EACH town had its own brewery and this Mumme-Bier brewed in Braunschweig was dark, aromatic and very strong which led it to becoming an export sensation in the late Middle Ages. It did not go off on long voyages to the tropics and apparently helped ward off scurvy.

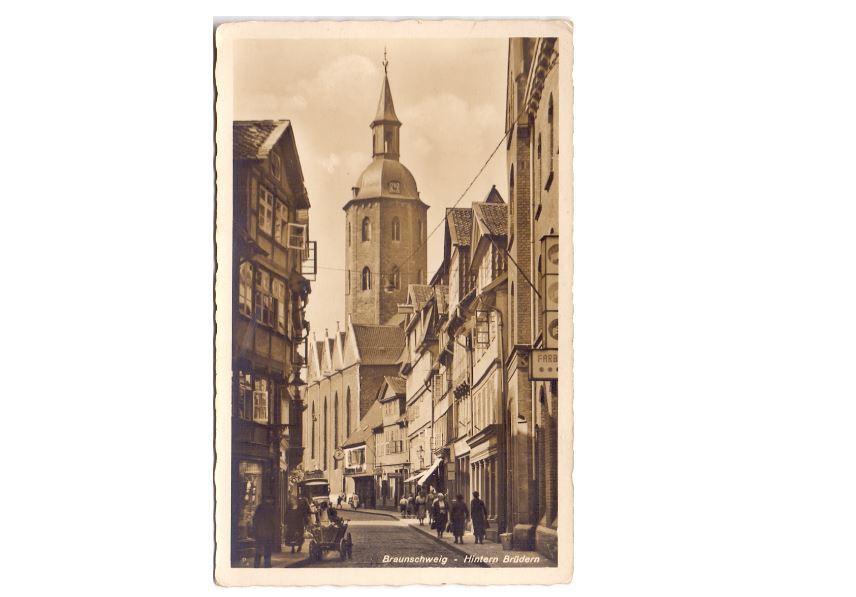

The Nettelbeck brewery’s headquarters were at 18 Hintern Brüdern. Located in a five-hundred-year-old wooden building this must have been a veritable hive of activity. There was a furniture dealer, a tailor, two decorators, a laundry and the homes of two widows. Extending to a height of seven storeys with three shop fronts at ground level and a broad gated archway providing access to a courtyard, this building was certainly impressive. This was where Skipton prisoner Musketeer Willy Koch lived along with widow Wilhelmine Blumenberg. She was listed as an official resident, but he was not. One wonders whether he was a servant, a relative or perhaps even a lover.

The postcard reproduced on this page shows the street where Koch was living. On the reverse side someone has written in German ‘a narrow street with wooden houses like in the olden days’ and dated 8 January 1944. Nine months later RAF Bomber Command demonstrated its overwhelming superiority. A combination of high-explosive and incendiary bombs destroyed the historic town centre which contained hundreds of wooden-built buildings dating from the Middle Ages.

Thanks to the British prisoner-of-war lists which survived the Blitz in 1940 in the hands of the Red Cross in Geneva, it is possible to build up a unique picture of the German prisoners at Skipton Camp including where they lived and where they were born. Two World Wars have considerably reduced the size of Germany with territory lost to several countries including France in the west, Poland and Russia in the east and Denmark in the north. Around 60% of the prisoners at Skipton gave a unique address including, for example, the street and house number. The effects of the destruction inflicted in the Second World War by the Allies and the post-war reconstruction of Germany frequently make it impossible to find these houses.

With over 900 prisoners there can hardly have been a major town in Germany which was not represented at Skipton. There were seven prisoners from the town of Krefeld including two officers from the same street. Even more unusual two prisoners from the port of Flensburg near the Danish border also shared the same house: in fact they were brothers. One of the last officers to enter Skipton Camp was Lorenz Ketelsen who arrived in May 1919. Younger brother Christian was one of the first officers to arrive in January 1918. Both officers had served with different regiments and were captured in different countries (France and Belgium) in different years (1917 and 1918).

Some Skipton prisoners lived in highly desirable residences. Second Lieutenant Fritz Brendel was born in the magnificent castle at Schloss Allstedt in central Germany while another young officer Julius Sommer lived at the imposing Old Castle in Stuttgart where his mother Adele was believed to have been a lady in waiting to the last queen of the German kingdom of Württemberg.

There is one other truly remarkable story which concerns the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. When Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812 the seriously weakened Kingdom of Prussia was an extremely unwilling partner in the venture. The Prussians did succeed in capturing around 2000 Russian soldiers, but in an unusual twist of fate the Prussian king was a huge fan of Russian music, and auditions were held to form a choir from among their ranks. Napoleon’s campaign would eventually result in failure as he and his Grand Armée ignominiously trudged back from Russia facing the perils of disease, hunger and the Russian winter. Suffice it to say that Prussia promptly swapped sides and set in motion a course of events which would lead to Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo.

Things had moved on apace in Berlin too. The Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III had by now become good friends with the Russian tsar Alexander I so that when he died, the Prussian king resolved to build a memorial in the tsar’s honour. The memorial would take the form of an idealised Russian village laid out in parkland at nearby Potsdam. The village would house the remaining twelve survivors of the Russian choir. Each of the large ornately carved one or two-storeyed houses was provided with both a large garden for growing vegetables and a cow to provide milk.

Every house was to remain in the possession of each chorister’s family in perpetuity, but this did not work out. Skipton prisoner Hans Sujata’s father had been a member of the palace guard and in 1914 was leasing a house in the village. His son an eighteen-year-old naval cadet and later a prisoner at Skipton had the misfortune to be captured by the British just hours into his very first voyage. He wrote to his mother shortly afterwards asking for tobacco, money and some underwear.

The destructive effects of war ultimately led to the construction of the Russian village in Potsdam near Berlin which is now part of a World Heritage Site. One house in the village is open to the public as a museum. The officers and men at Skipton had certainly been well treated, but for sheer good fortune as a prisoner of war the story of the twelve Russian choristers is hard to beat.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here