Sport was an important part of daily life for the German officers and men imprisoned in Raikeswood camp in Skipton during the First World War.

Here, researcher and lecturer Anne Buckley who has been helping translate the diary Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, written in secret by prisoners, provides a translated extract from the book. The original piece was written by prisoner Friedrich Eppensteiner.

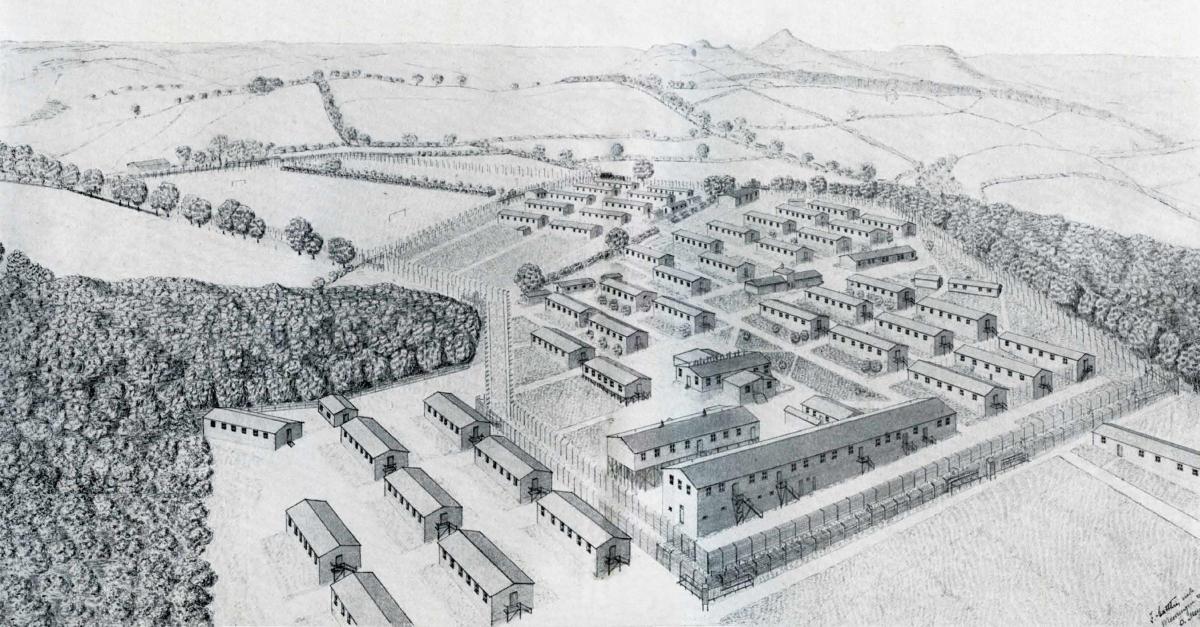

The main sports field was situated on what is now part of Rockwood Drive and Stirtonber while the adjacent smaller sports field is now grazing land.

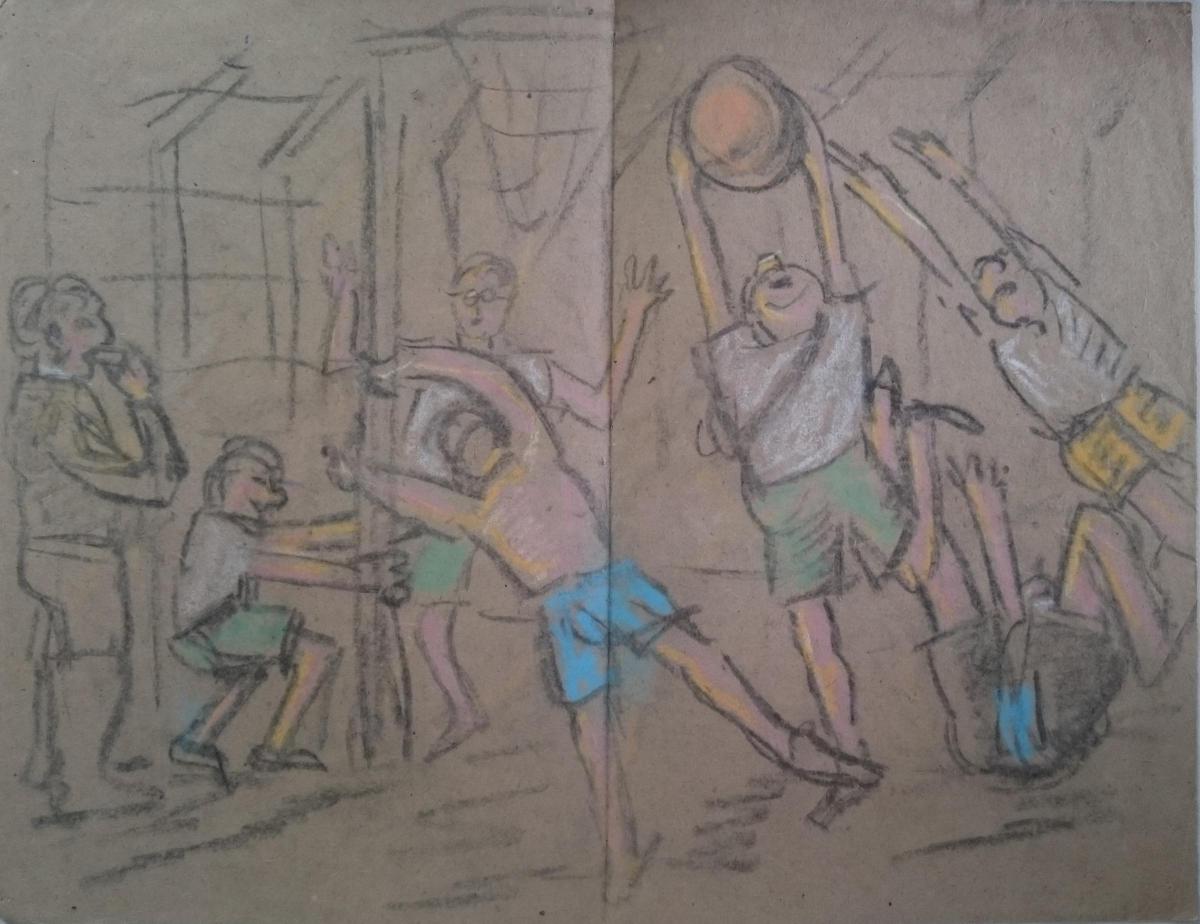

The men enjoyed football, Schlagball (similar to baseball), fistball, basketball, tennis and athletics.

One of the prisoners, Ludwig Hofmeister, had been the Bayern Munich goalkeeper before the war and even played two games for the German national team. Following repatriation he played two more seasons for Bayern Munich from 1920-1922.

In this extract from the English translation of the book written by the German prisoners, Friedrich Eppensteiner describes the sport in the camp.

The translated book is to be published by Pen & Sword in February 2021. Eppensteiner went on to become a secondary school teacher and published a book entitled ‘Der Sport’ in 1964.

Contact has recently been made with his family by University of Leeds student Harriet Purbrick, who is working with lecturer Anne Buckley on the Raikeswood Camp project.

Next week Harriet will write about Eppensteiner’s life, including a letter he sent from Skipton to his brother in America.

The sports ground: a grassy field, approximately a hectare in size, just about large enough for a football pitch.

It does, however, slope down steeply towards the southern corner. But what does that matter? A true footballer will overcome such obstacles if necessary.

So, with the goal posts erected and some balls purchased, the sports ground is ready for use!

There is the main field, which is the football pitch. And further north, separated from the football pitch by a hedge consisting of young trees and an old ash, there is a second field the same length as the main field but only half the width – but without a steep slope. Entrance to the smaller field is via a wide gap in the hedge at the lower end or a narrow gap at the upper end.

This field is very useful for games requiring a smaller pitch and for practising athletics.

Placed at the disposal of the 500 German officers and 100 men condemned by fate to be prisoners of war, how could such a sports field fail to provide them with joyful and energetic activity?

And yet, during the summer of 1918, it was not to happen due to external circumstances.

Soon after the sports ground was opened, the English reprisals came into force, which included the closure of the sports ground.

When it became accessible again in the late summer, the continually poor weather meant that very little sport could take place.

In 1919 things were entirely different.

The summer was exceptionally dry with week after week of good weather.

We were allowed increasingly longer access to the sports ground; eventually it could be used from early in the morning until late in the evening.

This was the time when our sporting activity reached its peak and when the most colourful images and the most lively activity could be seen on the sports ground.

About one in ten comrades in the camp participated in football.

The game requires skills that cannot be learnt at an advanced age or in a matter of a few weeks.

We only had three to four teams of 11 players, who all knew each other very well personally, and were part of the same community.

This number was too small to provide an incentive for real competition, and in this respect the camp football matches could be compared to those of a local football club whose spark is only fully ignited by the prospect of competition against teams from further afield.

In the games between officers and men, one could definitely detect more of a will to win, but it was enacted with an acrimony arising from the depths of the non-sporting soul.

Alongside the games in the camp, athletic exercises became increasingly popular following the formation of the athletics society in April 1918.

A sandpit was prepared for long jump and high jump, which unfortunately had to be made slightly too narrow because of the adjacent fistball pitch.

A 400m track was marked out as well as was possible given the unsuitable terrain.

We also obtained some simple equipment: a 7¼kg shot put, 2 discuses and 1 Schleuderball.

With this simple set-up, the athletes in the camp were able to do their training, which, though falling short of the full range of events in the classical Greek pentathlon, nevertheless enabled excellent physical exercise for the attainment of both strength and beauty.

The greatest non-sporting interest, where the focus was exclusively on the winners, was generated by the relay races, which were not just about camaraderie and personal relationships, but also the element of risk

The amount bet on these team races was therefore especially high and indeed the totaliser played a major role in sport because of the conditions produced by camp life.

It must, however, be said that all forms of betting must be regarded as an enemy of pure physical exercise and should be discouraged.

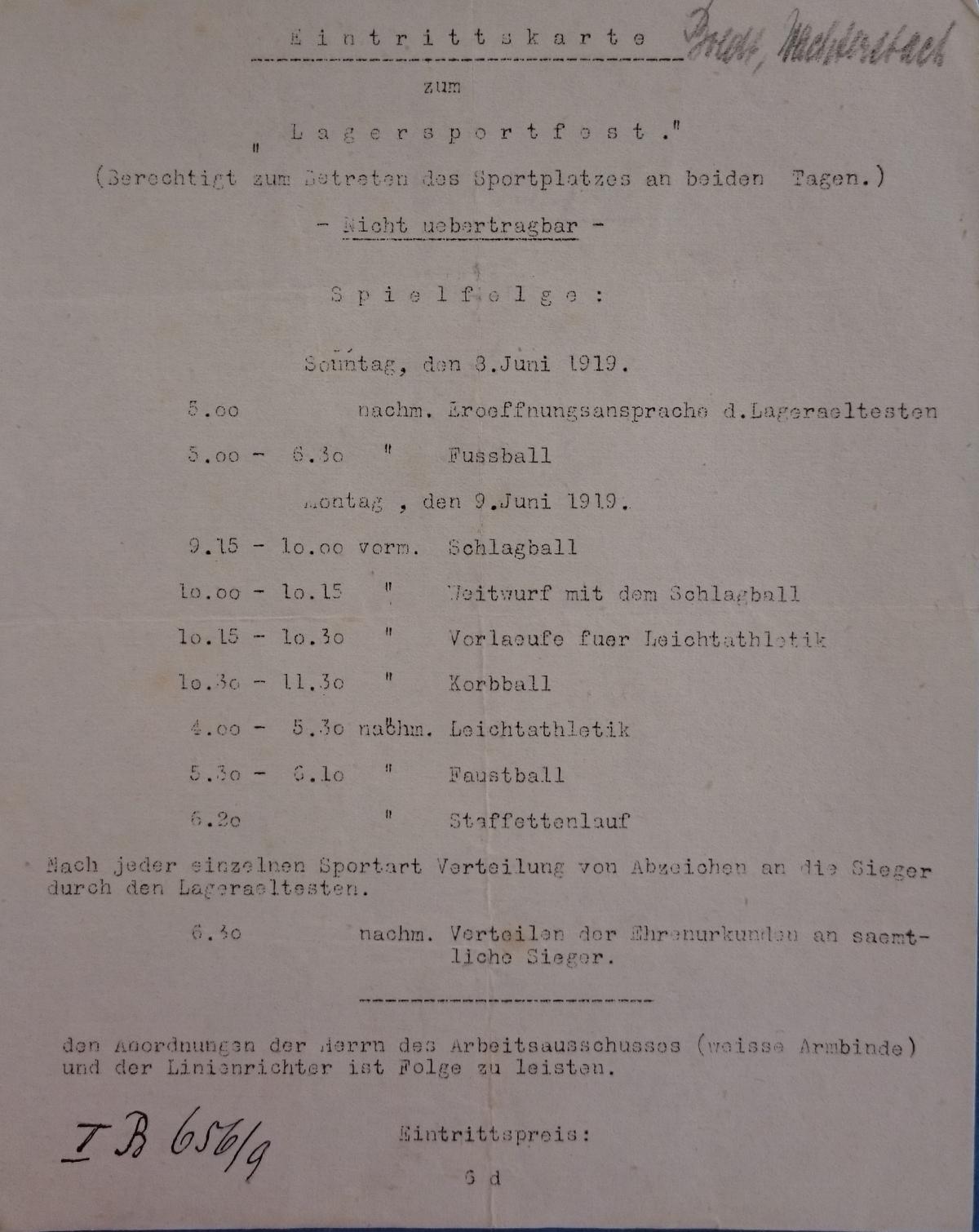

In total, three large sports festivals were held in the Skipton camp, or four if the tennis tournament is included.

All of them were blessed with superb weather. The first major sports and games festival was opened by the senior German officer with an entertaining speech on the afternoon of Whit Sunday.

The main events were on Whit Monday.

