With one-in-five children in Bradford growing up in a household where no-one works, an ongoing cycle of poverty and under-achievement is almost inevitable.

This week, a Prince’s Trust survey revealed that 23,000 children in the city – higher than the regional average – are growing up in a jobless family, leaving them trapped in a ‘cycle of worklessness’.

The charity warns that they are more likely to end up unemployed than youngsters whose parents work.

The report, Destined For The Dole?, released by the Prince’s Trust and Qa Research, says youngsters whose parents don’t work are twice as likely as their peers to feel they lack confidence, skills or talents.

Nationally, there are 1.9 million children in jobless households – the highest number in the EU.

Samantha Kennedy, Prince’s Trust acting regional director, says it’s “a tragedy” that so many young people “feel condemned to a life on benefits”.

She adds: “Only by giving young people skills, confidence and positive role models can we help them break out of this unemployment trap.”

With more than one-in-three youngsters claiming they have no-one in their community whose careers they respect, the role model issue can’t be ignored.

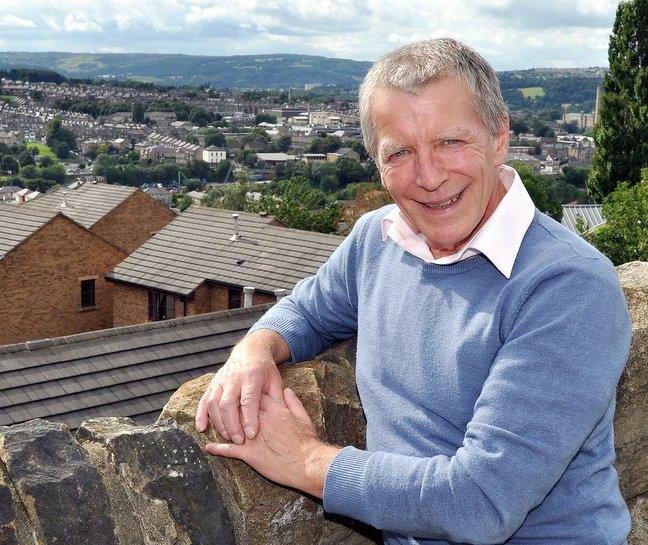

Youth worker Gerry Hannah is founder of Frizinghall-based Parenting Together, which puts parents in touch with agencies helping young people and families. Gerry believes young people end up jobless because of a “culture of underachievement” and a lack of appropriate role models.

“Youth unemployment is a cultural and social problem, rather than a family problem,” he says. “There is a culture of underachievement, affecting working-class young men particularly, which restricts their life opportunities. Their role models are gangsters with money.”

He says many of them grow up resentful of achievers. “They’re frightened of being exploited by their peers, which is what happens if they get a job. It’s such a waste of potential,” says Gerry. “They grow up thinking that to survive and be an adult provider, you have to know all about the benefit system the legal system and crime. It’s very hard to break out of that. “In other countries, young people grow up striving to be better providers than their parents, but we don’t have the same rites of passage.

“In Sweden, there’s a town the size of Keighley which has 27 youth organisations. Keighley has about five. Young men don’t have adequate role models in this country because men have become afraid to take on caring roles, bringing them into contact with children and young people.

“Young people need to be shown equality between men and women. Men should be encouraged to work in primary schools and as youth leaders, showing young people the way in terms of caring for others.”

Gerry says parents and schools have a role in creating a caring ethos: “Parents must take responsibility, and fathers should have more interaction with their children. And at school the emphasis on the first couple of years should be on socialisation – teaching children to respect and care for each other – rather than literacy and numeracy.”

Next week, on the Buttershaw and Canterbury estates, a group of young people are highlighting the reality of growing up in jobless families in a drama they’re devising. It’s part of Save the Children’s Shout Out projec,t working against child poverty. Youngsters will perform their drama, which explores unemployment, education and crime, in their community.

Richard Dunbar from Save The Children says: “Providing more help for childcare costs and helping to make work pay better, by allowing more parents to keep their benefits when they take up work, will help parents take up jobs. It will also help parents stay in work if their job fits around their family commitments.”

Richard says the link between poverty and educational achievement also needs to be addressed: “It is unacceptable that the poorest children are almost three times less likely to leave school with five good GCSEs than their richer peers. Save The Children argues that, to put this right, the Government has to target extra money at the poorest pupils so schools can afford extra one-to-one lessons and smaller class sizes, helping children do better with schoolwork.

“We also want the Government to set up services for poor parents, so they get the support they need to give their children encouragement and advice to do better at school.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel