistice of 11 November was signed in France, the Indians became occupiers of conquered enemy lands from the Rhine, Gallipoli and Istanbul to Damascus, Mosul and the Caucasus. Many of them continued to serve overseas with forces of occupation into the 1920s, until the peace treaties with Turkey were finalized.

The importance of remembering the Indians’ part in the war goes beyond the sheer size of the Indian Army’s contribution. British history should be fully inclusive of its Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus of 1914-18, recognizing their sacrifices as much as anyone else’s.

l The Indian Empire at War: From Jihad to Victory, the Untold Story of the Indian Army in the First World War (Little,Brown, £25, ebook 12.99), is available at Waterstones, Bradford, or at amazon.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel