“ICY shoulder for town’s defector MP”, said a headline in The Northern Echo in May 1983 as the Thornaby MP who had split from Labour to form the new Social Democratic Party struggled to get information from Stockton council.

It gives an indication of the future for the rebel MPs who have quit their parties this week to form the Independence Group.

Indeed, this week’s events are very reminiscent of the last great break in Labour in the early 1980s, a split that was fashioned in Stockton and which was given life-sustaining optimism by a fluke in Stockton. Perhaps we can predict the future by looking back on those events.

In January 1981, “the gang of four” – Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Shirley Williams and, err, the only everyone struggles to remember, Bill Rodgers, the Stockton-on-Tees MP – broke away from the increasingly left-wing Labour Party led by Michael Foot. Europe was one of their biggest concerns, as Mr Foot wanted Britain to withdraw from the European Economic Community whereas they were pro-European, but they also worried about the party’s stance on unilateral nuclear disarmament and its dependence upon the trades union movement.

Very much like today, they wanted to provide an alternative between the extremes of the Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on the right hand, and Mr Foot’s Militant Tendency-dominated Labour on the left hand.

Mr Rodgers, a Liverpudlian who’d been Stockton’s MP since 1962, was one of the architects of the split. He was famed even then for his anonymity, although there are many reasons to remember him: as a Treasury minister in 1970, he announced the abolition of the sixpence coin, and as Transport Secretary in 1976, gave the go-ahead for the Tyne and Wear Metro.

Right from his earliest days, he was regarded as a thoughtful, pro-European Labour moderate – in 1972, Harold Wilson sacked him from the shadow cabinet for leading a pro-EEC revolt, and an interview with him in the Echo in 1977 was headlined “the minister for moderation”.

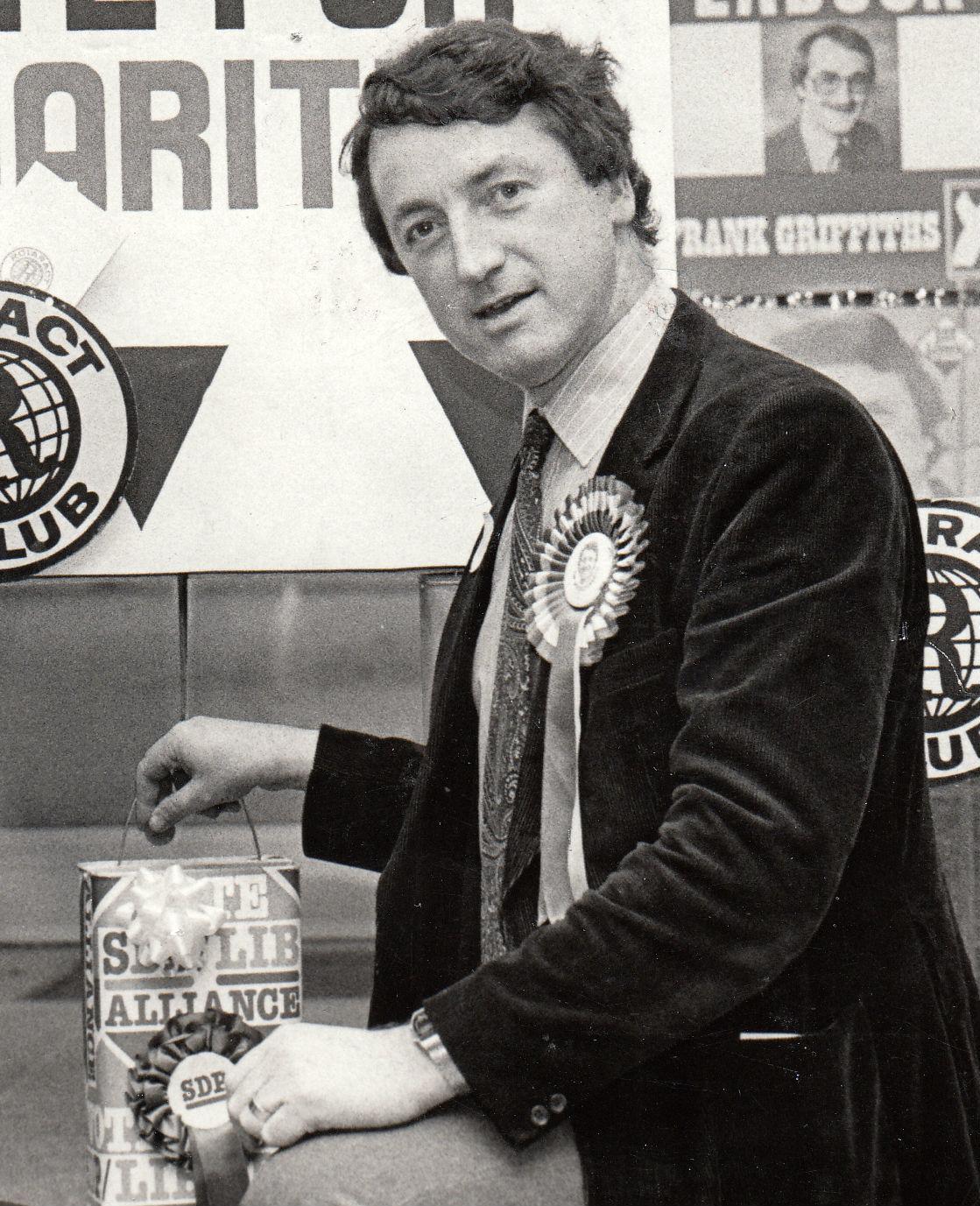

In 1981, two months after the gang of four’s initial split, another 28 Labour MPs and one Conservative joined the breakaway. The Echo said that “leading the stampede of Labour rebels” was the Thornaby MP, Ian Wrigglesworth.

From Norton-on-Tees, Mr Wrigglesworth had been Thornaby’s MP since 1974, and was also a noted moderate. In December 1980, he had resigned from Mr Foot’s shadow team because of its leftwards lurch so he could devote time to fighting the “reds under his Thornaby constituency bed” – Militant Tendency, the Echo said, had a full-time Trotskyite organiser in the town, continually agitating to deselect Mr Wrigglesworth.

Jeremy Corbyn has called for today’s splitters to resign and fight by-elections, and back in 1981, only one of the defectors sought a mandate for his change of allegiance. He was a south London MP, and despite winning 30 per cent of the vote, he lost the by-election to a Conservative.

Despite this, the SDP was initially popular. Its poll ratings touched 50 per cent, and its by-election victories in Crosby and Glasgow Hillhead, for Mrs Williams and Mr Jenkins, were great triumphs.

It entered the 1983 General Election in an alliance with the Liberal Party – for which it was mercilessly mocked by the satirical TV programme, Spitting Image. It won 25 per cent of the vote, which was very close to Labour’s 28 per cent, and could have been seen as a good result from such a standing start two years earlier.

However, the first-past-the-post system strangled the alliance: it won just 23 MPs (17 Liberals and six SDPs), whereas Labour won 209. Of course, Mrs Thatcher, with 42 per cent of the vote and 397 seats was the overwhelming winner, and Mr Foot blamed the SDP for siphoning off Labour votes.

In the Tees Valley, the constituency boundaries had been redrawn. In the new Stockton North seat, Mr Rodgers was a “political castaway”, according to the Echo, without union support or the help of party workers, and he was beaten into third place, 4,000 votes behind Labour’s Frank Cook.

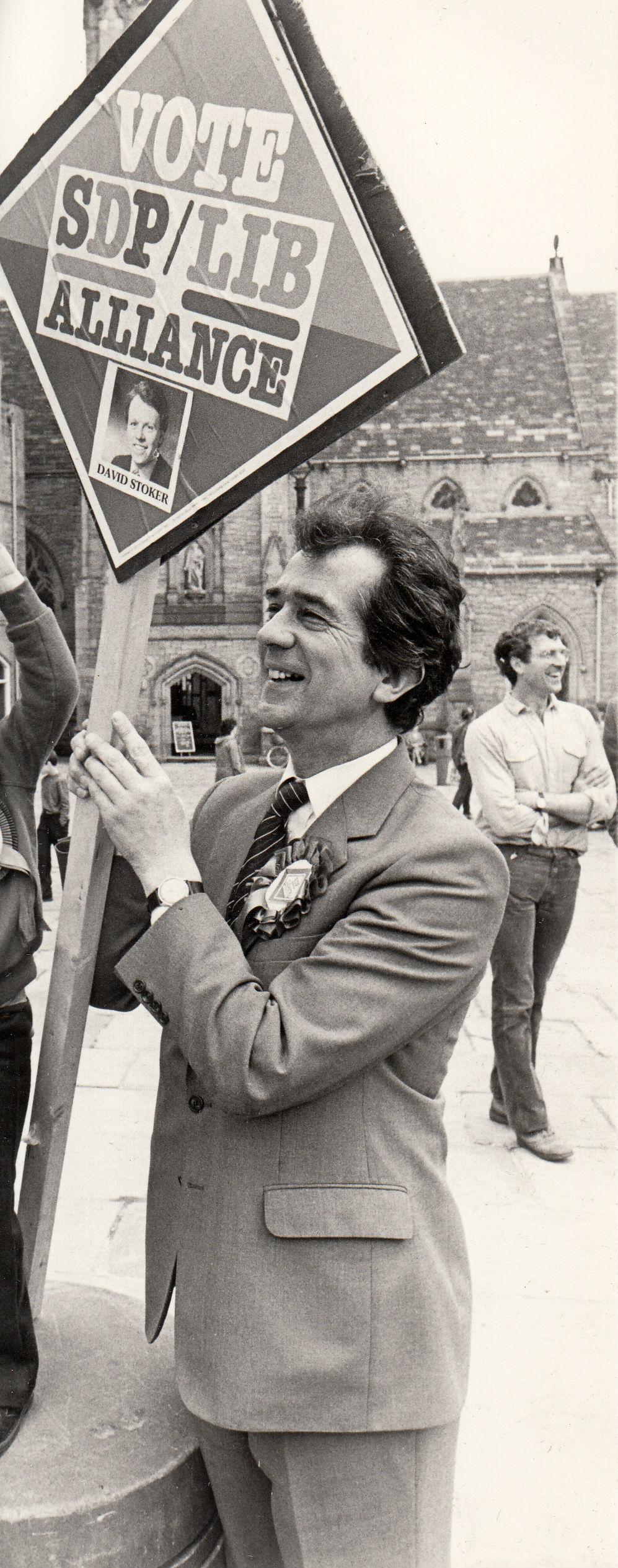

But in Stockton South, Mr Wrigglesworth triumphed. Despite the icy shoulders and despite being labelled “a traitor”, he won the seat by 102 votes – one of just six SDP victories in the country.

It was, though, a fluke. Just before polling day, it was revealed that the Conservative candidate Tom Finnegan (who, in the 1990s, came to own the Zhivagos nightclub in Darlington) had been an active member of the National Front less than a decade earlier. It was such an embarrassing revelation that Mrs Thatcher issued an apology.

Mr Wrigglesworth clung to his seat until the 1987 election when the alliance polled 23 per cent, winning 22 MPs, and immediately afterwards the two centrist parties came together to form the Liberal Democrats – both Mr Wrigglesworth and Mr Rodgers were ennobled and had senior roles in the new party.

So, on the face of it, the split succeeded only in creating rancour within party ranks. But it did lance Labour’s leftwards lean – immediately after the 1983 election, Mr Foot resigned and Neil Kinnock, urged on by the SDP’s share of the vote, began the purge of Militant Tendency.

However, it was a long process: Labour didn’t become a moderate, winning party again until 1997, by which time Mrs Thatcher and then John Major had had nearly 20 years in power.

So did the question from the 1980s is the one that’s being asked in the 21st Century: do quitters help the natural turn of politics by leaving, or would they accelerate it if they had remained?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel