Manningham has a reputation as a run-down area with social problems.

But Trevor Mitchell, regional director of English Heritage, says: “Forget stereotypes. Bradford is one of England’s greatest stone cities and Manningham perhaps its finest district.”

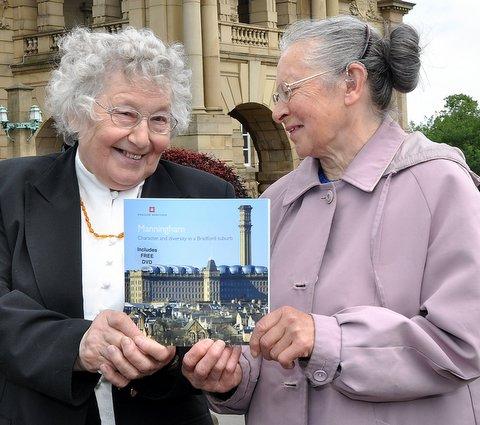

He was speaking at the launch of English Heritage’s latest project, a book about Manningham’s buildings – Manningham: Character and Diversity in a Bradford Suburb – and a DVD featuring Manningham people.

In the thick of the Industrial Revolution when the hollow of central Bradford was like the bowl of a pipe, belching smoke and sparks, Manningham Lane was the main northern thoroughfare.

It was tree-lined and cobbled; elegant black gas lamps flanked the road. Towards the Lister Park end were the more elegant villas, squares and crescents where the better-off lived.

Clifton Villas features in Howard Spring’s novel about the rise of the Labour Party, Fame is the Spur. For six years Lord Kagan, textile manufacturer and friend of Prime Minister Harold Wilson, lived at number 4.

Manningham’s transformation from a rural backwater to an industrial suburb can be seen on two maps that bookend English Heritage’s book.

At the front, Manningham is a patchwork of fields and open spaces, much as it had been in 1379 when only 19 adults were registered on the poll tax return. That changed dramatically with the development of factories and railways in the 1830s and 1840s.

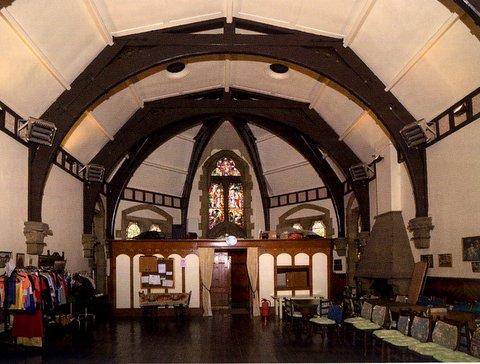

Turn to page 107 of the book and the spaces and fields have become grey blocks separated by a white ribbonwork of roads and streets, churches and mosques, converted textile factories, curry houses, shops, schools, large houses, a park, a grammar school and a professional football club.

There are 11 maps in the book, which also includes eight coloured illustrations and 93 photographs, only six of them showing people. The ‘character’ and ‘diversity’ on the title page refers principally to buildings and locations.

Some of these fine buildings are at “crisis point” – the former police station on Church Street, and Bradford Children’s Hospital are examples. The early 17th century Old Manor House – remodelled in the 19th century – on Rosebery Road looks in need of a new lease of life.

The book, the 23rd in English Heritage’s series on conservation areas, may be an eye-opener for those who only know of Manningham from the Bradford City Fire Disaster, the Yorkshire Ripper, the summer riots of 1995 and 2001 and the modern controversies of drugs and prostitution highlighted in television dramas such as Band of Gold.

What leaps off the glossy pages is the beauty of the mainly Yorkshire Sandstone houses and villas. Apsley Crescent, Southfield Square, Hanover Square and Peel Square have seen better days; but the pale yellow glow of the locally-quarried stones on sunny sky-blue days remind us that Bradford’s greatest cultural glory is architecture.

The book’s authors, Simon Taylor and Kathryn Gibson, say: “Manningham’s varying character can be traced in part to the actions of a few wealthy individuals and in part to its collective – often mutual – effort of many lesser citizens.

“At its height, Manningham was regarded as Bradford’s premier residential suburb. It was the ‘best end of town’ and a byword for status, style and exclusivity…”

William Andrews and Joseph Pepper, designers of the Register Office and the now defunct Theatre Royal, designed the 27-acre Lister Mill which, for the best part of a century from 1873, manufactured imitation sealskin, mohair, velvet, silk, crepe, chiffon, Crimpelene and Terylene. Lister’s provided material for King George V’s 1911 Coronation and in 1967 curtains for the White House.

After the mill shut down, years of failed plans and neglect followed, until local people rallied to campaign for the building and then developer Urban Splash converted most of the former industrial space into flats.

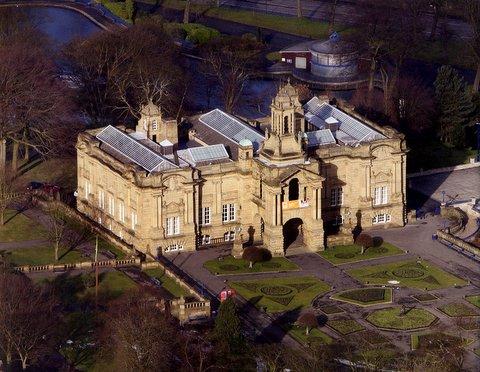

Victorian Bradford had a policy of employing locally-based architectural partnerships. But for Cartwright Hall a Londoner, John W Simpson, got the commission.

Manningham also has examples of contemporary excellence such as the £4m facelift of Lister Park, including the stylish lakeside boathouse, designed by Bradford Council architects, and the refurbished Cartwright Hall art galleries and grounds.

In living memories

On the DVD accompanying the book is Betty Hurd, 80, who recalls the sound of Lister Mill when it was a working factory.

She said: “I remember the noise of hundreds of feet going over pavements to the mill. And when the hooter went for closing – you could hardly cross the road without being run over.

“The mill was such a part of Manningham and it was very sad when production stopped.”

Manningham, like Bradford, has a reputation for absorbing foreigners. Polish sisters Helen and Olga Klimach are two of them. They came to Bradford in 1955.

Olga said: “Our best outings were to Lister Park. There were nice green houses there with nice big plants. Young children used to knock the plants over, so we had to run.”

Helen said: “There used to be a swimming pool in Lister Park. Everyone admired this because it was a sun trap. But you had to pay to get in.”

Their children, Olga added, got round this by getting in over the back wall.

Happy days.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel