BOMBER commander Franz Schulte was held as a prisoner of war at Raikeswood Camp, he died in the influenza pandemic of 1919 and was buried at Morton Cemetery near Keighley.

Historian Alan Roberts looks at his brief encounter with Skipton.

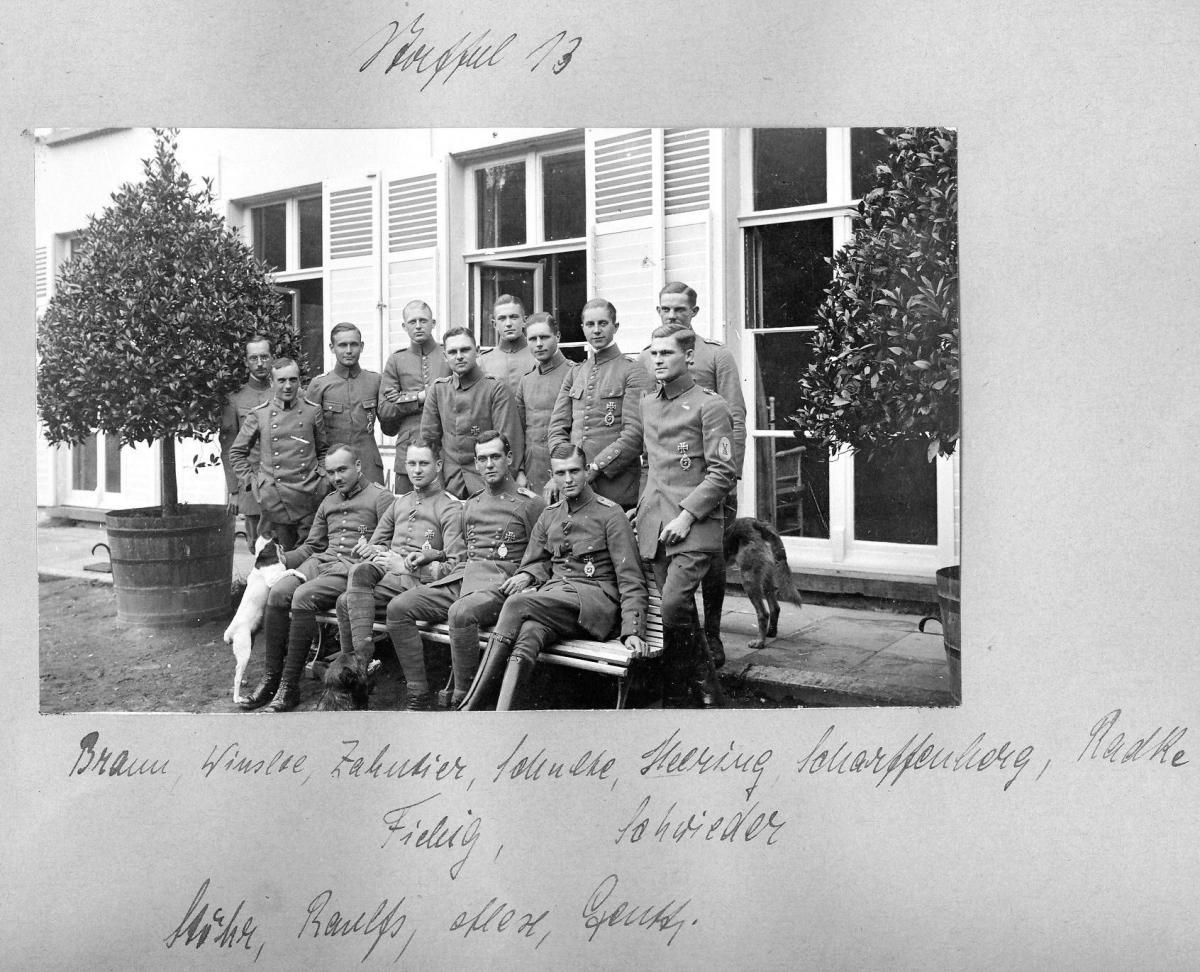

Shulte had originally joined a prestigious Guards Regiment, but had transferred into the Kampfgeschwader der Obersten Heeresleitung more commonly known as Kagohl 3 or the English Squadron. Based in Belgium his squadron’s mission was to fly over the English Channel and bomb targets in London and the South East. The aircraft were twin-engined Gotha bombers fitted with extra fuel tanks for the long journey. The missions must have been extremely demanding: the men were exposed to the elements as they flew at over 80 mph at heights of around 14,000 feet. Indeed the crews were provided with oxygen tanks to supplement the thin air available at these altitudes. This was still in the early days of aviation and missions could be hampered by adverse weather conditions and mechanical breakdown, and then there were Britain’s fledgling air defences to contend with. Indeed Schulte had already been forced to land an earlier mission on the beach at Ostend after his plane was seriously damaged in combat.

