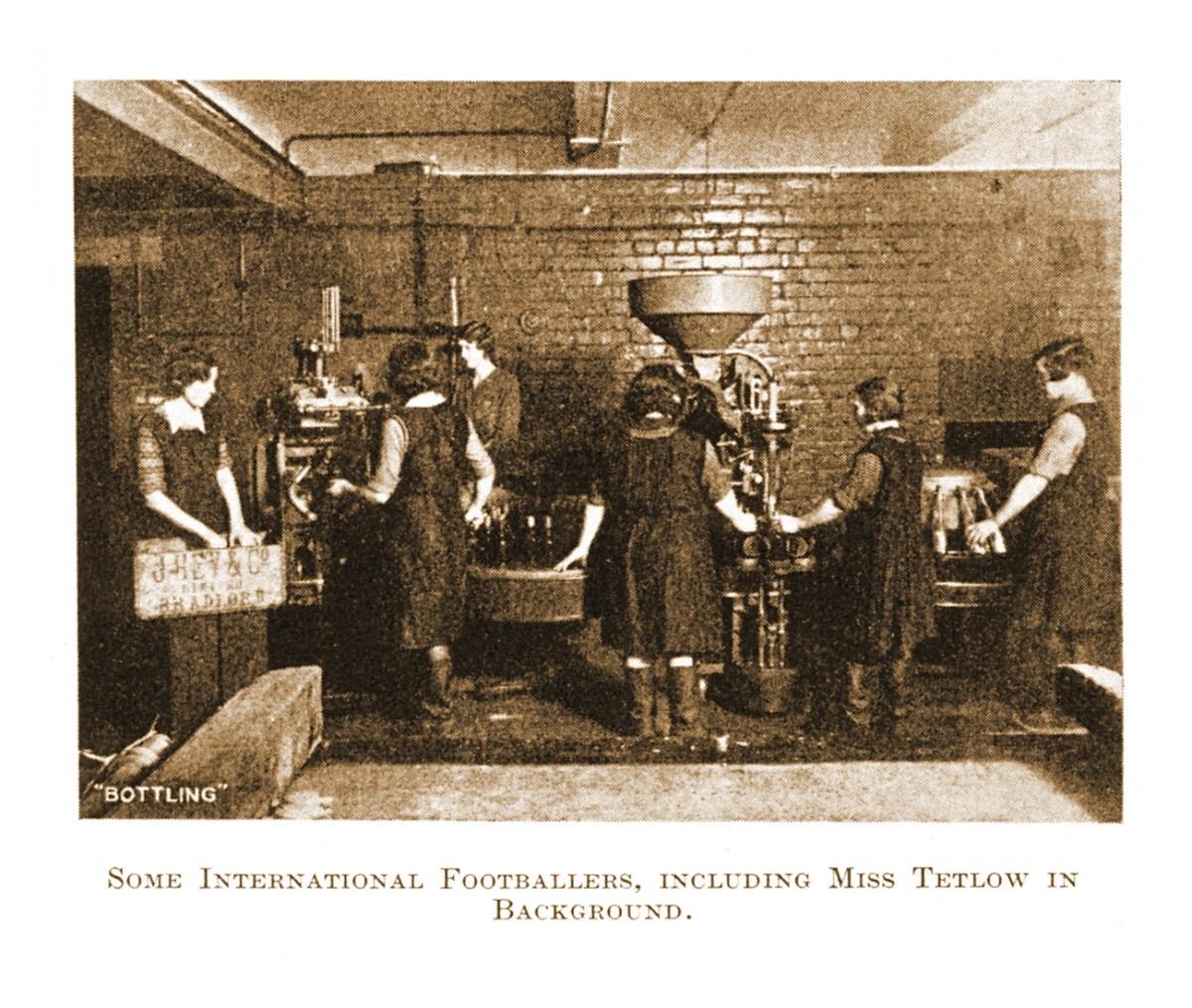

IT was from the bottling plant at Hey’s Brewery on Lumb Lane that Bradford’s finest women’s football team emerged.

This week saw the 100th anniversary of the FA ban on women playing at football league games. The game was “unsuitable for females,” declared the Football Association.

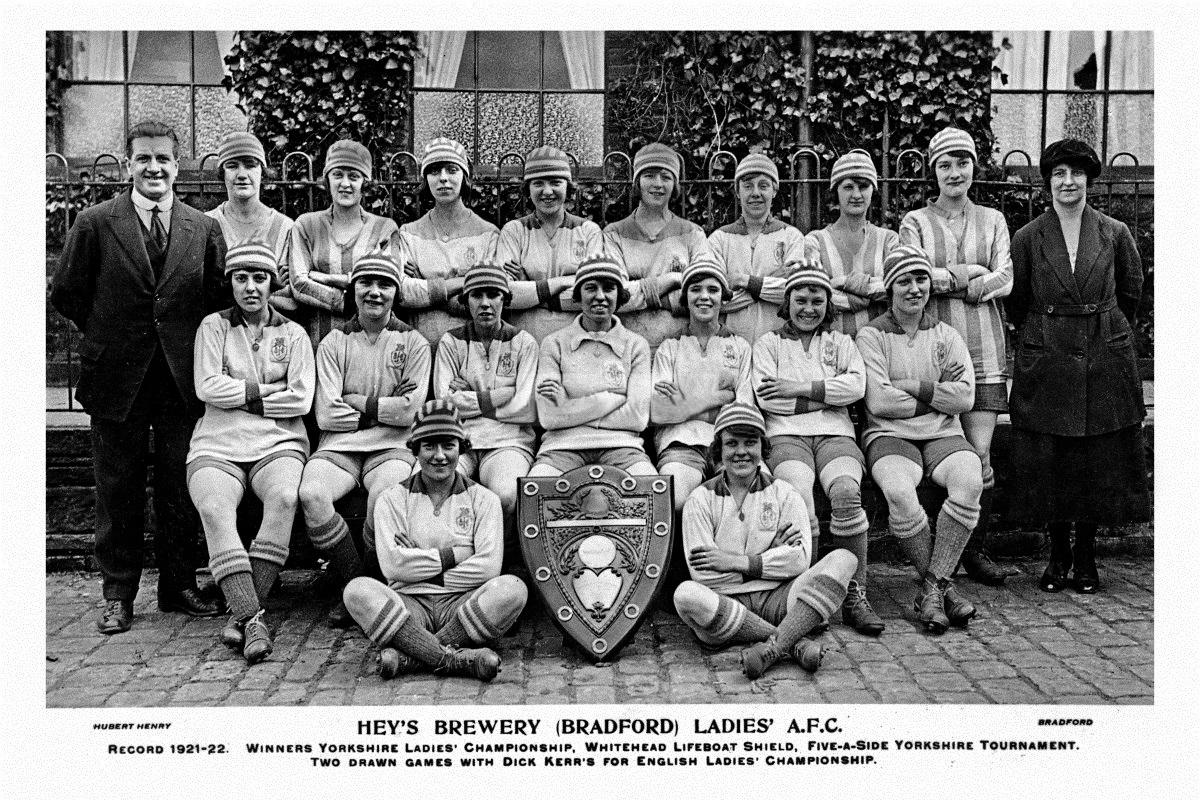

In the second of their series of articles, sports historian DAVID PENDLETON and KATHRYN HEY, a descendant of the brewery family, trace the rise of the famous Hey’s women’s team:

Hey’s Ladies’ first known game was against the Manningham Ladies at the Peel Park Carnival on May 18, 1921, with the Manningham team winning 5-1. The rematch was rather more successful for Hey’s, with the brewery side winning a five-a-side sports carnival 2-0 at Bradford Park Avenue on August 6, 1921. Around 8,000 spectators watched a men’s competition featuring sides from Barnsley, Bradford City, Bradford Park Avenue, Halifax Town, Harrogate, Huddersfield Town, Hull City and Leeds United. Although cultural factors noted earlier may have been a factor in the formation of another women’s team from Manningham, there may well have been an element of support from Bradford City AFC whose Valley Parade ground was a few minutes walk from Hey’s Brewery.

