AS a teenager growing up in Bradford, I often felt drawn to the ‘top of town’, especially the stretch of Westgate between what used to be the old Morrisons store and the start of Lumb Lane.

I was fascinated by the Victorian shops lining the opposite side of the road, aided by several good independent record shops where I’d spend my free time browsing for bargains. In my later years, the New Beehive Inn a little further up became a regular haunt and my favourite Bradford pub with its beautiful original interior and iconic gas lanterns.

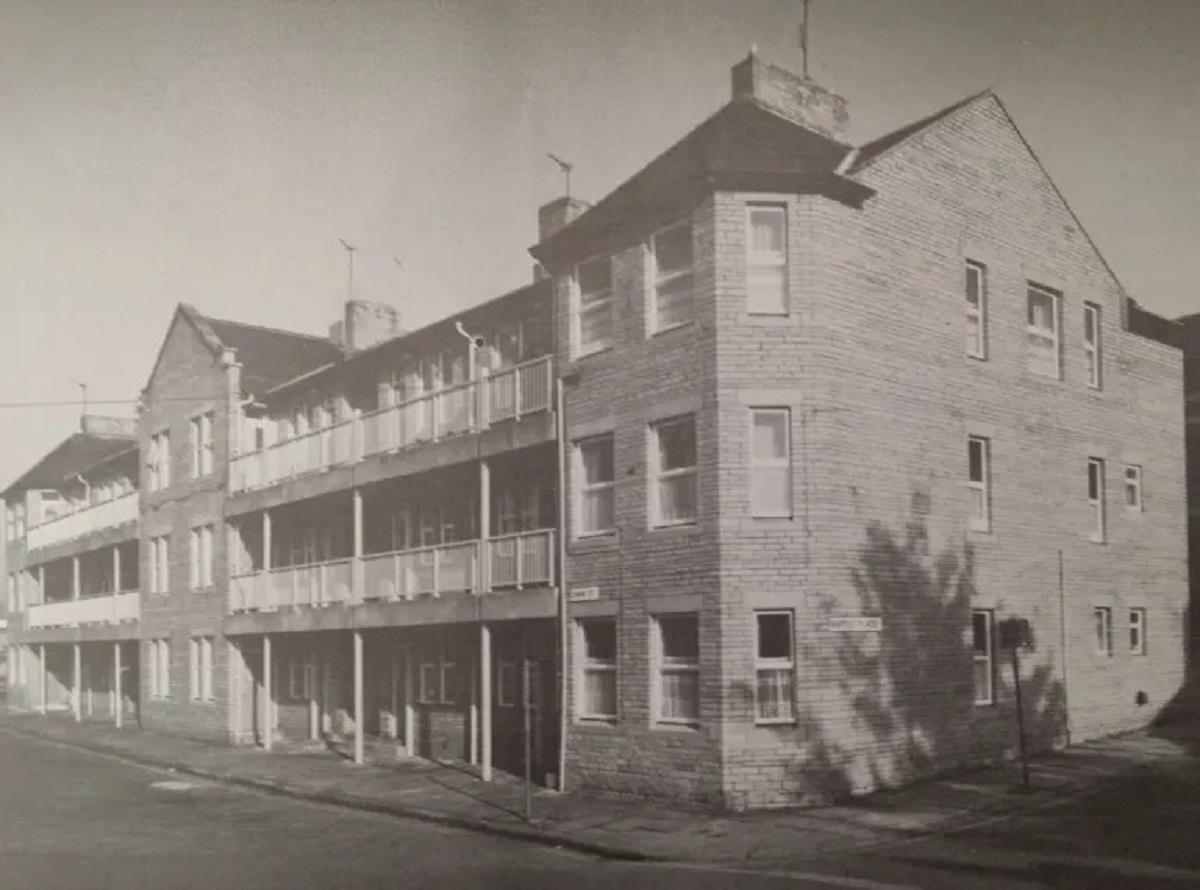

Of equal fascination were the tenement blocks tucked away behind the shops on Westgate. Whilst obviously built for social housing, and certainly at the time looking to have seen better days, their style was radically different from anything else I’d seen in Bradford, and I knew there had to be an interesting story as to why they were there. This curiosity led me to spend many hours in the reference library, searching for anything mentioning this area, looking at old maps and trying to piece together what had led them to be built.

The story of Longlands, this unique site on the north-western edge of the City Centre, is one of the most important in the history of modern Bradford and arguably had a direct impact on its housing policy in the 20th Century. It certainly ranks alongside Margaret McMillan’s efforts for children and education in terms of social progress, but most people wouldn’t have any idea if you were to ask them where Longlands is.

Back in the late 19th Century, it was one of several ‘lost’ neighbourhoods circling Bradford town centre, including Broomfields, Wapping, New Leeds, White Abbey, and the George Street area. Like its counterparts, Longlands was made up of densely packed back-to-back terraced housing with cobbled streets, small courtyards, and little in the way of sanitation. Unlike most of our neighbourhoods today, each of these had far more amenities including butchers, greengrocers, bake houses, pubs, and blacksmiths. Many of the properties were not structurally sound and practically all were owned by private landlords. The population density was huge with over 250 people per acre and typically four families per house, many sleeping on floors. Infant mortality rates were high as was disease and crime. It was often remarked how safer it was to drink beer than the local water.

In response to concerns about these conditions, Frederick Jowett, the first Independent Labour Party councillor elected to Bradford Corporation, took it upon himself to press for the local authority to use its powers under the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890. This allowed a council to declare an area ‘insanitary’ and obtain compulsory purchase powers over the affected properties, demolishing them and replacing with purpose-built social housing. Jowett felt that Longlands was particularly bad and using his position as Chair of the Health Committee he was able to begin a public inquiry led by Bradford’s Medical Officer, W Arnold Evans.

Evans described Longlands as ‘a festering sore’ on page 1 of his final report and recommended the area be declared ‘insanitary’ under the Act for improvements to be made. Despite the clear-cut nature of this fact and a housing scheme being presented, internal opposition in Bradford Corporation, mostly from Tory landlords on the Housing Committee whose properties were to be demolished, held matters up for some years until finallyby the turn of the 20th Century an agreement was reached. By 1909, the area had been rebuilt with five tenement blocks erected (only three of which survive today) with a design influenced by the Garden City Movement. In 1914, the estate was further extended.

Of course, the residents of Longlands needed to be moved elsewhere for their neighbourhood to be cleared and rebuilt. To that end, the Faxfleet estate, in between Marshfields and Odsal Top, was created. It is worth noting there was a lot of opposition from the residents themselves, predominantly Irish Catholic, of being moved so far away from their places of work as well as a feeling they were being singled out because of who they were. The Irish heritage of Longlands is reflected in the Harp of Erin pub that was built as part of the new estate, St Patrick’s Catholic Church which remains today and the fact that, for many decades, the area was served by the City’s Irish Club.

And so, with the restoration of Longlands, a model was set for further slum clearances in Bradford. Whilst this process was interrupted by the two world wars, new estates were created further out of the city to temporarily relocate the populations of inner-city areas needing demolition and resurrection, for instance the Canterbury estate built to relocate the residents of Broomfields. One by one, these old neighbourhoods have either now gone or been radically changed and most of their names are no longer commonly used.

And such is the issue with Longlands which is often mistakenly called ‘Chain Street’ or ‘Upper Goitside’. Its name should be preserved and indeed celebrated for its significance in the social progress of Bradford in the 20th Century.

l Jonathan Crewdson is the Director of the Neighbourhood Project CIC which campaigns to promote community identity and resident-led action. A talk on the history of Longlands will take place on Friday, February 25, 4pm-6pm, at the Millside Centre, Grattan Road. Anyone wishing to attend must first book by emailing mail@neighbourhoodproject.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel