PERHAPS partly in recognition of the prowess of Hey’s Ladies, Bradford was becoming something of a centre for women’s football.

The inaugural meeting of the English Ladies FA had been held in the city in 1921 and Bradford had been selected to host the 1922 English Ladies FA Challenge Cup Final. However, a suitable ground could not be found and the final had to be relocated.

The difficulty in finding grounds in the wake of the FA ban on women playing at football league grounds was illustrated when in March 1922, Bradford Rugby Union Football Club applied to the Yorkshire Rugby Union to host a game between Hey’s Ladies and a French touring side. James Miller of Leeds opposed the application, saying that football was not suitable for women, and when they tried to play it they made a ridiculous exhibition of themselves. He was supported by the Rev Huggard of Barnsley who said that ‘they respected and loved their women, and therefore ought not to encourage them to do anything derogatory to their position, or anything that would be unseemly’. The application was refused.

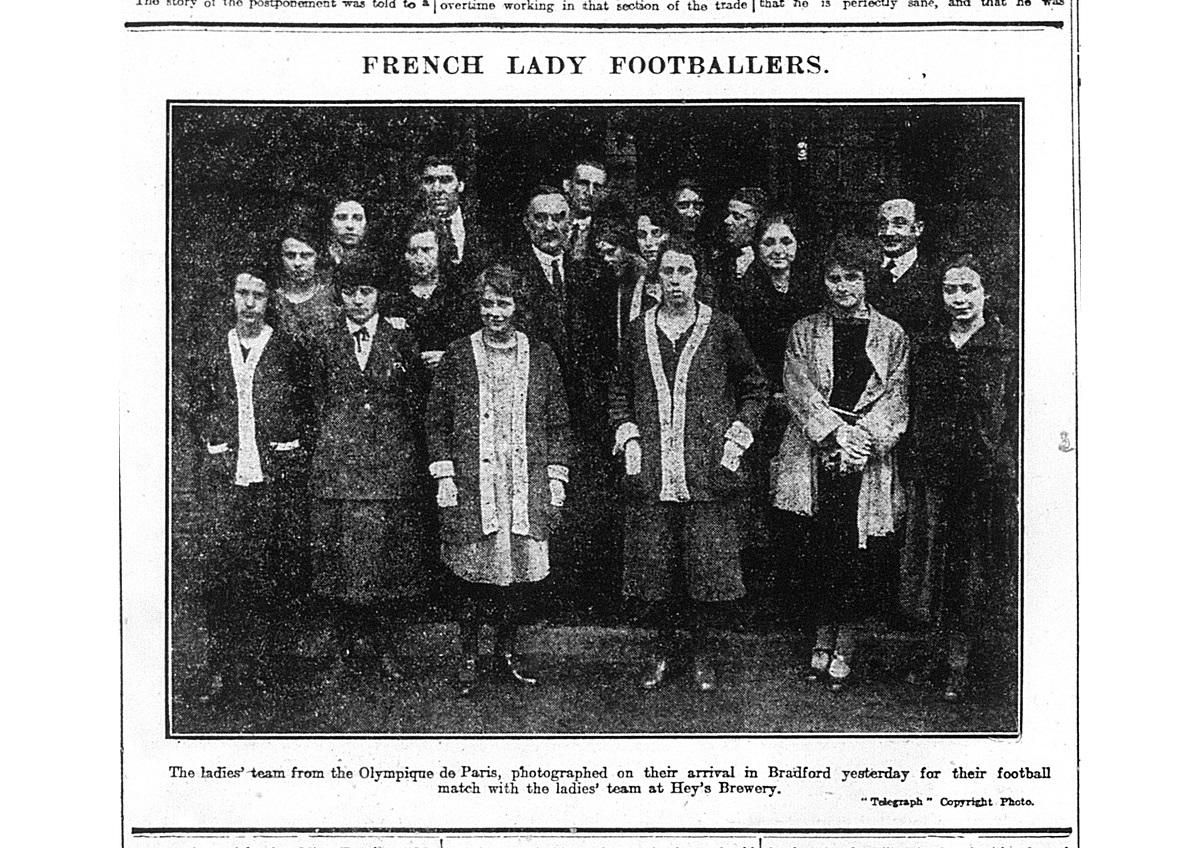

The match was moved to what was rapidly becoming Hey’s home ground, Greenfield at Dudley Hill. The French team, Olympique de Paris, contained five athletic champions in their ranks. Their arrival in Bradford caused great interest. They were photographed on the steps of their base, the Rawson Hotel (owned by Hey’s Brewery) before the match. The game was played in aid of Rheims Cathedral Restoration Fund, the cathedral was severely damaged by German shelling in the Great War, and the Bradford Hospital Fund.

On March 28, 1922 an estimated 3,000 spectators saw Hey’s defeat their French opponents 2-0. Among the match reports is a line that suggests that Hey’s may have been poaching players from other Yorkshire clubs as it was said that Lucy Bromage had ‘again’

turned out for Hey’s. Bromage usually played for Doncaster Ladies and was the daughter of the former Derby County and Leeds City goalkeeper Harry Bromage.

After the match at Greenfield Stadium, both teams were treated to tea at Bradford’s Victoria Hotel by the Bradford Hospital Fund Committee.

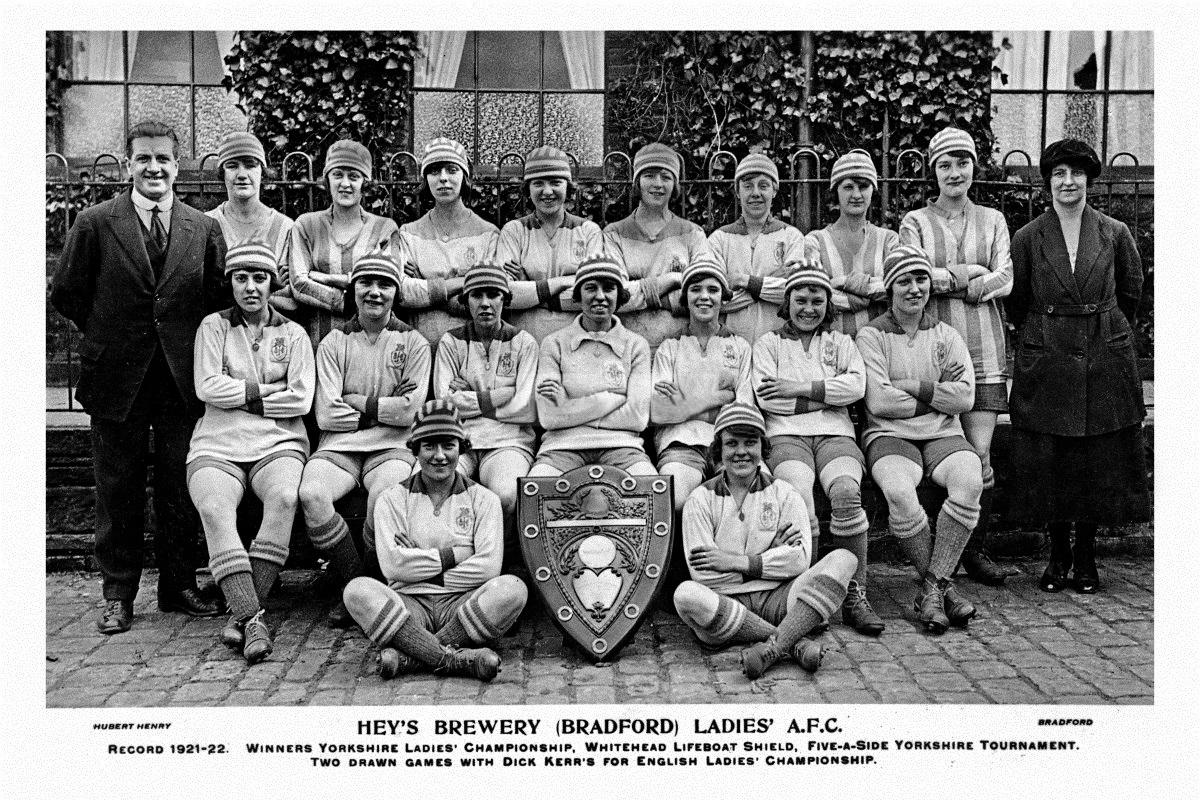

Domestically, the highpoint of Hey’s Ladies came in the six team Whitehead Lifeboat Shield competition. Played during May 1922 it featured: Doncaster Ladies, Hey’s Ladies, Huddersfield Alexandra, Huddersfield Atalanta, Huddersfield Ladies and Keighley. Hey’s defeated Huddersfield Alexandria 4-1 and Huddersfield Atalanta 4-0 en route to the final. Around 5,000 spectators 34

witnessed the final at Greenfield when Hey’s defeated Doncaster Ladies 4-0. The Lord Mayor of Bradford Thomas Blythe presented the shield to Mabel Benson, the victorious Hey’s captain.

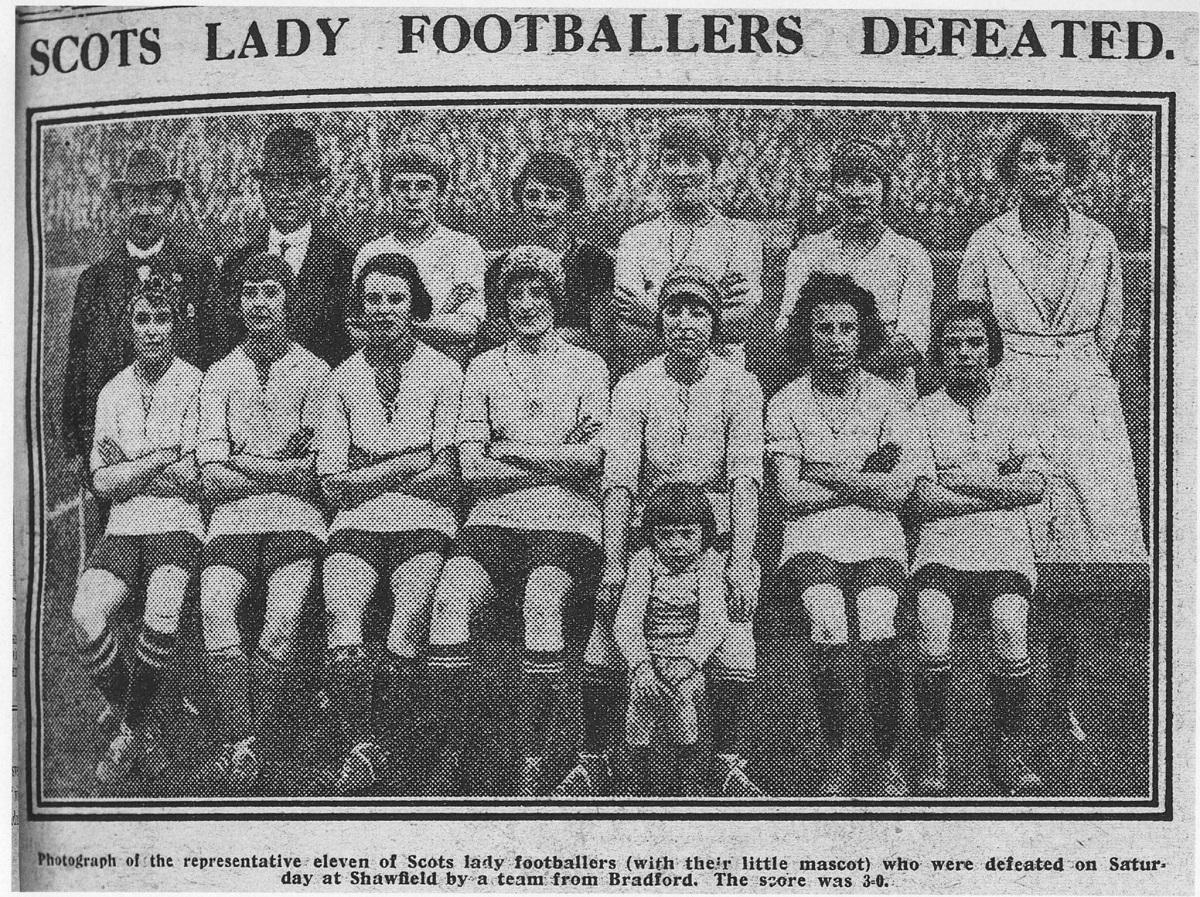

That victory saw the team invited to play games in Scotland, the south west of England and France. Although the match in Glasgow was against a team from Rutherglen, much of the press reported the game as a ladies international and referred to the two teams as Scotland and England.

Scotland, or Rutherglen, hit the crossbar in a goalless first half, but in the second period Hey’s dominated, scoring three goals without reply and brought a silver trophy back to Bradford. The trophy went on display in the King’s Head pub in Bradford, which was owned by Hey’s Brewery.

The following spring Hey’s were invited by the French Ministry of Sport to play, what was described as, the French Ladies international side. The match took place at the Stade Pershing in Paris on 29 April 1923. A crowd estimated at between 5,000 to 8,000 saw Jennie Harris score for Hey’s after 20 minutes, which was enough to win a tight match 1-0.

If any single event illustrated the dedication of the Hey’s Ladies to their sport it was their trip to Plymouth in May 1923.

After working all day on the Friday, the team caught the 21.00 train from Bradford and travelled overnight to Plymouth. They arrived in the West Country at 10.15am the following morning. After a further three hours travelling to Cambourne, they then walked over a mile to the ground where they defeated Plymouth Amateurs 5-1.

These high-profile trips in some respects obscured the fact that the FA ban was beginning to constrict the women’s game.

In contrast to other parts of the country, where women’s football ended abruptly, Leigh and Wigan being a case in point, Hey’s battled on. However, finding opponents became increasingly difficult and it is notable that Hey’s final games were against their old friends and adversaries Dick Kerr’s. In 1924 they played games against Dick Kerr’s in aid of causes as varied as Castleford Carnival funds and Burnley Cricket Club. The latter game was quite a spectacle, being floodlit, with electric lamps on 30 posts, and a white chrome ball was used.

By 1925 Hey’s Ladies switched sports and had taken up club cricket. It could be argued that disenchanted by the politics of football Hey’s turned their back on the game and took up cricket. Perhaps cricket offered an extension of the camaraderie that sport had offered them? Hey’s Ladies first reported cricket match was played against a team from the Bradford Dyer’s Association.

Hey’s Ladies scored 105 for the loss of four wickets. The Dyers’ Association side was all out for nine. ‘Tiny’ Emmerson (a winger from the football team), took seven wickets for seven runs. Margaret Whelan (scorer of several goals for Hey’s Ladies) captured three wickets for two runs. The team played in the Bradford Ladies’ Evening Cricket League. In 1931 they won all four cups offered in Bradford.

* This article was written in conjunction with Malcolm Toft, writer of articles for the Brewery History Society and Bradford CAMRA, and Michael Pendleton.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here