The links between the Hey family and Bradford City AFC are particularly compelling. Herbert Hey, a worsted manufacturer, directly related to the brewers, was a director of Bradford City AFC 1910-1913 and vice-president 1921-1922. Arthur Hey, general manager of the brewery, was also the chairman of Bradford City 1927-1929 and a director from 1933-1947. Judging by newspaper reports it appears that it was Arthur Hey who was the driving force behind Hey’s Ladies. That was not unusual as the majority of women’s teams in this era were headed by a male administrator. However, in the absence of company or football club records, it is impossible to establish whether Hey’s Ladies was formed due to Arthur Hey’s close associations with football, or whether it was the women themselves who initiated the team.

Of course, given the publicity afforded to the women’s game in the early 1920s, it is possible that the brewery was using the popularity of the women’s game as an advertising opportunity. But it’s unlikely to be the overriding motivation. What is certain is that women’s football fell on fertile grounds at Hey’s Brewery and it is without doubt that the Hey’s Ladies received enthusiastic backing from the company.

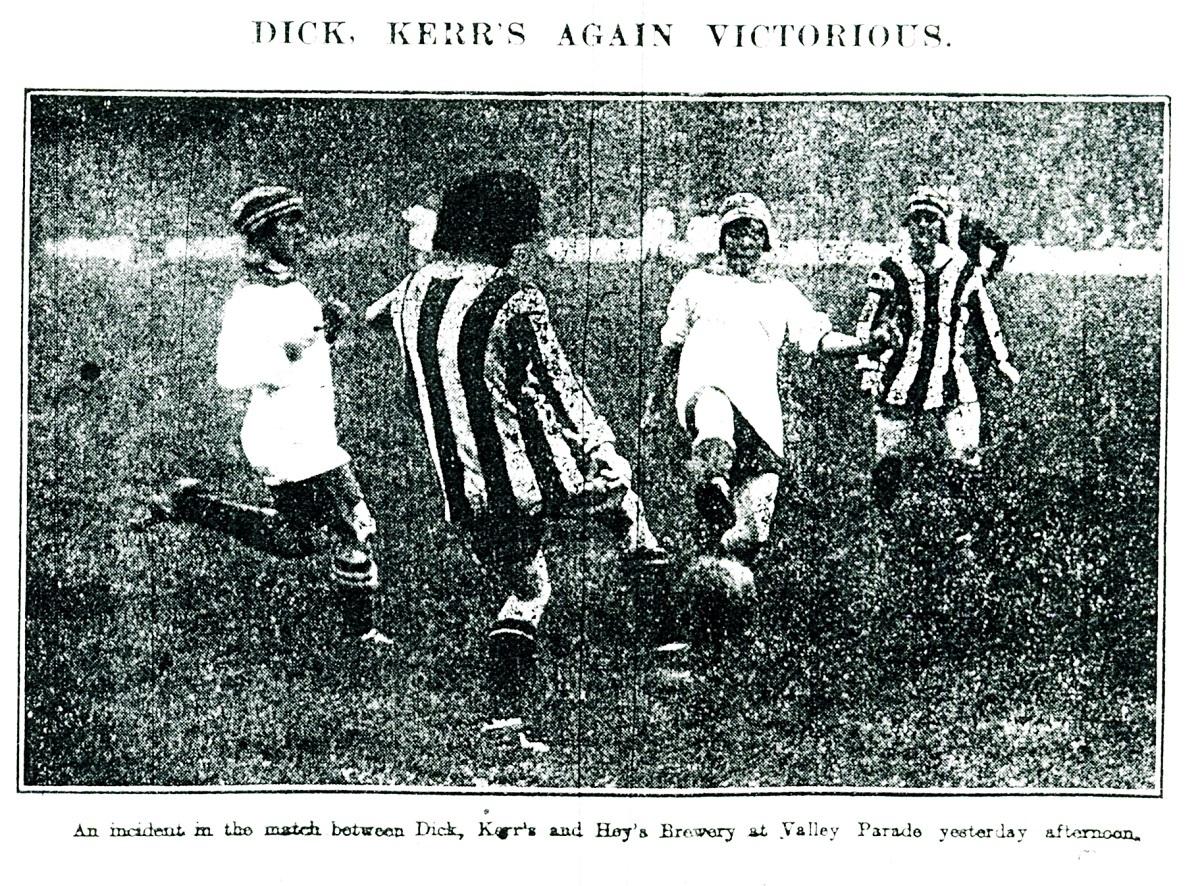

The close links between Hey’s Brewery and Bradford City AFC almost certainly led to Hey’s Ladies playing their first high-profile appearance at Valley Parade in a fundraising match in aid of the ‘New Motor Lifeboat Fund’. It was the beginning of a long association between the city of Bradford and the RNLI as the success of the fund led to a lifeboat being named ‘City of Bradford’, based at Spurn Head at the mouth of the River Humber. The fundraising match enjoyed civic patronage as the Lord Mayor of Bradford, Lieut-Col. Anthony Gadie, was credited with organising it. It took place on October 19, 1921. Inevitably, the famous Dick Kerr’s Ladies provided the opposition.

Acting as linesmen were Bradford City’s Scottish international keeper Jock Ewart and centre forward Frank O’Rourke. Hey’s Ladies lost 4-1, with Edith Jackson scoring the consolation goal. The attendance of 4,070 raised £184 for the New Lifeboat Fund.

The visits of Dick Kerr’s to Bradford was just a small part of the Preston-based team’s prodigious charitable and fundraising work. However, when women footballers played several matches to aid striking miners in Lancashire, it arguably gave the FA the excuse it was looking for to stifle the popularity of teams such as Dick Kerr’s. In December 1921 the FA banned women from playing on Football League grounds. Although the 24 intricacies of the ban will not be discussed in this article, it is worth reproducing the FA statement in order to illustrate the pressures being faced by the women’s game:

‘Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, the council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged. Complaints have also been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of receipts to other than charitable objects. The council are further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to charitable objects. For these reasons the council request clubs belonging to the association to refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.’

Arthur Hey informed the Press that, despite the ban, Hey’s Ladies ‘would continue so long as the girls wanted to play’. He defended

women’s football saying ‘the girls enjoy playing football, they work all the better for it and are much better in health’. Hey thought that it ‘was as if the FA were jealous of the girls encroaching on their sacred preserves’. He viewed the governing body’s actions as ‘interference practically amounting to impertinence’ and challenged the FA to divulge any evidence of alleged abuse of expenses. He stated that Hey’s Ladies only charged expenses if they undertook an ‘exceptionally long journey’. However, Hey did reveal that the players were paid ‘broken time’ if they suffered a loss in wages. The only fixed expense was insurance against injuries. This was in line with similar recompenses paid by Dick Kerr’s and may have been a standard model across the women’s game. He said the ladies team had cost the brewery £60 in subsidy since its formation eight months earlier.

On Boxing Day 1921 Hey’s were crowned ‘Champions of Yorkshire’ when they defeated the previously unbeaten Doncaster Ladies. Hey’s won by five clear goals and in subsequent publicity they were referred to as the ‘Yorkshire Champions’. Charity work continued to be at the forefront of Hey’s Ladies and on January 7, 1922 they met Dick Kerr’s to play a match in aid of the Wakefield Workpeople’s Hospital Fund. Due to the Football Association ban they were forced to play at Belle Vue, home of Wakefield Trinity Rugby League Club.

The use of a Rugby League ground is illustrative of the creative thinking women’s football was forced to adopt in order to find venues on which to play and circumvent the FA ban. Around 5,000 spectators saw, what was termed, a thrilling 1-1 draw. Florrie Redford opened the scoring for Dick Kerr’s after only 10 minutes with a strong cross shot. Mabel Benson in the Hey’s net, got a hand on the ball, but could not prevent the goal. Despite losing ‘Tiny’ Emmerson with a twisted knee after 55 minutes, Hey’s pressed hard for an equaliser. It came five minutes from time when the little centre forward, Edith Jackson, got through to score with a brilliant shot. However, Dick Kerr’s hung on to preserve their unbeaten record.

A rematch was arranged to take place at Greenfield Stadium, Bradford. The ground was a well-known athletics ground and had been the home of Bradford Northern Rugby League Club for one season in 1907/08. The match was to be played in aid of Manningham Soldiers Fund. Unfortunately, heavy snow caused its postponement, but the match eventually went ahead on February 18, 1922. Bradford East MP Captain Charles Loseby kicked off the game. The match was a high-scoring 4-4 draw.

Perhaps partly in recognition of the prowess of Hey’s Ladies, Bradford was becoming something of a centre for women’s football.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here