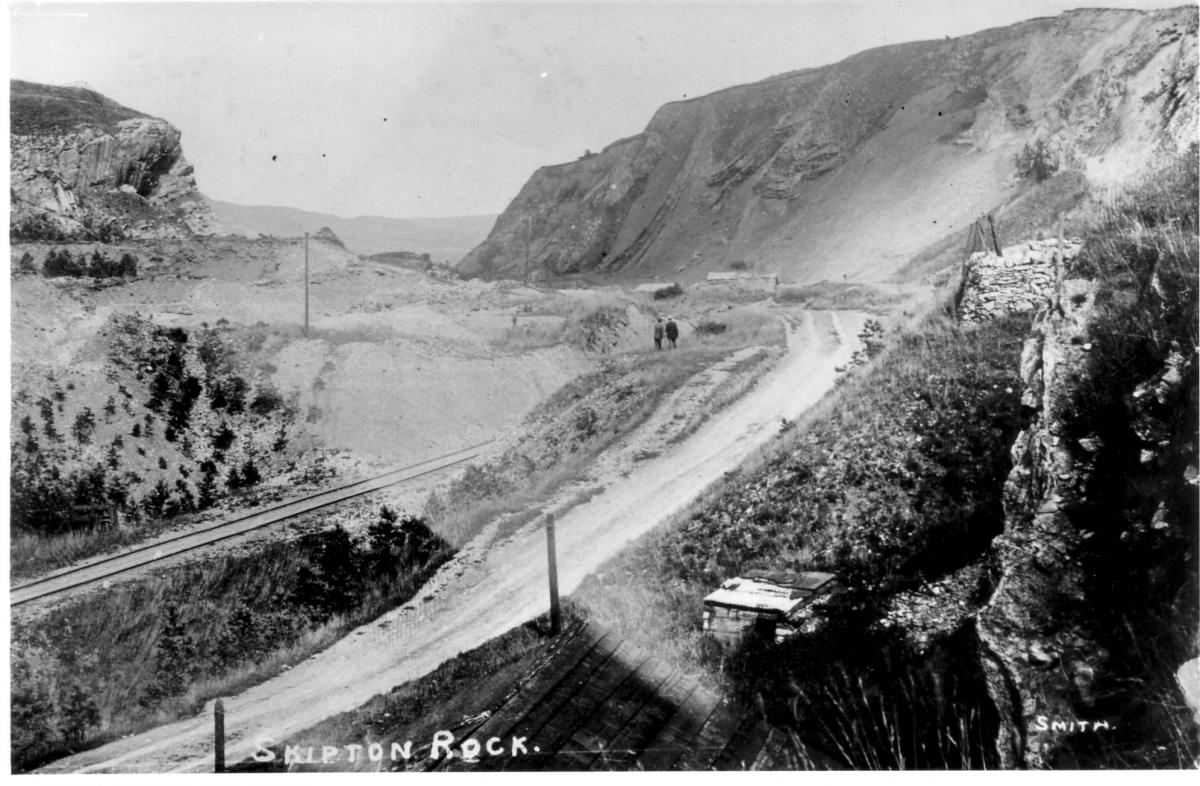

LITTLE is known of the work German WW1 prisoners in Skipton were tasked to do, once trust was secured. Here historian Alan Roberts documents some of that work taking place across Craven.

Whoever was able to work was taken by the British to work on maintaining the roads and railways, or else to work in the quarries or in agriculture. The German officers could not be forced to work; they were too busy earnestly occupying themselves behind the barbed wire at Raikeswood Camp, but the German diary records that the enlisted men could be given the chance of paid work and the prized extra rations that went with it. But where exactly were the German soldiers put to work? A Sunday newspaper, the Empire News, had sent a ‘special commissioner’ to Craven to report on what it called the German Invasion.

‘I have been spending a few days [he reported] amid the bracing moors of Yorkshire in the neighbourhood of Grassington where Germans militant [or military] and civilian are employed.’

Many Germans in Britain at the start of the war had been interned on the Isle of Man. Some were working or studying here, then there were the merchant seamen, others were on holiday or visiting relatives. The reporter was outraged: ‘You can see them with maidens and matrons flirting without hindrance’ and they were being paid up to a princely £5 a week with £1 taken off for board and lodgings.

The Craven Herald was quick to put things straight. The prisoners were simply paid the local rate for the work as agreed by the trade unions. After deductions they received around an old penny an hour for their labours. Indeed motivating the prisoners was a problem. There was little to buy with the money they did earn. The Empire News accused them of drinking to excess in the pubs when British workmen elsewhere were suffering from a shortage of beer. ‘The Quarry’, the trade magazine of the industry reported that German prisoners typically achieved around half the output of British labour, even when offered piece work rates. Civilian internees were much better workers than the military prisoners of war. Across the country thousands of German prisoners were at work in the quarries.

The late Paul Kennedy wrote a history of St Stephen’s Church in Skipton. Unfortunately the original parish documents have not survived. The book contains just a few short sentences about the Germans:

‘1919: Later they are allowed to come to St. Stephen’s. They have a fine choir. There is also a camp at Threshfield, the prisoners work at Delaney’s quarry.’

The priest from St Stephen’s used to say Mass at Raikeswood Camp, but after the Armistice the Roman Catholic officers were permitted to go to church after giving their word of honour not to escape. They were of course familiar with the Mass which was delivered in Latin, but regretted that the priest could not preach to them in their own language.

The furore surrounding events at Threshfield/Grassington led to questions being asked in the House of Commons. The Home Secretary Sir George Cave was asked for details of the camp, and the prisoners working there.

Cave replied that there was no camp, but there were twenty-one interned civilians working at Grassington: 17 of them were from Austria and the other four from Schleswig-Holstein just to the south of the Danish border. The men were supervised by civilians and housed in quarters supplied by their employer. They had to return to their quarters at nine o’clock at night.

One month later Ronald McNeill asked about aliens being seen in Grassington without any guards and frequenting public houses. The Home Secretary said that these matters had been investigated and the local Chief Constable had declared himself satisfied with the arrangements. There had recently been no further complaints.

Charley Green of Settle recalled going to Threshfield for quarry owner John Delaney who had furnished a house there so he could be near the works. There was a camp there for interned foreigners extracting dolomite from the quarry. Green was constructing a garden and one of the Austrians was providing a helping hand. ‘What a nice chap,’ he said, ‘He was not much like an enemy.’

The Austrians at work in Delaney’s quarry were interned civilians. There were no Austrian servicemen imprisoned at Skipton. It is not clear where they were housed or how strictly their movements were controlled.

German enlisted men from other camps were employed as agricultural labourers in Craven. There is no reason to doubt that some of the Skipton men were working in local quarries, but it would have made more sense for them to have worked more locally at quarries near Broughton, Thornton or Embsay.

There was a large contingent of officers from Schleswig-Holstein at Raikeswood Camp. Theirs was the unfortunate task of trying to withstand the full might of the British Army as it swept forward supported by hundreds of tanks at Cambrai. There were also a smaller number of enlisted men from the same area. It is strange that the Home Secretary specified the exact part of Germany they came from.

And John Delaney proved to be quite the entrepreneur. Not only did he own several quarries, but he also bought many tables, and wooden-framed beds at 6 shillings each when the contents of Raikeswood Camp were auctioned in June 1920.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here