Government fund- raiser Lord Levy has been arrested and questioned by police. Cabinet Ministers have been sacked for incompetence and demoted for immorality. Councillors have been jailed for corruption and charged with sex offences all this and more. Can politicians be trusted? JIM GREENHALF reports It is a measure of how amazingly uncynical the public is that whenever a politician stands on high moral ground and denounces sleaze and corruption, his popularity rating soars.

Tony Blair did this in 1997 after Labour's landslide General Election victory. The Prime Minister talked of the privilege of public service, the voters' bond of trust, the necessity of Labour politicians to be "whiter than white".

John Prescott regularly bashed John Major's Tories for the sexual escapades of some of its members and the lust for cash in brown envelopes in return for Parliamentary favours.

But within a year of Labour's election in 1997 stories were running about Bernie Ecclestone, Formula One motor racing multi-millionaire, giving Labour £1m and the Government's reluctance to ban Formula One sponsorship by tobacco companies.

The year after Labour's third consecutive General Election victory, the Prime Minister himself is to be questioned by police about the alleged sale of House of Lords peerages in exchange for large donations to Labour Party funds.

And for what seems like forever, Deputy Prime Minister Prescott has been hounded by the media for peccadilloes committed in and out of his numerous grace and favour residences.

The T&A revealed how disgraced Bradford Conservative councillor Intikhab Alam still claimed and pocketed expenses despite being jailed after killing Christopher Benson in a hit-and-run incident last May.

His Tory colleague Khadam Hussain received more than £11,000 even though he was obliged to resign from Council a few weeks before the end of the financial year.

Hardly examples to inspire confidence among the young and impressionable, especially those sceptics doubtful about democracy's morality.

And then there is the incredible mess of the Council's £1.2 billion Asset Management Project selling off the management of theatres, museums, parks and other amenities which was suspended last year following allegations that there had been mismanagement of the bidding process.

In March the Audit Commission, brought in to investigate, issued a report which stated that top managers had failed to follow proper procedures and keep records of an important meeting.

The Council has spent up to £3.75m already on this doomed project and could yet be obliged to spend another £3m of council tax payers' money on a lawsuit.

Cynics who doubt the efficacy of examples set at the top will say that local and national politics have nothing to do with a duty of public service; politics is just a career move, a gravy train with rich rewards salaries, index-linked pensions, expenses, travel concessions.

Either we are hopelessly gullible and therefore susceptible to plausible promises, or there is something in us that yearns for truth, self-sacrifice and a degree of nobility among our public figures.

Perhaps both propositions are true. In which case the scandal known as Donnygate should tell us a lot about the contempt for public trust inherent in some councillors and highly-paid officers.

In what was the biggest police investigation into local government corruption, 31 people connected with Doncaster District Council were convicted of various corruption offences including no fewer than 25 Labour councillors.

A property developer was sentenced to five years for corrupting Doncaster councillors connected with planning. A planning chairman got four years for accepting a £160,000 farmhouse as a bribe for planning permission. A deputy leader of the council got two years for accepting gifts and cash totalling more than £30,000.

Author Ron Rose, writing for political magazine Red Pepper, says: "Alongside a relentless variety of expenses fiddling (travelling second class, claiming first class, travelling in a car and claiming individual train fares, claiming extra nights accommodation or inventing non-existent conferences) was the £60m which went to developers who bought land cheap, gained planning permission from paid stooges on the council, and sold on or developed for huge profits."

Corruption, funny goings-on, sharp practice however you define it has been a public feature of local government since the Poulson scandal in the early 1960s.

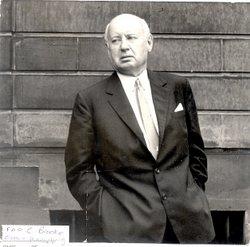

John Garlick Llewellyn Poulson was the head of a huge firm of architects in Pontefract. He was jailed for seven years in 1974 at Leeds Crown Court for bribing local authority officials and politicians in return for lucrative contracts.

Although mainly associated with the North East and T Dan Smith, Poulson's company also secured work in Bradford, playing a part in the creation of the Arndale House office block in Charles Street, drafting the original design for the Kirkgate Centre as well as designing Tong and Cavendish schools.

Among 20 people who appeared in court on corruption charges were former Bradford Lord Mayor, Alderman Eddie Newby, and former Bradford City Council architect William Brown and his secretary Mary Fenelon, who all received suspended sentences.

In the past year or so the shadow of ill repute, and in some cases criminality, has fallen across at least nine Bradford councillors or former councillors: seven Conservatives, one Liberal-Democrat and one BNP.

These cases give rise to questions about the moral fibre of candidates, selection procedures and the vigilance of local parties in making sure that elected members understand the rules governing public behaviour.

Election procedures may lack transparency, but recent events indicate that problems start after councillors and MPs are elected.

Strong public figures with weak personalities are vulnerable to temptation.

John Poulson, who died in 1993, was a religious man with strict moral views about right and wrong except where his own business ambition was concerned.

He was also surrounded by weak and greedy public officials who between them accepted gifts and bribes worth £500,000 a colossal sum in the early 1970s.

Former T&A deputy news editor Ray Fitzwalter and David Taylor in their 1981 book about Poulson, Web of Corruption, attribute the scandal not just to human weakness but Britain's culture of secrecy, the lack of open government.

The Inland Revenue's Inquiry Branch knew about Poulson's corruption but declined to pass the information to the police because the IR placed a higher value on the duty to maintain confidentiality.

Donnygate is testimony to that. Ron Rose concludes: "When the Poulson scandal was at its height, civil servants looked hard at the problem and realised that in order to cleanse local government they would have to cull a substantial proportion of those people who were active in public life.

"So the investigations were closed down instead, and a culture which believed councillors to be poorly-paid heroes whose devotion to the public good excused the occasional bit of pilfering, or that the nod and a wink progress of selected planning applications was all part of the regeneration strategy, was allowed to develop into the brazen criminality of Donnygate."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article