It was late 1918 and Britain faced the prospect of victory on the battlefields of Europe together with a possible food shortage back home with crops left to rot in the fields due to a lack of manpower. One solution was to employ German prisoners of war to carry out agricultural work.

Historian Alan Roberts looks at when the prisoners toiled our land.

Both Britain and Germany had previously signed an international agreement about the treatment of prisoners of war and both sides were keen to abide by its terms. The result was that German officers including those at Raikeswood Camp could not be forced to work, but it was another thing for the enlisted men.

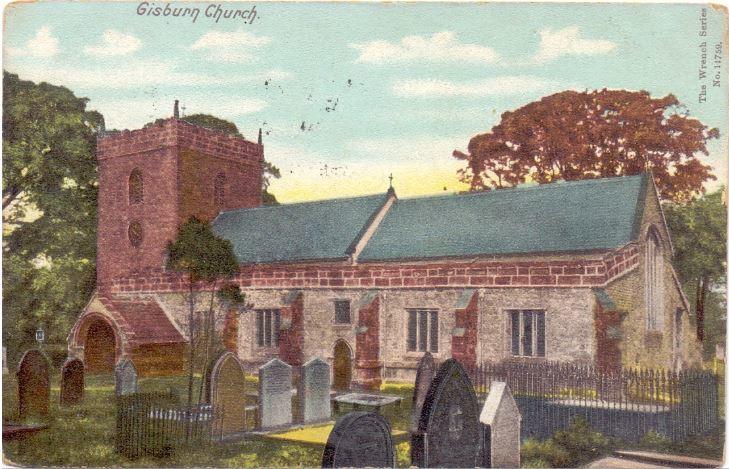

At the start of the year the Germans had been exceedingly optimistic about winning the war. A group of prisoners at Gisburn had been extremely bullish. When complimented on a fine piece of work, they had replied that they wanted everything to be in the best order for when the kaiser arrived. Fast forward to October when the much anticipated Spring Offensive had failed and the German Army was facing imminent defeat. Some refused to believe the British press saying that everything in it was ‘cooked’. Another group felt that everything was true and Germany was ‘down and done for’. Others felt that the war had been caused by German capitalists who would be richer when the war was over, while the poor would be much poorer. The first group that had once been so confident was now adopting a much more humble attitude.

In November sixteen out of thirty prisoners working at Gisburn were suffering from the flu. Most were extremely depressed by the news of the defeat. An exception said, ‘Germany no good now: me write old mother come live England.’

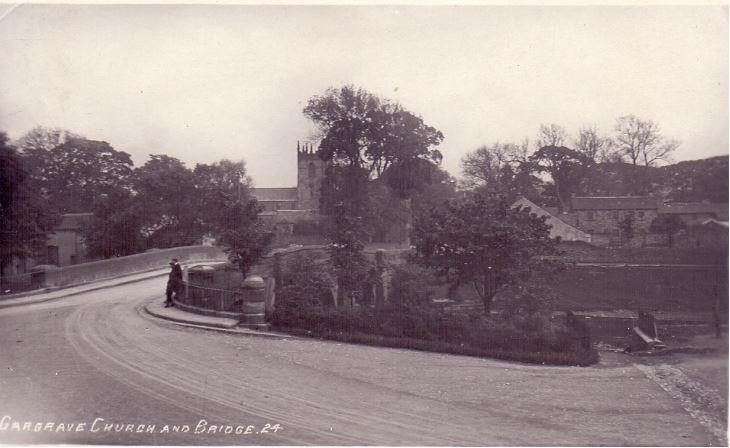

At Gargrave 20 German prisoners of war had arrived from Wetherby where they had been working gathering flax. Their arrival had created a great deal of local interest. They were accommodated in the outbuildings of the Grouse Hotel. A further twenty were located in the West Marton Institute.

When news of the end of the fighting reached Gargrave, there were celebrations in the streets with people waving flags and singing popular songs like ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’. The Craven Herald reported that German prisoners returning from their day’s work on the local farms readily saluted the British flag as they marched past.

These prisoners were paid wages at the going local rate, but were subject to deductions for their board and lodging leaving them with a net pay of between one old penny and three halfpence per hour. In truth there was little for them to buy with their money, but they did receive increased rations of food for their labours.

These prisoners had come from other prisoners-of-war camps in the north of England, but what was happening at Skipton? The German prisoners’ memoir Kriegsgefangen in Skipton was written by the officers as a record of their captivity. The enlisted men had originally been intended to act as their servants. The memoir reports that these prisoners also worked in agriculture, repairing roads and railways, and working in nearby quarries. There is some evidence that a small number of men may have been working in a quarry at Threshfield. The prospect of increased rations, being able to escape the barbed wire, and working in the open air was too enticing. Life was however far from being a bed of roses. When the British bugler blew for lights out at ten o’clock the prisoner at Skipton could breathe a sigh of relief and think, ‘Thank God, that’s another day over and done with.’

For their part the German officers were able to escape the barbed wire when they were escorted on rambles organised by the British officers and men. The officers had to sign a parole form promising not to escape. These rambles were one of the more enjoyable aspects of life at Raikeswood Camp. Extended hikes could promise temporary freedom for up to six hours and could take the officers to Bolton Abbey and beyond. On a fine day there might have been 150 participants from an officer population of around 500.

Remarkably the black-and-white postcard of Gargrave was sent in April 1918, a few months before the first German prisoners appeared. The sender Gloria has arrived there to start work, presumably in domestic service. She wrote to her friend Alice who was at Ferniehurst, a large house in Baildon. Gloria felt that Gargrave was quite a nice place and had just enjoyed a day off work. Doubtless Gloria would have learnt about the German prisoners at Gargrave if she was able to stay there long enough. Interestingly in a second postcard all the buildings on the right hand side of the street seem to have survived unaltered to this day.

Much has been written about the German officers at Raikeswood Camp during the First World War and yet there were many other prisoners working on the land in several of the surrounding communities. It is thanks to the Craven Herald and the erstwhile West Yorkshire Pioneer that this information is available to us today.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here