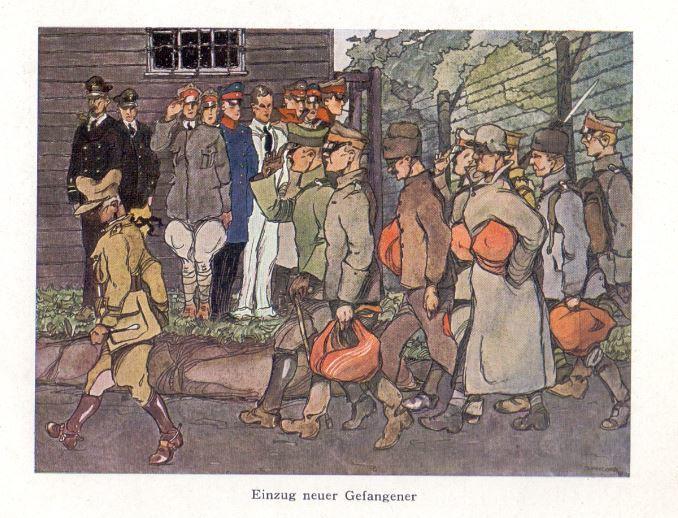

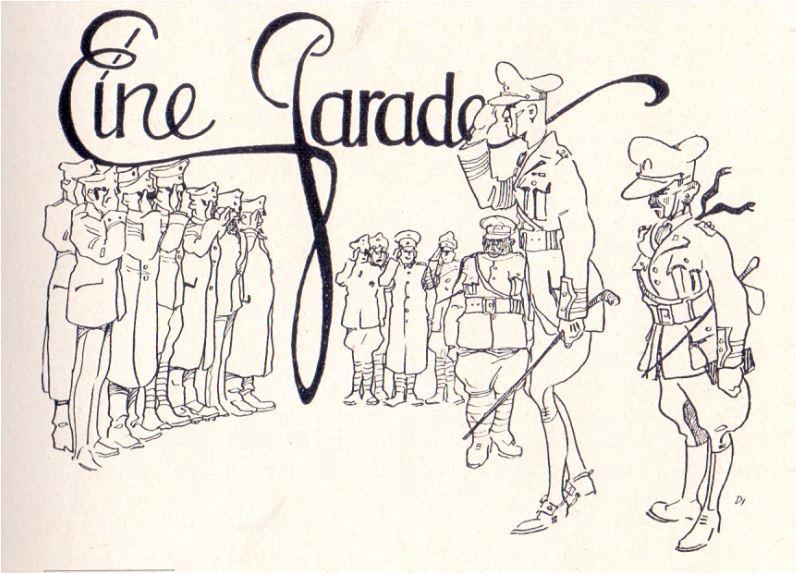

AS soon as they arrived At Skipton’s Raikeswood prisoner of war camp. the German officers realised that they would have to be extremely careful in their dealings with I-can-kill-you, although they found his exaggerated posturing a source of great amusement, writes historian Alan Roberts.

In their memoir Kriegsgefangen in Skipton the German officers proposed two alternative reasons for the nickname. In one version Parkhurst had been the British commandant of a PoW camp in France and had threatened some uncooperative German prisoners with his pistol, thundering ‘I can kill you.’ The other version allegedly took place during fierce fighting on the Western Front where Parkhurst had confronted an unarmed German officer at close quarters and had uttered those very same words ‘I can kill you’. The German officers suggested that one day the truth would emerge. The truth was in fact stranger than anyone could have imagined.

Parkhurst had been a colliery owner’s clerk in south Wales and would later be found as part of a recruiting team delivering stirring speeches to the local miners’ institutes. Offering a free trip to Berlin, he announced that he was looking for young men to fight for the honour of Wales. After all, his father had fought in the Crimea and his grandfather at Waterloo.

In early 1916 Parkhurst was receiving his final training before active service in France. Shortly afterwards he was found ‘in a highly nervous condition, heart action excited with a very rapid pulse. He states that he sleeps badly’. The condition, then known as neurasthenia, was ascribed to ‘hard work in training’ on Salisbury Plain. Today we would be more familiar with the terms shell shock or PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder).

Parkhurst would eventually see service in France. His work involved escorting German prisoners from the barbed wire enclosures immediately behind the front line to the port of Le Havre and transporting them to Britain. Even here matters did not run smoothly. After just over a year he was returned to England in a debilitated condition and immediately hospitalised. When he was sufficiently recovered he was sent to receive training in readiness for his duties as the adjutant at Skipton Officers’ Prisoner-of-War Camp.

It reads like a work of fiction: the recruiting officer who never actually made it to the front himself. Today we would recognise the symptoms of mental illness, although it is still not fully understood why some people are more predisposed to this kind of ill health than others. There is not a shred of evidence to suggest that Parkhurst was anything but an extremely conscientious officer.

The German officers understandably felt that I-can-kill-you, as they called him, was too curious for his own good. After a mass escape from a prisoner-of-war camp in the East Midlands, the Nottinghamshire Chief Constable was extremely critical of security in the camp. He said that it had become customary for the German officers to police themselves, with the British guards restricted to patrolling the outside of the camp. Five of the escapers were later transferred to Skipton. There certainly was a need for a zealous and inquisitive officer in the camp.

As the war drew to an end there was a change in the leadership at Skipton. Parkhurst was promoted to major and became the assistant commandant. The new British commandant Colonel Ronaldson was far more understanding of the Germans’ plight. This new regime and the reduced threat posed by the prisoners brought about a change in Parkhurst’s attitude. Fritz Sachsse, the German Senior Officer, reluctantly conceded that Parkhurst had done much for the camp which was above and beyond the call of duty. It was a major coup for the German officers and men to be treated at Keighley War Hospital during the flu epidemic when other options in Skipton were unavailable. Sachsse also noted that the older officers liked to drink a lot while the German memoir refers to Parkhurst’s red drinker’s nose.

After each spell in hospital Parkhurst’s fitness level was downgraded. Eventually he was only considered fit enough for duties at home and was subject to health checks every three months. There is a short note in Parkhurst’s War Office file from December 1918 which read ‘This officer cannot be spared at present’. He cannot have been doing too bad a job at Skipton!

And so it was that Horatio Parkhurst served at Skipton Camp from the day it opened until the last German prisoners departed from Hull in late 1919. His retirement to his beloved Wales would be short as his health problems would eventually catch up with him.

Self-important, driven, but undoubtedly conscientious, I-can-kill-you was not the most lovable individual. He doubtless regretted not being sent to France with the rest of his regiment. Seven out of 31 officers in his battalion would die, three of them at the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here