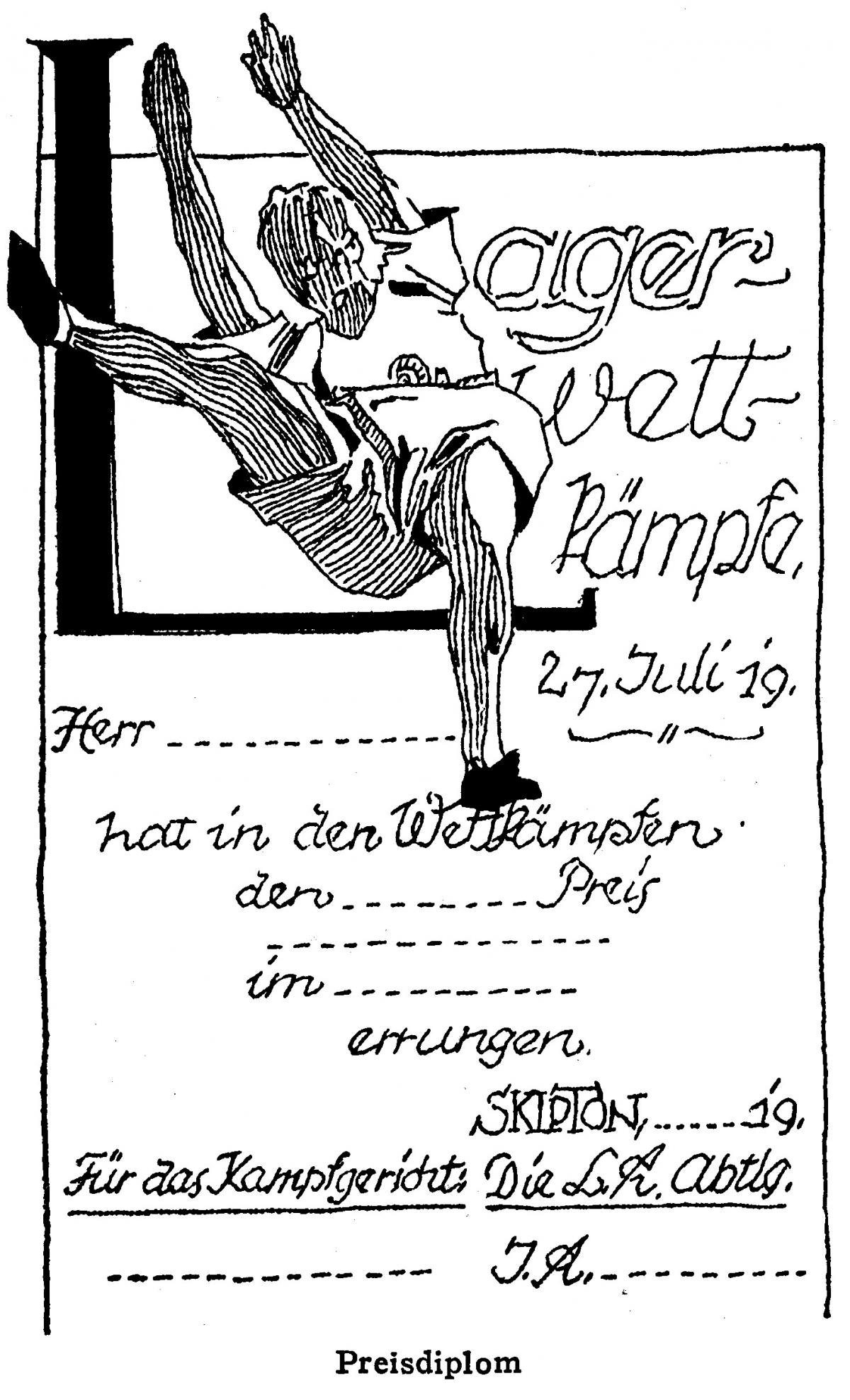

The second camp sports festival, on July 27, 1919, featured only athletics competitions but with a much wider range of events.

Contributions from comrades enabled us to provide numerous handsome prizes with a total value of around £30.

The autumn competition on September 7 was a smaller affair, involving only the members of the athletics club who had not previously won prizes.

Without doubt, sport was a ray of light in the lives of the prisoners of war, both individually and collectively.

It would not be exaggerating to say that it was only through sport in our prisoner-of-war camp that some men experienced for themselves the benefits of habitual daily activity in the fresh air, within healthy limits, for the maintenance of physical fitness as well as for intellectual capability and for refreshing the mind; and that habitual physical activity within the limits imposed by one’s work can actually be considered a moral obligation of every citizen.

More attention will have to be paid to sport and games in post-war Germany, and they will have important functions to fulfil.

What is most important, alongside the appropriate organisation of physical and patriotic development, is the German concept of sport as a schooling of the body to higher moral purposes.

May I conclude by expressing the wish that every ‘Skiptoner’ who, as a father, educator or citizen, will one day have to concern himself with the issue of physical fitness or physical education, might be inspired by his own experience in the camp to adopt a positive attitude?”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here