There was great excitement when the first batch of German prisoners arrived in Skipton in January 1918. This was understandable. Many Skiptonians had already died in the Great War, and the townsfolk must have been desperate to see a real German in the flesh for the first time. The truth of the matter is somewhat different writes historian Alan Roberts.

SOME seventy years earlier the potato blight had been spreading across Europe en route for Ireland where the results were to be catastrophic. Mixed farming minimised the effects in south-west Germany, but the blight started a steady stream of immigrants into this country. They were able to set themselves up as pork butchers. There was a ready market in Britain for sausages as an inexpensive, nutritious and easy-to-cook food for an increasing army of industrial workers. It very soon appeared that every town had its own German pork butcher and Skipton was no exception.

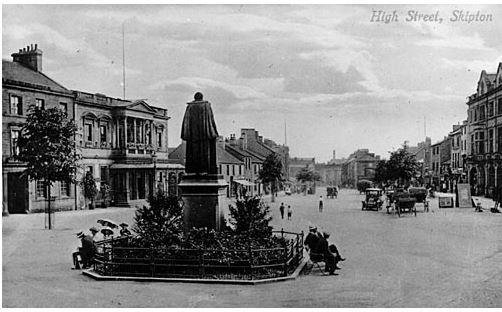

George Schulz had been born in the kingdom of Württemberg and had set up his shop at 76 High Street. In October 1911 he applied to the then Home Secretary Winston Churchill to become a naturalised British citizen. He also had a German wife Kate and an English-born daughter Ivy. Schulz would stay here throughout five years of a war in which captured German prisoners were marched in front of his shop. One of the local histories later reported the regular sight of Schulz walking through the streets with his sleeves rolled up stirring a bucket of blood to prevent it from curdling. Presumably the blood was needed for his black puddings!

Robert Bell Barrett and his family lived at the other end of the High Street behind the mighty gates of Skipton Castle where he administered both the castle and its estates for Henry James Tufton, 1st Baron Hothfield. Five resident servants catered for their needs including 40-year-old Elise Thérèse Schneider who gave her birthplace as Germany. At a time of increasing tensions between Britain and Germany she maintained that she was in fact French. The German Empire had been established shortly after German armies had forcibly seized the French territories of Alsace and Lorraine.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War an argument between Irish labourer Thomas Kelly and German pork butcher Carl Andrassy led to two nights of rioting in Keighley. On the Saturday night a mob rampaged through the centre of the town damaging several German butchers’ shops. Police reinforcements were called from neighbouring towns. The rioters finally dispersed after they were addressed by Father Joseph Russell from St Anne’s Church.

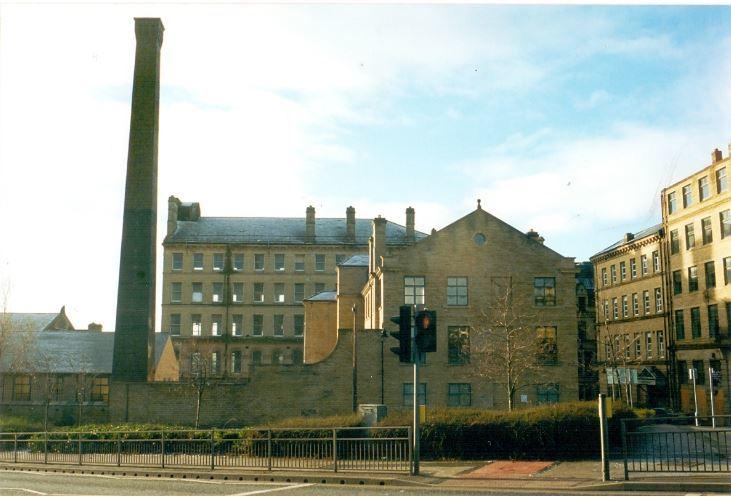

Bradford had quite a sizeable population of German textile merchants who had originally come to the city to obtain the best prices. The merchants lived in expensive villas located in Manningham and along the Aire Valley. A further group was clustered behind the Alhambra near the German church. Two mayors of Bradford, Moser and Semon, had originally been born in Germany. Bradford-born writer J.B. Priestley was proud of his city’s German population:

‘In those days a Londoner was a stranger sight than a German. There was, then, this odd mixture in pre-war Bradford. A dash of the Rhine and the Oder found its way into our grim runnel – “t’mucky beck”. Bradford was determinedly Yorkshire and provincial, yet some of its suburbs reached as far as Frankfurt and Leipzig.’

Finally Craven was to host a visit by two famous Germans. Friedrich Engels was an unlikely mix of author, revolutionary socialist and mill owner. In June 1869 he generously hosted a three-day trip from Manchester to the Yorkshire Dales for six people including fellow communist and philosopher Karl Marx and his daughter Eleanor. They stayed at the Devonshire Arms at Bolton Abbey. On the Sunday they travelled to meet geologist Dr Thomas Dakyns who was living in a farmhouse ‘in the midst of a Yorkshire wilderness’. The lower part of the farmhouse still served as a chapel and they could hear singing from a youthful choir in the room below as they tucked into a simple dinner. Dakyns had been born in the West Indies and educated at Cambridge. Writing to another daughter Jenny, Marx said that Daykins was attired like a ‘slovenly and underdressed farm servant’. Dakyns was nevertheless considered an expert in his field, and somehow rustled up the ten shillings (from his salary of just £150 a year) to be become a member of the First International (or International Workingmen’s Association).

In Manchester the group had been taken to the theatre, seen fireworks at Belle Vue and even glimpsed the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) at an agricultural show at Old Trafford. A month earlier Marx had been forced to write to his rich friend Engels asking for money. Clearly becoming a major political thinker did not always pay the bills!

And finally there were several other Germans living in Skipton in 1911. For example, there was a retired sweet seller called William Crownbeck, and a rop dresser, or gut scraper called Frederick Krauss. When the 1921 census is published next year it will become clear just how many Germans stayed in Skipton throughout the war.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel