Skipton’s Anne Buckley, a lecturer in German and Translation Studies with the University of Leeds, provides here a detailed insight into the German prisoners held at Raikeswood Camp including the men’s occupations, home towns and injuries.

Lovers of statistics will appreciate this fascinating delve into the men who were imprisoned in Skipton in WW1.

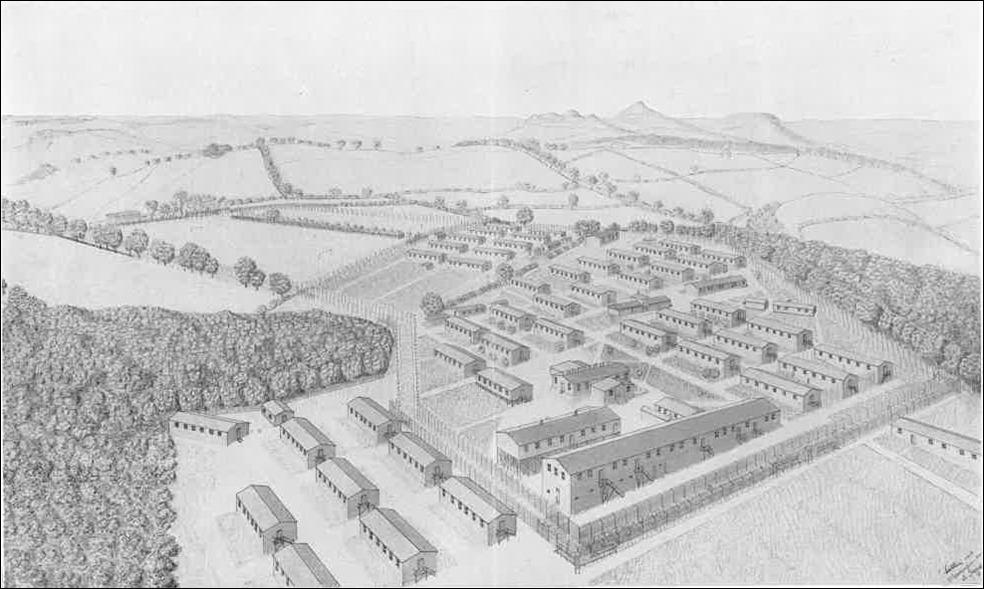

USING the records of the International Red Cross, it has been possible to identify 916 of the Germans who were incarcerated in the camp in Skipton during its existence from January 1918 until October 1919.

We believe that this represents at least 99 percent of the total number.

As Skipton was an officers’ camp the vast majority of these men were officers, but there were also enlisted men and NCOs who acted as orderlies to the officers.

The peak occupancy was approximately 550 officers and 120 men.

The men came from various different branches of the military. While the majority were from the Army there were also some naval personnel including 14 U-boat officers, of whom seven were commanders.

These included Ralph Wenninger, who was one of the most successful U-boat captains of the First World War.

There were at least 26 airmen, including flying ace Joachim von Bertrab.

Of the 916 men, 592 were reservists who had a wide range of different careers in civilian life.

The International Red Cross only started recording the men’s occupations in June 1918 so we only have this information for the final 221 men to arrive at the camp.

Of these, there were 34 teachers, 23 businessmen, 10 farmers and eight bank workers including one manager.

There were five fully-qualified doctors and four in training, three gardeners, three barbers and three engineers.

Other occupations included accountant, baker, judge, chemist, dentist, butcher, plumber, waiter, tailor, shoemaker, locksmith, wheelwright, customs official, architect and pharmacist.

There were 17 students and 14 of the men were still at school.

One of the teachers was Willy Cossmann who, along with Fritz Sachsse, compiled diary entries and accounts written by the prisoners into a book, Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, which was published in Munich in 1920.

Cossmann also set up a sixth form in the camp for the younger officers who had not been able to complete their schooling before the war.

Exams were set and taken in the camp and the students were awarded their qualifications by the Prussian Ministry of Education.

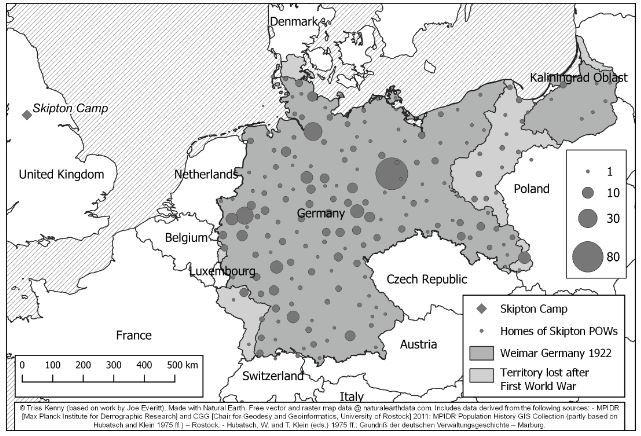

The German prisoners came from all over the German Empire.

The state of Bavaria and the Prussian provinces of Brandenburg and the Rhine were home to the greatest number of Skipton prisoners: 79, 106 and 81 respectively. Seventy of the men lived in the Berlin area, and 26 in Hamburg.

Local identity was important to the men and they formed regional societies in the camp and organised entertainment evenings with traditional music and dancing.

A further and much more serious consequence of this regional spread arose after the war, when Germany lost 13 per cent of its land and 10 per cent of its population following the Treaty of Versailles.

This meant that some of the Skipton prisoners returned home to areas that were no longer part of the German Empire or areas that were transferred to other countries shortly afterwards following plebiscites.

These areas included Alsace-Lorraine, which was returned to France, Northern Schleswig, which became Danish, Malmedy, which was given to Belgium and most of West Prussia, which went to Poland.

In the book written by the German prisoners (Kriegsgefangen in Skipton) there are only a small number of references to their battlefield injuries.

However, analysis of the International Red Cross records shows that, of the 916 Skipton prisoners identified, 322 (35 per cent) of them had injuries at the time of capture and 18 (2 per cent) of them were sick.

Of the 322 prisoners with injuries, 249 (77 per cent) had sustained gunshot wounds – this represents over a quarter (27 per cent) of the prisoners.

There were five men with amputations (a leg, an arm, a hand and two with finger loss.

Twenty men had fractures, 12 of the leg or foot, six of the arm or wrist and 2 of the jaw.

Some men had multiple injuries, one of whom had suffered a compound fracture of the skull in addition to fractures of the tibia and femur.

One of the most seriously injured men was Otto von Kühlewein.

He was captured on the Western Front on April 13, 1918 with gunshot wounds to his side, neck and left arm, which had to be amputated.

After four months in hospital in Dartford he arrived in Skipton on August 16, 1918.

He was taken to Brocton Military hospital on October 17 and repatriated six days later, but died within three weeks aged 29.

The work to obtain data from the International Red Cross records was carried out by Anne Buckley’s partner Triss Kenny and verified by University of Leeds History students Alice Craft and Joe Everitt.

Joe, of West Burton, in Bishopdale, focused on the men’s home towns and produced the map.

An English translation of the book written by the German prisoners (Kriegsgefangen in Skipton) has been painstakingly produced by staff and students from the University of Leeds and edited by Anne Buckley.

It is scheduled to be published by Pen & Sword in February 2021.

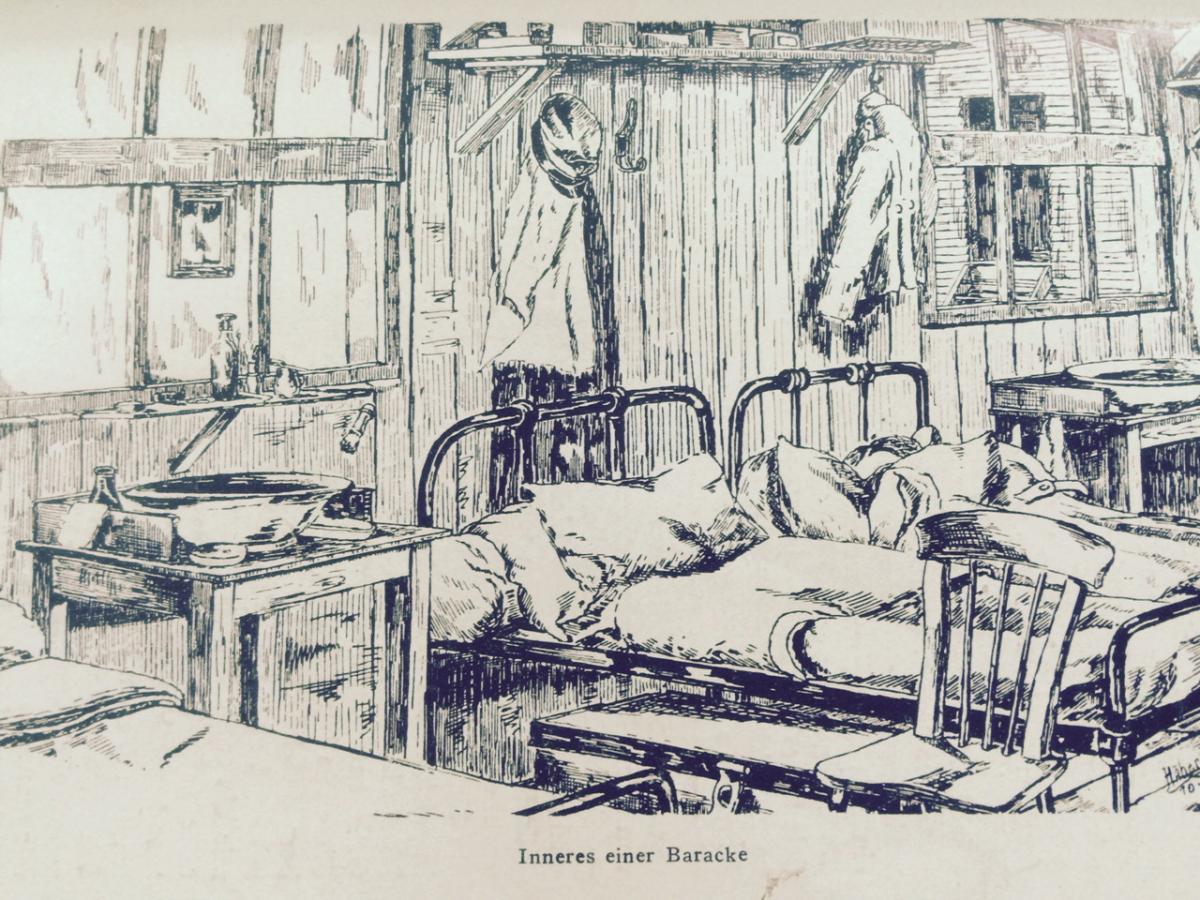

Notes and sketches for the original book were written down and smuggled out of camp when the prisoners were released and make into a fascinating diary.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here