SIR Titus Salt was a highly successful Victorian manufacturer who helped to make Bradford ‘worstedopolis’, the textile capital of the world. But what was the secret of his success?

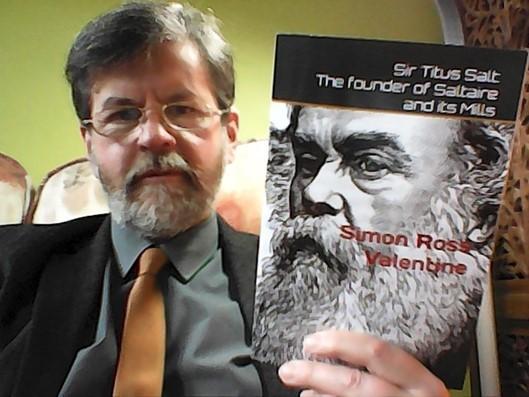

In a recent booklet published by the Ecclesiastical History Society I have attempted to answer this and other questions about Titus Salt.

Born in Morley in 1803, Salt arrived in Bradford at the age of nineteen, where, after an apprenticeship at a local Mill, he joined his father in the firm of Daniel Salt & Son, woolstaplers.

A turning point in Salt’s career occurred in the 1840s when he became the pioneer of alpaca, a long-fibred wool, imported into Britain from Peru. On a visit to Liverpool Salt had come across a quantity of alpaca lying unwanted in a back-street warehouse.

Although advised by other businessmen to have 'nothing to do with the nasty stuff', Salt, unperturbed and innovative, purchased and processed the alpaca, amassing a significant fortune in the process. Salt also successfully experimented with donskoi wool from Russia; and mohair, the wool or hair of the Angora goat.

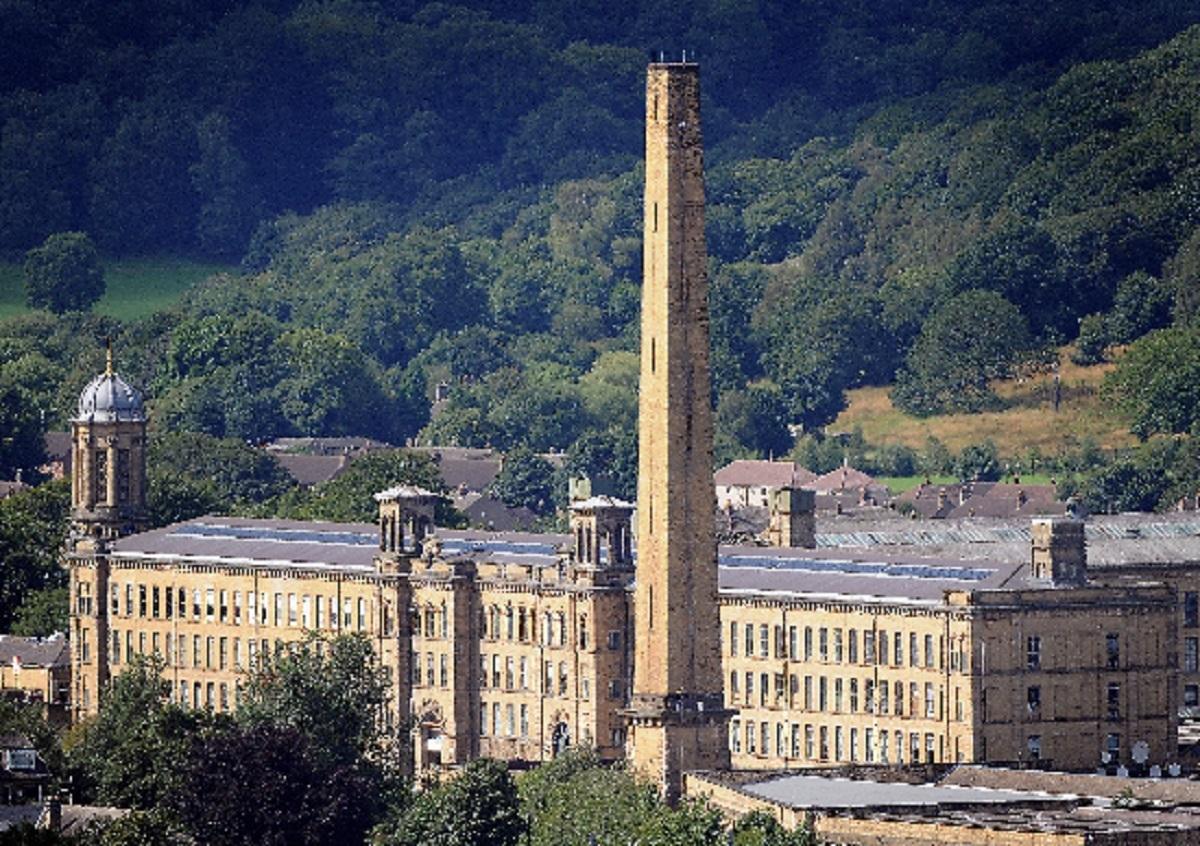

In the early 1850s Salt decided to amalgamate his five existing mills into one enormous building adjacent to the Leeds-Liverpool canal and the River Aire. Designed by the celebrated architects Lockwood and Mawson the south front of the mill is 545 feet in length, the same length of St Paul’s Cathedral and is 72 feet high, with six storeys.

The technology used by Salt in this mill was state-of-the-art. The steam engines, ‘considered a marvel of ingenuity and skill’, were connected to 14 boilers each averaging 50 horse-power, turning shafting to drive the machinery, about three miles in length.

To dissipate the considerable steam generated by these boilers, a chimney was constructed, almost 250 feet high.

In many ways Salt was forward-thinking, willing to spend considerable amounts of money to make his mill - with good ventilation, heating and lighting - a safe place to work in. He added an infirmary to cater for those injured in the workplace and provided pensions, and a sickness insurance scheme for his workers.

Salt was one of the first Victorian entrepreneurs to organise the ‘work’s trip’, taking workers by train on days out to beauty spots in the Yorkshire Dales.

Between 1851-1875, Salt built a model industrial village of 850 houses - Saltaire - for his workers and infrastructure including a park (Roberts Park), hospital, school, washing house, Turkish bath and Churches including what is today Saltaire URC. Almshouses were erected on Victoria Road, 45 in all, ‘for the aged and infirm’.

As well as being the successful ‘enlightened Victorian capitalist’, Salt served in almost every public position in Bradford including Chief Constable of the Manor in 1841-2; senior alderman1847-54; and Lord

Mayor in 1848-49. Salt, the ‘Grand Old Man of Bradford Liberalism’, enjoyed a brief political career as the town’s Member of Parliament from 1859-1861.

However, while studying for a PhD, and lecturing on Yorkshire Nonconformity at the universities of Bradford and Leeds, I was surprised to find that the majority of recent writers on Salt shied away from discussing religion although Salt was a deeply religious man.

In this booklet I have argued that the secret of Salt’s success was his deep Nonconformist faith, particularly his Calvinistic beliefs.

Put simply Salt, a staunch member of the Horton Lane Congregational Church, was a mild Calvinist, that is he believed that God had chosen the Elect, only a small number of people for salvation. As such Salt had to prove his election by being successful in life.

Religion, however, not only motivated Salt to succeed in business but, believing that wealth brings responsibility, it inspired what Balgarnie (one of Salt’s earliest biographers) called his ‘noble spirit of benevolence’. Salt used his wealth in numerous acts of philanthropy in Bradford and elsewhere including local hospitals, orphanages, the sponsorship of St George’s Hall, Peel Park and, unbeknown to many people, the Royal Albert Hall, in London.

The booklet, although acknowledging Salt as an enlightened reformer, considers controversial aspects of his life such as the use of children in the mill and his banning of unions.

The idea of Salt as being anti-drink is rejected as apocryphal. Salt banned pubs in Saltaire because he disliked drunkenness (and of course he wanted punctual sober workers), but did not ban alcohol per se. He allowed the sale of alcohol in the village store. His father had possessed a substantial cellar of wine; and Titus himself similarly enjoyed his daily tipple.

My emphasis also in the booklet is to stress that Salt, although exceptional was not unique, as other local manufacturers built massive mills and houses for their workers. I make mention of Ackroydon in Boothtown, Halifax; Lister’s Manningham Mills and Ripleyville the model village of Henry Ripley in Bolling now almost totally demolished and little known.

Salt’s Mill, which stopped operating as a textile factory in the 1980s, was purchased and developed by Jonathan Silver a local entrepreneur, and now contains cafes, a book shop, rented office space and an art gallery exhibiting the work of local artist David Hockney. Twenty years ago, in recognition of Salt’s industrial achievements at Saltaire the area, including the village, mills and park, was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

I would encourage people to come and see for themselves the grandeur of Salt’s Mill and Saltaire. The booklet is an informative guide and introduction for such a visit. As Susan Roe, galleries and bookshop manager, at Salts Mill remarked: "Simon's booklet places Titus Salt and his achievements in the context of social and religious attitudes in Victorian Britain. It highlights his significance as an important catalyst in Bradford's industrial heritage, the evidence of which lives on and is much appreciated by all who visit Salts Mill."

*Titus Salt: The Founder of Saltaire and its Mill, is on sale at Salts Mill and Amazon, £5.99

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel