MARTIN Greenwood writes:

BRADFORD’S history has been marked by occasional civil disasters that have captured the headlines. All Bradfordians over the age of 50 will have their memories of the worst disaster of all at Valley Parade, where 56 people died and 265 were seriously injured by the fire that destroyed Bradford City’s main stand on May 11, 1985. Since then the story of the fire has been much written about and filmed. Bradford City rose like a phoenix to reach the Premier League in 1999.

However, some earlier, but none the less tragic, disasters are less well known. I have selected three each linked with a prominent Bradfordian of his day whose legacy was shaped overnight by the disaster. Each story had a quite different outcome.

We start with the disaster in 1871 when a prominent factory owner learnt his mill was on fire and his life’s work was in danger. At 11pm on February 25 flames were seen coming out of a window in Lilycroft Mill. It was Saturday evening with few people about.

Let the Bradford Observer take over the story: ‘Before 11.30pm it had found its way through the roof like a huge furnace, and a great column of light smoke rose above. The ravages which the fire was making inside were long shown by the emission from various windows of large sheets of flame which extended several yards beyond the walls. A little after 11.30pm the roof of the warehouse fell down with a great crash, and an immense volume of fire rose at least twice the height of the building.

The conflagration could be seen for miles around, and great numbers of people continued to crowd to the spot. The road was filled with an eager multitude, and hundreds of anxious faces might easily be distinguished in the awful sight before them. Women were wringing their hands and bewailing, while men living in the adjoining cottages hurried their bedding and furniture into the street in anticipation of the speedy destruction of their homes.’

The alarm was raised at nearby Manningham Police station where they had a small fire-engine which proved totally inadequate to quell the fire. (When Bradford was made a municipal borough in 1847, the new Corporation had appointed a new Chief Constable and made him responsible for handling fires!).

A messenger also went down to the central police station in Bradford, but a chapter of problems meant that the much larger engine was far too late on the scene, by which time the warehouse roof had crashed down. As the fire started to die down and the hundreds of people who had gathered were drifting away, the damage had become extensive and sadly two men had died.

Samuel Cunliffe Lister (1815-1906) arrived from his home in Addingham to survey the damage the next morning. Not everything was lost - some valuable technical drawings remained. The cost of the damage was £70,000 and he was insured for £40,000. He had invested greatly in the mill, but he seemed to have little hesitation in building a new and much larger replacement. Aged 55 and already a very wealthy man, he retained the energy and motivation to undertake this huge challenge.

Lister came from a wealthy mill-owning family of Addingham. His father, Ellis Cunliffe Lister, a prominent magistrate, operating from his public house, Lister’s Arms (later Spotted House) in Manningham, was elected one of Bradford’s first two MPs in 1832. The family owned Manningham Hall in the nearby estate that became Lister Park.

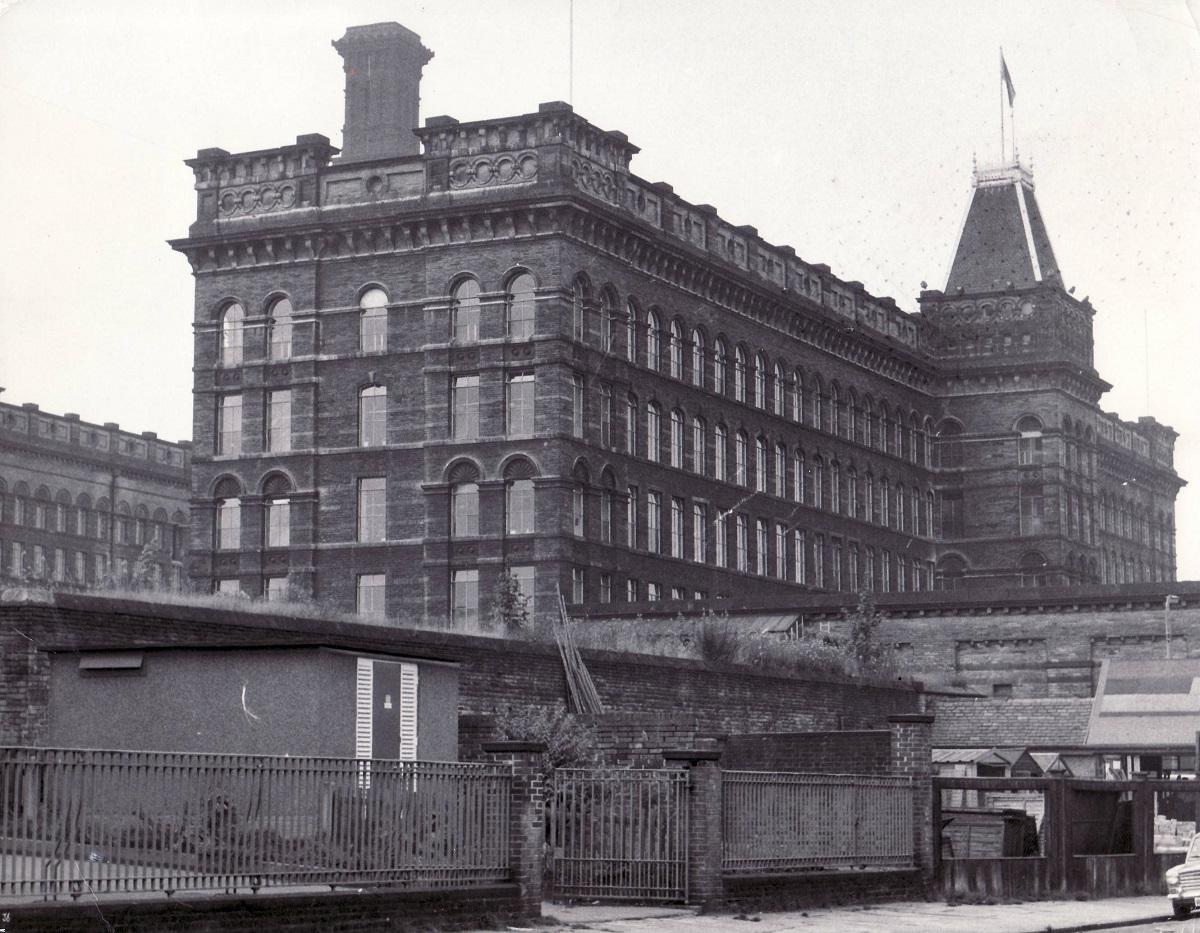

In 1839 Ellis Cunliffe Lister invested in a new mill on the corner of Lilycroft Road and Heaton Road for his two sons in partnership, John the eldest son and Samuel the third son (the second eldest died in 1833). Three years later John retired, leaving Samuel running the business. By 1871 Samuel Lister had a large fortune by mechanising woolcombing at Lilycroft Mill, by then probably the largest factory in the country. Despite a life’s work destroyed in a few hours, Samuel Cunliffe Lister had the resources and character to turn disaster into an opportunity and make another even larger fortune. Within two-and-a-half years his new Manningham Mill (Lister’s Mill) opened with the tallest chimney in the city, 225 ft high built in the style of an Italian campanile. His new fortune was built on silk and velvet. He was the largest benefactor of the new Children’s Hospital opened in 1890. He sold Manningham Hall and estate at well below market rate to the Corporation on condition it became Lister Park for the public. He bought a great estate in Swinton, North Yorkshire. He was ennobled as Lord Masham. He financed the Cartwright Hall Art Gallery which opened in 1904. He died one of the wealthiest men in England.

Despite these achievements, history also remembers him badly for taking on his workers by imposing 25per cent wage cuts when new tariffs on exports were made. They went on strike, but he completely defeated them. The 1890/1 Manningham Mill Strike did not make him popular and became a significant factor in the rise of the Labour Party

Today, wherever you view Bradford from afar, from Baildon Moor to the north or coming off the motorway from the south, the skyline is dominated by Lister’s famous chimney, nicknamed with some justification Lister’s Pride.

* Nearly 150 years after Lister’s Mill was built, the chimney will come to life on March 3,4 and 5 when a large-scale projection will relate stories of Manningham’s past and present. As reported in the T&A, ‘The Mills are Alive in Manningham’ will illuminate the historic site with music, audio recordings, photographs and moving images.

* Martin Greenwood’s book Every Day Bradford provides a story for each day of the year about people, places and events from Bradford’s history. Available online and bookshops including Waterstones and Salts Mill.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel