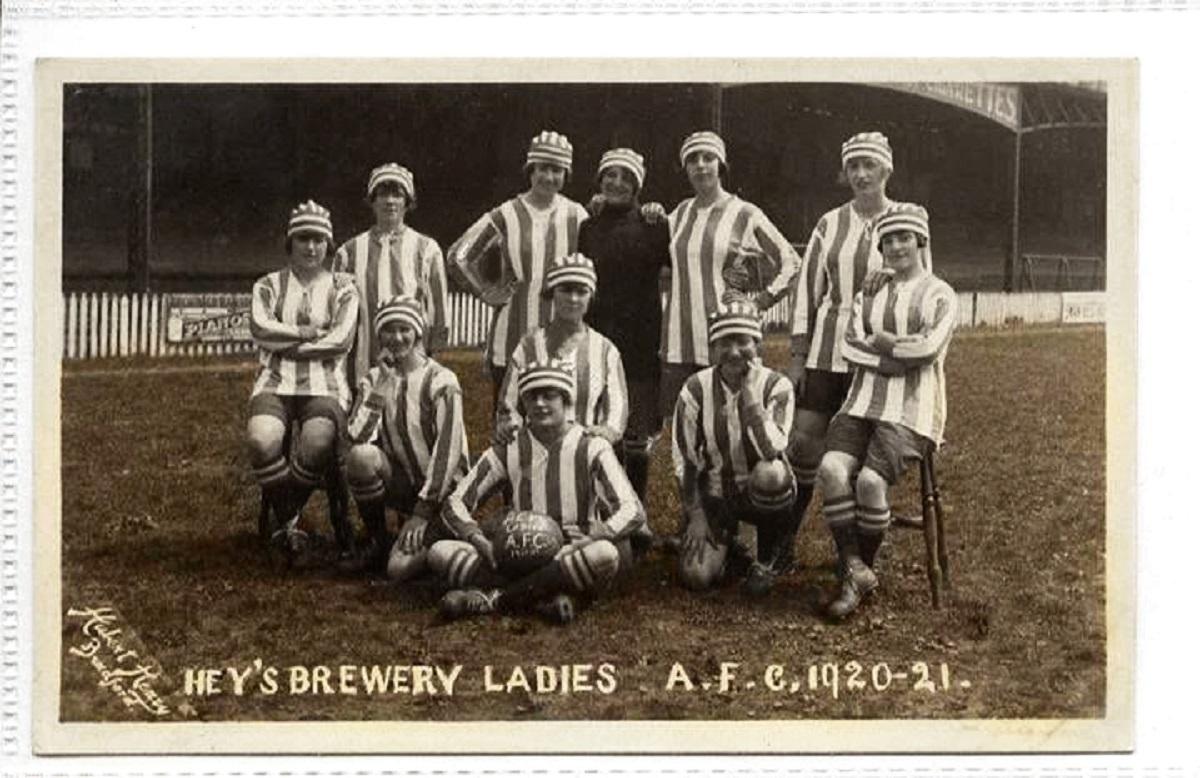

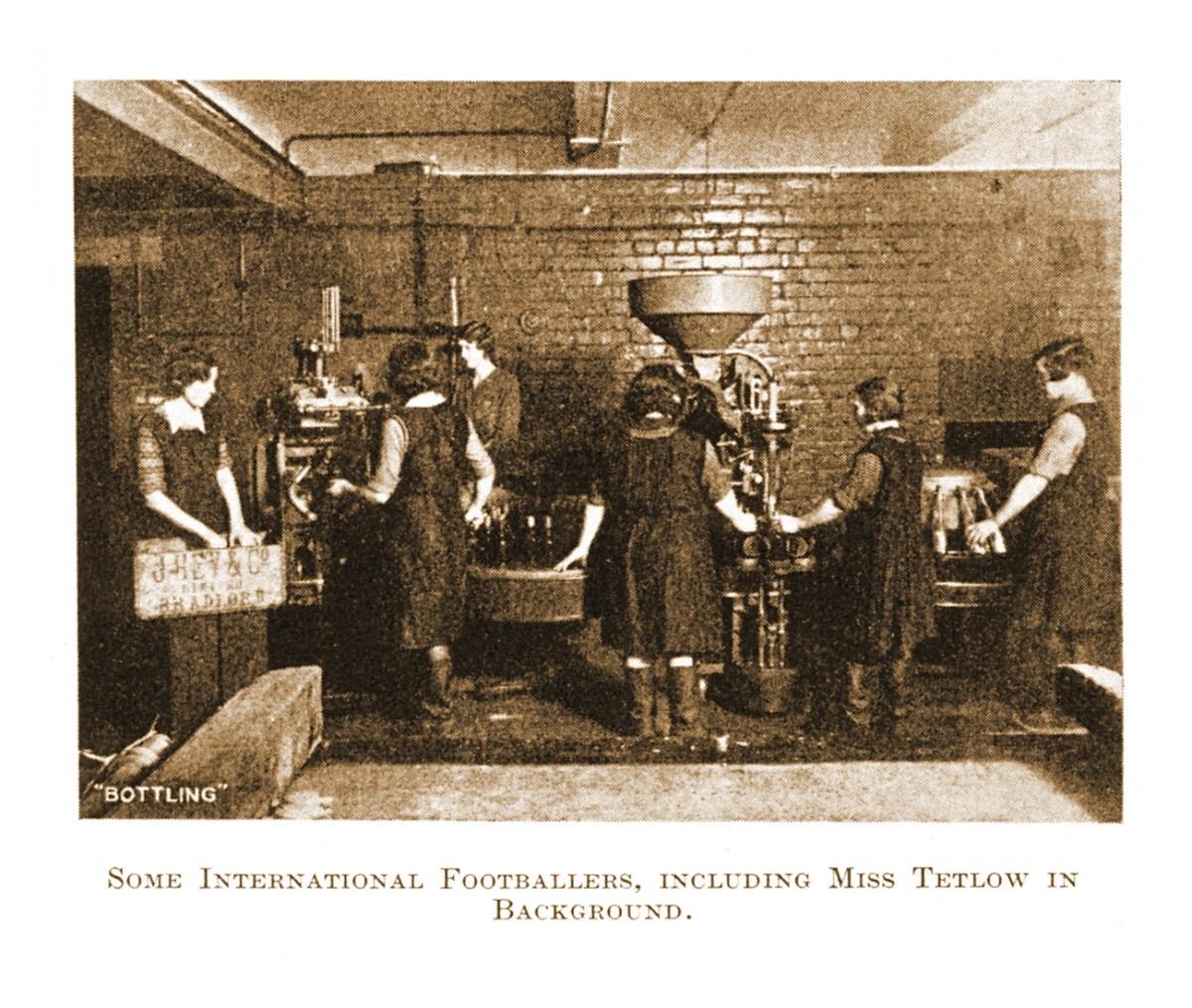

WITHIN two years Hey’s Ladies Football Club went from playing their first match at a park gala to representing England in France and Scotland. Conversely, two years later they had abandoned football in favour of club cricket.

A century on, women’s football is undergoing exponential growth as a participatory and spectator sport. The time is ripe to re-evaluate the achievements of young women from a Bradford brewery bottling plant who became one of the foremost women’s football teams of their generation.

The story of Hey’s Ladies is a snapshot of the tensions of gender, sport and the workplace that arose during the Great War. By retelling their story we give a timely reminder that expansion and popularity brought challenges in the 1920s that could be revisited, a century on, as the women’s game enjoys another era of growth. On Sunday it is 100 years since the FA banned women from playing at football league grounds.

This article has been written in conjunction with Malcolm Toft, writer of articles for the Brewery History Society and Bradford CAMRA, and Michael Pendleton.

Before delving into the story of Hey’s Ladies, it’s worth placing their achievements into a historical framework. Pinning down the first recorded game of women’s football is a moveable feast. Until recently, academics viewed a match at Inverness in 1888

as the first recorded game, whatever the truth of that, there’s no doubt that it was the First World War that transformed women’s football. With so many men fighting at the front it was women who stepped forward to fill gaps in the workplace; working in factories, driving trams, delivering post and much more. It is estimated that over one million women entered the workplace during the war. The cultural impact of the empowerment of women, who didn’t even have the right to vote, cannot be overstated, particularly given the context of the Suffragette campaign which had been suspended for the duration of the war.

The influx of women into hazardous industries, particularly munitions factories, raised official concerns. Government supervisors were sent to observe and make recommendations regarding their welfare. One recommendation was that sporting activities should be encouraged. Football was taken up with such zeal that it almost became the official sport of the so-called ‘munitionettes’. Although they were a highly visible element of women’s football, many other industries that employed large numbers of women also spawned football teams, supported in Bradford with teams from iron works, textile mills and a brewery.

From at least 1917 women’s football teams were active in Bradford. In September that year a match took place at Bradford Park Avenue featuring teams from Thwaites Bros. Ltd. iron works of Thornton Road, and Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Ltd. Bradford The matches were probably played in aid of injured servicemen and families of men killed in action. Inevitably some of the women playing would have had fathers, husbands, brothers or sons who had been killed or wounded, so participating in the games would have been deeply personal.

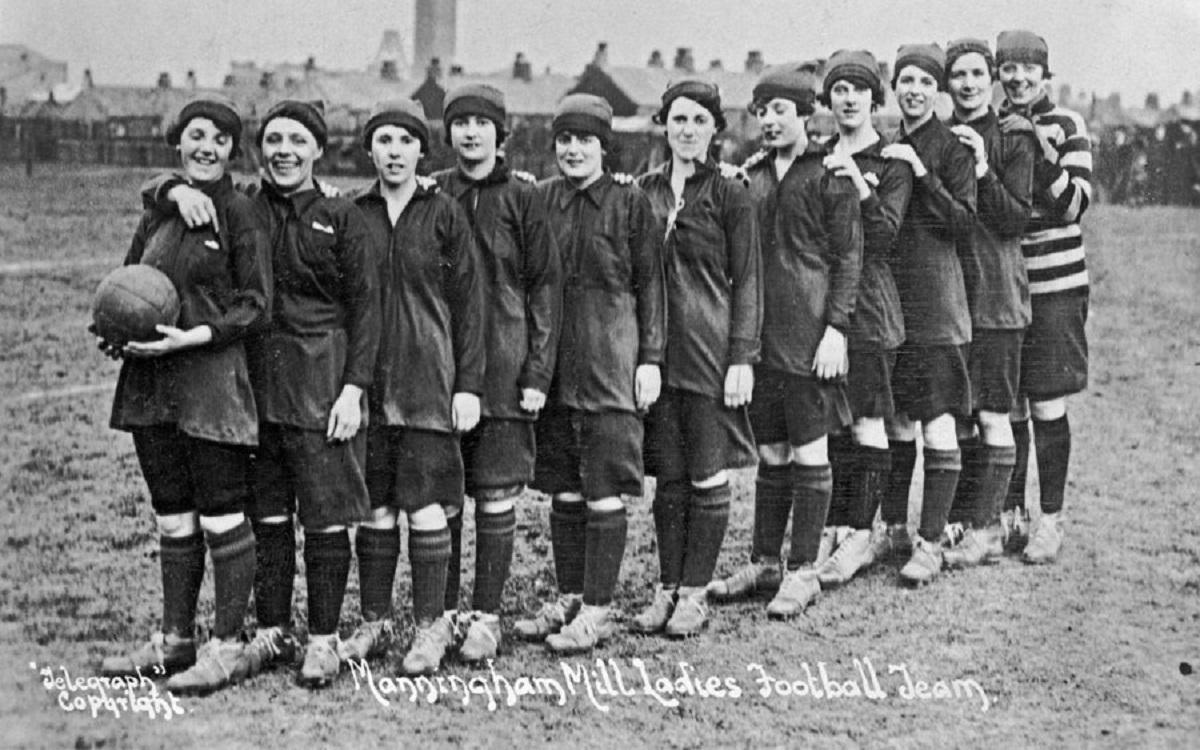

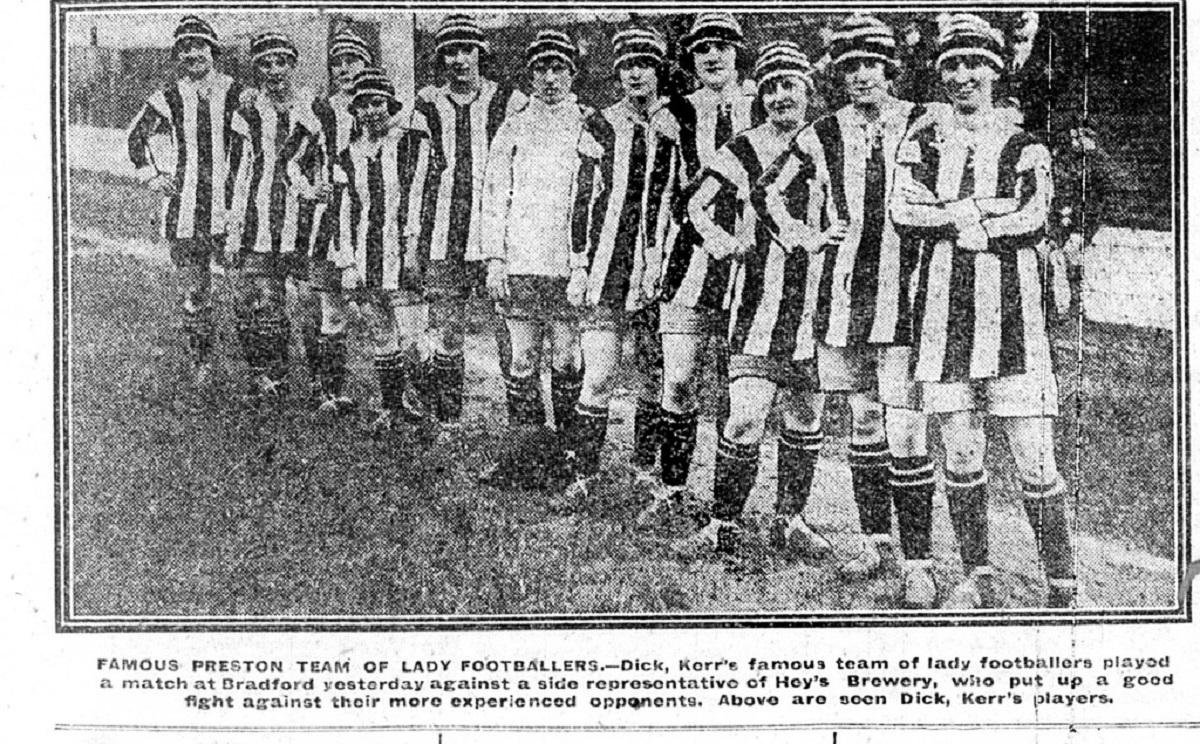

Undoubtedly, the most famous of the women’s works’ teams was the Preston-based Dick Kerr’s Ladies who popularised the women’s game after the war. By the 1920s they had become the de facto England women’s national team. By contrast most Bradford-based works teams appear to have disbanded after the war ended in 1918. However, one team, perhaps inspired by Dick Kerr’s, was formed in 1921 as Manningham (or Lister’s) Ladies. The bulk of the team was made up of Lister’s Mill hockey team. Both teams were part of a huge paternalistic sports section provided by the millowners and subscriptions deducted from the workers’ wages.

When it was announced that Manningham Ladies would meet the famous Dick Kerr’s Ladies at Valley Parade, there was considerable interest. A large crowd watched their final practice match on Manningham Mills’ Scotchman Road playing fields. Photographs appeared in the local press of the training and left-winger Holden was said to be ‘the Dickie Bond of the team’; Bond being Bradford City’s famous England international winger. Miss Derry captained both the Lister’s football and hockey teams. In a press interview she said she’d seen Bradford City play twice, but the majority of the players had never been to a match. However, Derry, and her team mate Bogg, had gained valuable experience when they played the previous week for a combined Yorkshire and Lancashire team that had met Dick Kerr’s at Leeds.

On April 13, 1921 Manningham Ladies played Dick Kerr’s Ladies at Valley Parade. Bradford City’s captain George Robinson acted as referee, while other City players Frank O’Rourke and Dickie Bond ran the lines. The involvement of those high-profile players can be viewed as overt support for women’s football, but it should be remembered that all three men would have been deeply affected by the Great War. Bond had served with the Bradford Pals at the Somme and had ended the war in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany.

Around 10,000 spectators saw Dick Kerr’s run out comfortable 6-0 winners, but the Manningham Ladies, despite being formed only six weeks earlier, were said to have given a good account of themselves. The £900 raised by the match was split between Bradford Hospitals and Earl Haigh’s Fund for former servicemen. After the game both teams dined at the Great Northern Victoria Hotel and later took in a show as guests of honour at the Alhambra.

It is worthy of note that Manningham Ladies were representing the enormous Manningham Mills complex. A generation earlier, in 1890-91, the mill was at the epicentre of the infamous Manningham Mills strike, involving a predominantly female workforce in a dispute over wage cuts. The strike collapsed after a riot, but ultimately led to the formation of the Independent Labour Party.

In the years leading up to the Great War, Manningham was at the forefront of the suffragette movement in Bradford. Drawing a direct line between those events and the prevalence of women’s football in the area may indicate that Manningham was more culturally receptive to the empowerment of women.

Manningham Mills was a short walk from Hey’s Brewery. It was from the latter’s bottling plant, and largely female workforce, that the Hey’s Ladies football team emerged. Given the proximity of the two workplaces, it is likely that the highly publicised exploits of the Manningham Ladies would have given inspiration to the formation of a team at Hey’s.

l See the T&A on Wednesday, December 8, for David and Kathryn’s next article, looking at the rise of Hey’s Ladies team.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here