In early December 1917, eighteen German bombers succeeded in making the difficult journey to England. Early in the morning Schulte’s plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire on its return flight causing its port radiator to overheat and its engine to catch fire. The plane crashed in a meadow near Canterbury in Kent. The 3-man crew immediately set fire to the aircraft. A group of farmhands approached them and were told in broken English, ‘We German, fetch a constable.’ The bomber crew accordingly surrendered to two local special constables, one of whom was the local vicar.

Schulte was originally imprisoned at Colsterdale near Masham. A young German prisoner’s diary records the excitement felt in the camp when news of his arrival broke. Little is known of Schulte’s time at Skipton. A British officer Lieutenant Gray mentioned his friendship with Schulte which developed when Gray led the more energetic prisoners on some longer hikes into the surrounding countryside. After the flu epidemic had abated the German officers paid for a monument to their deceased comrades at Morton Banks.

The first raid on London by fourteen Gotha bombers in June 1917 was also the deadliest. 162 British civilians were killed and a further 426 injured. A 50kg bomb passed through the three-storey Upper North Street School in Poplar before exploding on the ground floor. Eighteen children were killed: most of them were infants aged between five and six years old. This one raid brought firsthand experience of the harsh realities of war into the lives of many British civilians and served as an unwelcome portent of things to come.

Schulte’s younger brother Paul was a Catholic priest and a very persuasive man too. In 1936 he was able to secure a berth on the very first flight of the airship Hindenburg as it flew from Germany to the United States. At the same time he used the opportunity to gain dispensation from the Vatican to hold the first Holy Mass on the airship. During his return to Germany the Hindenburg flew low over Keighley and dropped an unexpected package on the town. The story was picked up by the British Movietone News. The newsreel feature ‘Hindenburg drops letter at Keighley’ lasts for fewer than 30 seconds and can be found online. The transcript of the short feature read in the clipped vowels of the 1930s reads:

‘Remembrance from the sky. Bearing the Hindenburg stamp and thrown from the airship as she flew over Keighley, Yorkshire, this letter and cross was picked up by two Boy Scouts Jack Gerrard aged 11… and Alfred Butler aged 12. A bouquet of carnations was with the letter, and following instructions the two boys took the flowers and laid them on a grave, the grave of Franz Schultz [sic] a German prisoner of war who died here and whose brother a German priest dropped the letter and bouquet as the Zeppelin passed.’

The Hindenburg was unmistakeable as it made its way down the Aire Valley. At 804 feet in length the giant silver airship was just 78 feet shorter than the Titanic. With a bright red panel on each of its tail fins surrounding a white circle and a black swastika it was equally obvious who was in charge of things back home. Interestingly a number of local people have recently told the author that they remember seeing the Hindenburg as it flew overhead.

People have speculated about the reasons for the Hindenburg’s roundabout route back to Germany. Was it perhaps involved in a covert spying mission across the north of England? According to Paul Schulte’s biographers, the truth is much less sinister. The journey from Germany to America was always difficult battling against the prevailing winds. The return trip with the wind behind the airship was less fraught. Paul Schulte had merely asked the captain of the Hindenburg if it would be possible to fly over West Yorkshire. Permission for the flight was duly obtained from the British authorities. The Zeppelin Company was continually beset by financial difficulties and any publicity it could gain from the return flight might prove beneficial.

In the 1960s Franz Schulte’s body and those of the other flu victims were exhumed and reburied at the German military cemetery at Cannock Chase in Staffordshire. The monument itself is believed to have been bulldozed into the empty space that was left behind.

Paul Schulte dubbed himself the ‘Flying Priest’ and raised money to improve communications between isolated communities. A Pathé newsreel film shows him delivering both pastoral care and badly needed supplies to isolated communities in the frozen north of Canada.

And the Hindenburg? The Hindenburg burst into flames at the end of its flight to Lakehurst New Jersey at the start of the 1937 season. The newsreel film of the conflagration and the eye-witness radio commentary are both dramatic. Amazingly sixty-two of the ninety seven people aboard the airship survived the blaze.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here