"From October 1642 to March 1644, Bradford – which was little more than a large village – saw several bloody encounters between the Royalist forces of King Charles I and those on the side of Parliament and Oliver Cromwell.

Hundreds were killed and wounded in what Malcolm Hanson describes as “the most dangerous period of the town’s history”.

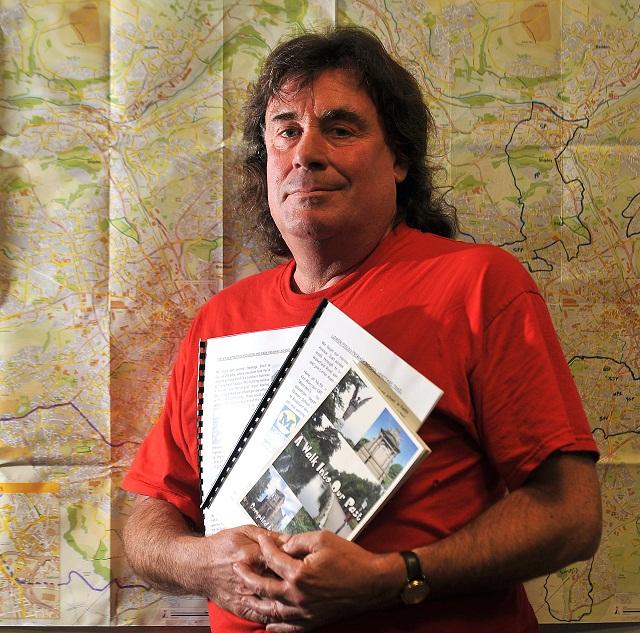

Here, he takes us on a walk across nearly four centuries, to the places where men tried hard to batter or butcher one another for the good of the cause.

“Three times our ancestors stared death in the face, yet through a ‘miracle’, coupled with the bravery of a rabble army, and finally – as tradition has it – an unknown girl frightening the Royalist Earl of Newcastle, Bradford’s brave citizens lived on to fight another day.

“We start at City Hall and the statues of all the kings and queens of England adorning the exterior walls. Here you will find the two main Civil War protagonists, King Charles I and Oliver Cromwell. Bradford was mostly for the Parliamentarian cause, since the King had dealt roughly with its people in the past. They hated him – and the feeling was mutual.

“At the bottom of Ivegate a plaque reveals the site of Parliamentarian leader Lord Fairfax’s headquarters. In 1642/3 when the siege took place, Bradford was made up of just three thoroughfares – Ivegate, Westgate and Kirkgate. Kirkgate would be pounded regularly, with many civilian lives lost.

“Three key areas were Cheapside, Forster Square and the gates to the parish church – where Bradford Cathedral is today. “Kirkgate stretched to the gates of Bradford church, and it was here, on October 23, 1642, that the town’s untrained and unarmed ‘Rabble’ army of 300 citizens readied themselves to take on a Royalist army of 800 fully-trained soldiers bent on destroying the town.

“If the Royalists could take the fortified church, Bradford would fall – yet the town would be saved (the so-called ‘miracle’) when, with a heavy snow storm developing and a cannon suddenly exploding, the Royalists were driven back to Barkerend.

“They returned to Leeds. A few days later Fairfax entered, and after fortifying the town’s defences left, taking many able-bodied men with him, leaving the depleted irregulars to await the Royalists’ return, and on December 18, back they came.

At what is now Bradford Cathedral and Vicar Lane, what would be known as the Battle of the Steeple took place. Some estimates numbered the Royalist force as 1,200 men made up of horse troops, dragoons, foot soldiers, infantry and artillery.

“The 300 Bradford irregulars defending had approximately 30 muskets with a few fowling guns – the rest were farmyard implements. Yet this gallant band of men, at the shout of ‘conquer or die!’ ran to meet the enemy full on.

“They tore up Church Bank and into the front line, cutting and slashing as they went. The Vicar Lane area became the killing fields, where the “rabble” slew so many that the track was afterwards named Dead Lane.

“One eyewitness wrote: ‘Thus with us falling on them away the enemy went, with about 50 of our own clubs and musketeers after them. The courage of our men greatly astonished the enemy, who believed that no 50 men in the world would dare take on 1,000 unless they were either drunk or mad.’ “The irregulars were neither drunk nor were they mad, they were fighting for their lives and those of their families, and perhaps something the Royalists had not understood – they were also fighting for their freedom.

“The enemy’s dead were said to be in the hundreds, including many captains. The injured numbered much the same. Captured were soldiers, horses, guns and ammunition.

“The irregulars suffered only two deaths – no man was captured, nor was it reported a single bullet lost to the enemy. It had been Bradford’s finest hour. A plaque commemorates this on the Cathedral inner wall.

“Paper Hall and the Cock and Bottle are important locations for what happened next. In 1643, Fairfax returned to defend the town with an army of 2,000 – in Leeds his father gathered a further 2,000.

“His opponent, the Earl of Newcastle, was marching to Bradford with an army of 12,000 – and the fall of Bradford was once again imminent.

“On June 30, the Bradford and Leeds army together marched off to Aldwalton, where Newcastle waited. The Battle of Adwalton Moor took place, and much of it saw the Parliamentarians besting the superior Royalists.

“But once a Parliamentarian flank was broken through, the battle was over and Fairfax and his men fled, leaving Newcastle to advance on Bradford.

“On arrival, Newcastle ordered the town to be surrounded, then to be bombarded, and finally to be destroyed: ‘Kill every man, woman and child, nothing must be left...’ “This was in response to the killing of a young Royalist officer, thought to be the Earl of Newport’s son, who had begged for quarter (mercy) from one Ralph Atkinson. “I’ll give you quarter alright, this is Bradford quarter!” Atkinson reputedly replied and killed the officer in cold blood.

“Meanwhile, Fairfax and his stragglers had re-entered in the hope of defending, but realising this was impossible, broke out early on the morning of July 2. A skirmish took place at where now stands Paper Hall (then yet to be built) and only Fairfax and a handful of men made it to safety.

“Yards away, near today’s Cock and Bottle public house, Lady Fairfax was captured. Newcastle, in a moment of gallantry, allowed the lady to live – even supplying his coach to take her safely to her husband at Leeds.

“The scene shifts to Bolling Hall. All through the night cannon rained destruction on Bradford – reports of people being blown up as they cowered on benches were numerous, and the citizens could no more than wait for the coming of dawn, when the holocaust would begin.

“Yet – according to tradition – at Bolling Hall the Earl of Newcastle was awoken by the spectre of a woman in white, who wrung her hands and pleaded with him to “pity poor Bradford”. He was so shocked that at dawn he withdrew his orders and the townsfolk were to be spared.

“When the story of the ‘Bolling Hall ghost’ emerged, writers of the day thought it to be a plucky young Bradford lass who, as a servant and having overheard the Earl issue his deadly orders, dressed up as a wraith and gave the finest performance of her life.

“Whoever she was, if the story is true, 1,000 defenceless people owed their lives to her ingenuity.”

“On March 3, 1644, Parliamentary forces drove the Royalists out of Bradford for good. In 1649, King Charles I was executed in London on a charge of high treason.

“Monarchy was abolished and England became a republic ruled by a Lord Protector – Oliver Cromwell.”

l Any school, club, society or private party wishing to go on the Siege of Bradford guided walk can contact Malcolm Hanson on 01756-798730 or e-mail malcolm.b.hanson@gmail.com.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article