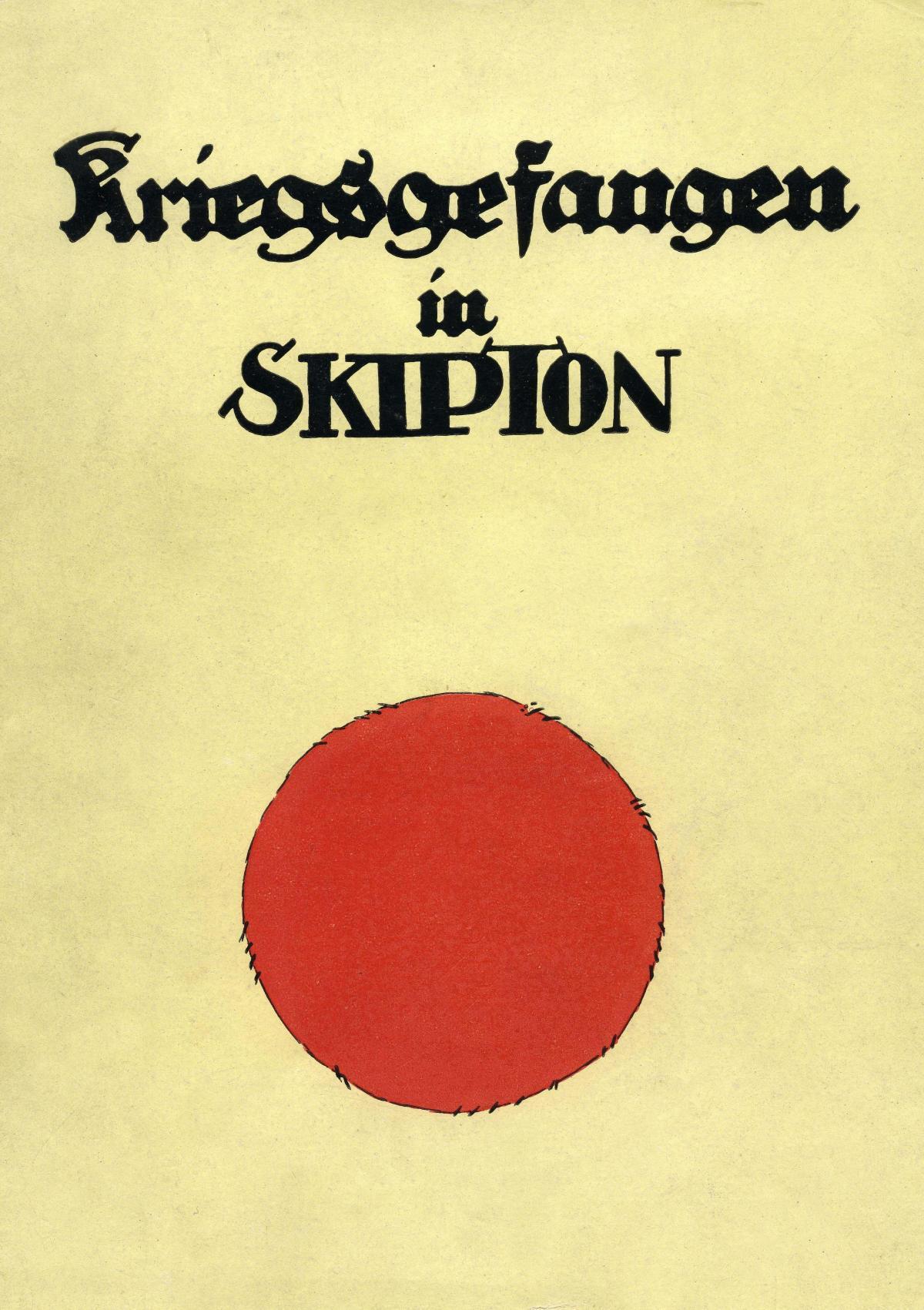

The Christmas celebrations at Skipton's Raikeswood Prisoner of War camp had extra special meaning in 1918 as the German officers waited to hear when they would be released.

From extracts documented in secret diaries written by the prisoners and compiled into the book, Kriegsgefangen, which is currently being translated into English, eight pages were dedicated to the celebrations by Captain ZS Sachsse. They were translated by Alison Abbey and Ada Whitaker who are part of a team led by Anne Buckley, a lecturer in German at the University of Leeds . The sketch is one of the Christmas cards sent from the camp and drawn by prisoner Erich Dunkelgod. The message reads: 'Merry Christmas'.

CHRISTMAS had come around again, the fifth time in captivity for many of us. But this time it had a special meaning: the old Christmas message ‘Peace on Earth’ had at least partly come true; the Armistice had put an end to the war. What the peace would be like nobody could yet imagine. On the contrary! Since the terms of the Armistice were so harsh, peace would surely be all the more bearable. There was hardly anything left that the opposing side had not demanded and been granted. So hope for the peace dawned in our hearts like the promise of spring. The possibility that we might soon go home shone as brightly before our trusting eyes as any shimmering mirage ever appeared to a man wandering in the desert. So this last Christmastime of our captivity was the first we planned to celebrate with unadulterated joy– and we did celebrate! It was the best Christmas that I experienced in England.

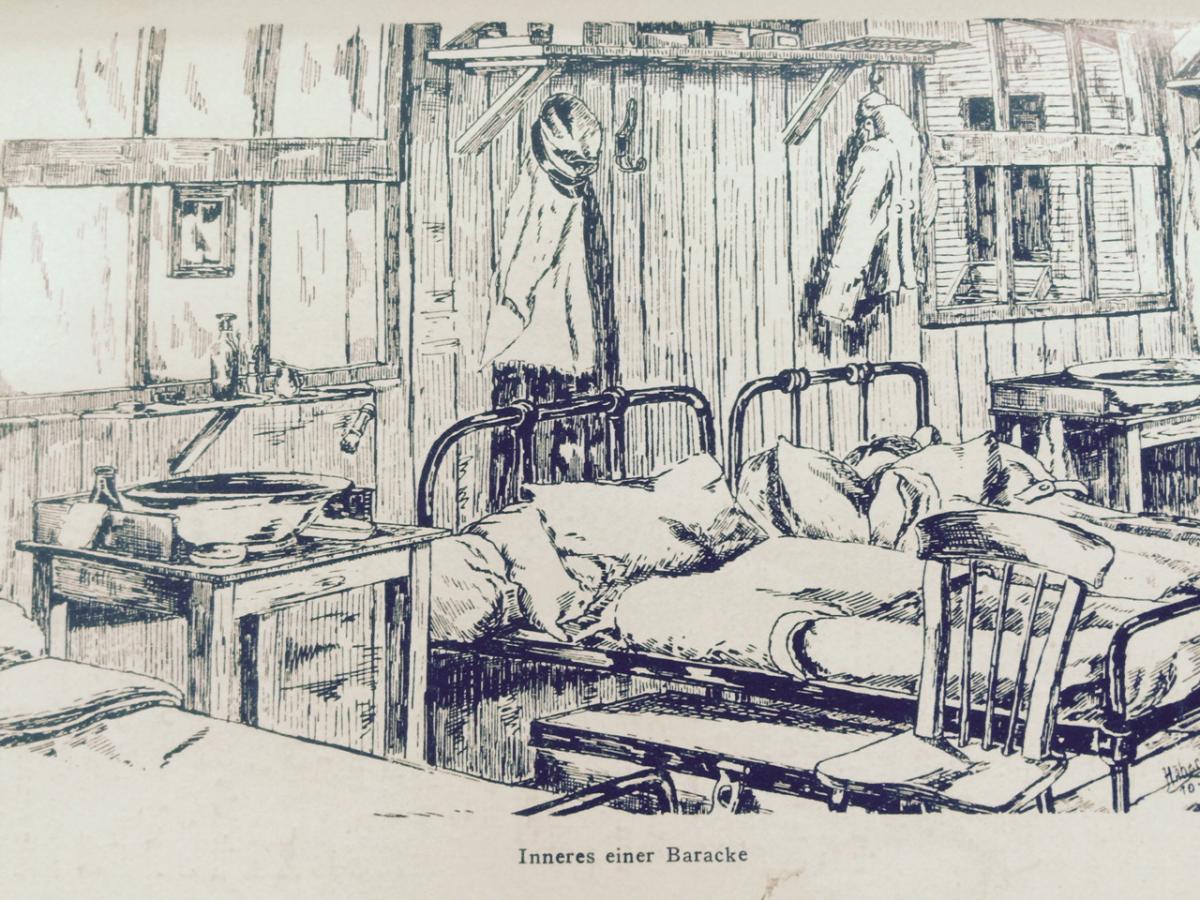

A few days before, a small tree was brought to each of the barracks. Of course, we only had modest means available to decorate them: paper and cotton wool, but nevertheless in the skilled hands of some especially talented men these were crafted into little works of art, and when the green denizens of the forest appeared in all their glory, we could with a stretch of the imagination almost recognise our dear old German Christmas tree whose magic spell, which first enchanted us in childhood, had not, even yet, quite faded away.

It is said that it is hard to study properly on an full stomach, but the reverse can also be argued: it is hard to celebrate on an empty stomach. In view of this important fact the enlisted men’s kitchen had taken steps in good time to address this evil – the constant emptiness of the prisoners’ stomachs. Using their own savings and with a few under-the-counter purchases, on Christmas Eve every man could be provided with a bowl of fried potatoes, and this unusual event of actually having an evening meal did wonders for our mood. When the lights came on, our faces also shone with contentment. Then the sound of our dear old Christmas carols opened up our hearts. It is an old truth that “…out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh” . Our conversation turned again and again to thoughts of home, parents, wives and children. What else should we have talked about on Christmas Eve! Some of us who had been together in the Brocton camp must have remembered the Christmas Eve of 1917, when our Christmas treat consisted of four pickled herrings to be shared between the 40 men in each barrack, and when we sat together huddled in overcoats and blankets, freezing because the Camp Commandant had refused to give us coal. Even this memory made us feel all the more content because the difference between that day and this was so obvious and palpable.

Then came Christmas Day, bringing us a number of pleasant surprises. The kitchen administration and the Camp Sergeant Major seemed determined to bowl us over – and they certainly succeeded. Only someone who has actually been a prisoner in England can really appreciate what a blessing a mouthful of good coffee is after all that tea. And this blessing was conferred on us – and with milk too! There was even cake to go with it, proper cake with proper raisins, properly baked, with proper sugar on top! However much we doubted it, we had to accept the incredible fact that such things actually did still exist. For some however, especially those with families, every bite evoked the sad realistation that their loved ones at home would certainly not have such a festive breakfast. I am convinced that many of us would rather have packed up the whole glorious thing and sent it home. It does not need to be said that the festive mood at the midday meal was enhanced by stew and dessert instead of what we called “bolshevik soup”.

The actual celebration took place in the afternoon and evening of Christmas Day. For this purpose the enlisted men were allowed to use the Old Mess, a large hall-like room, at one end of which rose a mighty fir tree. On long rows of tables arranged in a horseshoe and covered by white tablecloths, 135 cups of festive cocoa steamed invitingly. To our particular delight, the Camp Senior came to join the enlisted men’s celebration. The first part was a typical Christmas celebration. The venerable words of the Christmas gospels spoke more poignantly to our hearts than they might have done in better times; for some of us it may even have been only through war and captivity that they became meaningful at all. So our lovely German carols about the silent, holy night and the happy beneficent time of Christmas rang out strongly throughout the hall. And in his speech, the Sergeant Major put what we were feeling into words: as he spoke we could see, in our mind’s eye, the last few Christmas celebrations, feel once more the burning longing for home that becomes particularly acute at this season, feel also the deep despair that always overcame us with the realisation of the fruitlessness of our wishes, and pull ourselves together once more, determined to face the cold, hard fact that we would just have to bear it. But then the image changed and he painted a picture of home for us brush-stroke by brush-stroke until we could see it before our eyes, with hill and vale, stream and meadow and the little cottage that we call home in which live two dear old people with white hair and work-worn hands, gazing with silent joy at their own strapping lad returned at last from England. And beneath this attractive portrait he added the text: “Soon comrades, this will be reality.” Oh how eagerly we listen to someone talking about home!

Eight comrades who were proficient singers had set up an octet and entertained us with the traditional hymn ‘A great and mighty wonder’ and Beethoven’s ‘Hymn to the Night’. And then came Father Christmas, in costume , with a big sack and a big beard! The beard was false but the sack was real and contained the presents that the officers in the camp had provided for the men. There was something for everybody: some were given pocket knives, tobacco pipes, cigar and cigarette holders, others board games, soap, shaving soap, braces and many other things that brought great joy. But Father Christmas also knew quite well that ‘It is the spirit that quickeneth’ and had inserted a little verse to each package, good-humouredly but aptly mocking the greater and lesser weaknesses of the recipient in language that admittedly was not always suitable for ‘polite society’ and did not always conform to the norms of poetry, but was always comical. Gales of laughter accompanied the ‘proclamation’ of these pearls of German poetry and Father Christmas was quite right to stroke his beard in contentment.

After a break of about two hours the second more general part of the celebrations began, dedicated to merriment. Introduced by a prologue spoken by the poet himself (we counted quite a number of artistic types in our midst), the evening began with a quartet entitled ‘the menu’ and Zöllner’s humorous chorus. Under normal circumstances the tempting abundance of this menu would have made our mouths water, but that day’s never-ending stream of pleasures for both body and soul had dulled our senses a little so that most of us limited ourselves to the observation, sometimes spoken out loud, that there must have been some underhand dealings going on. An ‘original Viennese Schrammelband’, consisting of two violins and a guitar excelled in a colourful series of ‘classical’ pieces, alternating with a variety of solo performances both serious and light-hearted. There was even a woman on stage! Fake, of course like Father Christmas’ beard, but still a welcome sight for our eyes accustomed as we were to only seeing men. Now and then the hall resonated with the heavy stamping of a schuplattler folk dance group performing their ‘national’ dance with all the elemental energy of Upper Bavaria. But it was most probably Töpfer who was the greatest success with his comic turns with some expressions that later became proverbial, and secondly our little ‘Liebknecht’ with his gripping performance: I am down and out (in a Berlin accent) – as if we needed to be told. We would have known this just by looking at him.

So the evening passed in the most cheerful of atmospheres. The bell for lights out rang all too soon. ‘Let’s hope it was for the last time!’ With this hope we went our separate ways to seek our usual solace in dreamland for the harsh realities of days past and to come.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here