THE factory system in the Industrial Revolution was not responsible for child labour. For centuries children had been employed in agriculture, looking after animals, sowing seeds, picking crops, and in the domestic system, helping their parents produce cloth.

They often worked a 12-hour day, but it was flexible, with breaks at parents’ discretion. This type of child labour was a necessity for family survival.

But with the growth of mills the nature of child labour began to change. Charles Dickens referred to the “dark satanic mills” and historian EP Thompson described them as places of “sexual license, foul language, cruelty, violent accidents, and alien manners.”

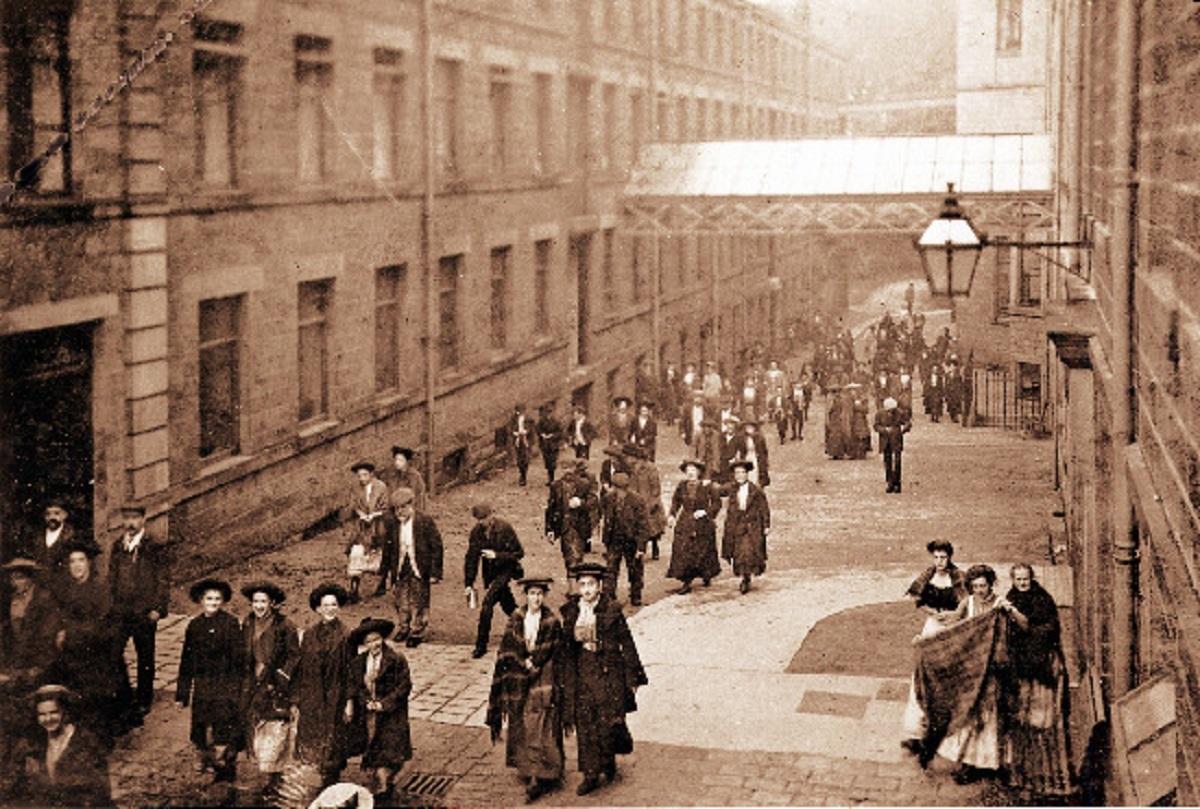

The factory system became notorious for strict discipline, harsh punishments, unhealthy working conditions and low wages.The children who suffered most were child apprentices from orphanages and workhouses. Often they had no wages, but were given lodgings, food, and clothing. In 1784 about a third of mill-workers were apprentices, and in some up to 90per cent were children.

At Greenholme Mills, Burley-in-Wharfedale, owners Greenwood and Whitaker in 1818 employed 147 children from London. This moved some to campaign for the abolition of child labour, but legislation such as the 1802 Factory Act was ineffective.

Samuel Collier and Harriet Norman both had fathers lost at sea and were placed in an orphanage. They were sent to Washburndale, Samuel was 10 and Harriet, nine, and worked in the Washburn Valley near West End village, later flooded to make way for Thrushcross Reservoir.

Registers for the parish of Fewston list children who died at an early age in mills. Samuel and Harriet married in Fewston in 1823 and moved to Keighley where their son Robert was born. They moved to Blubberhouses and when he was eight Robert was sent to work in the mill. He worked there for six years, one of his legs became twisted and bowed. Many other boys suffered the same affliction. At the end of the day he was so tired he could barely drag his body home. He worked 13 hours a day, five days, and 11 hours on Saturdays, for two shillings a week. At 5.30am the factory bell would sound and children had to be up to walk to the mill to start work at 6am. Many worked on spinning machines until midday. They weren’t allowed to sit, and if caught resting they were lashed by the overseer with a leather strap. They stopped work at 8pm, exhausted and crippled in their arms, backs and legs.

For Robert and other young children, there was some relief under the 1833 Factory Act, when children between nine and 13 weren’t allowed to work more than 48 hours a week. His working hours were reduced from 76 to 48 hours. Aged 14 he became an apprentice blacksmith to John Birch, Ilkley, escaping the grim experience of factory work.

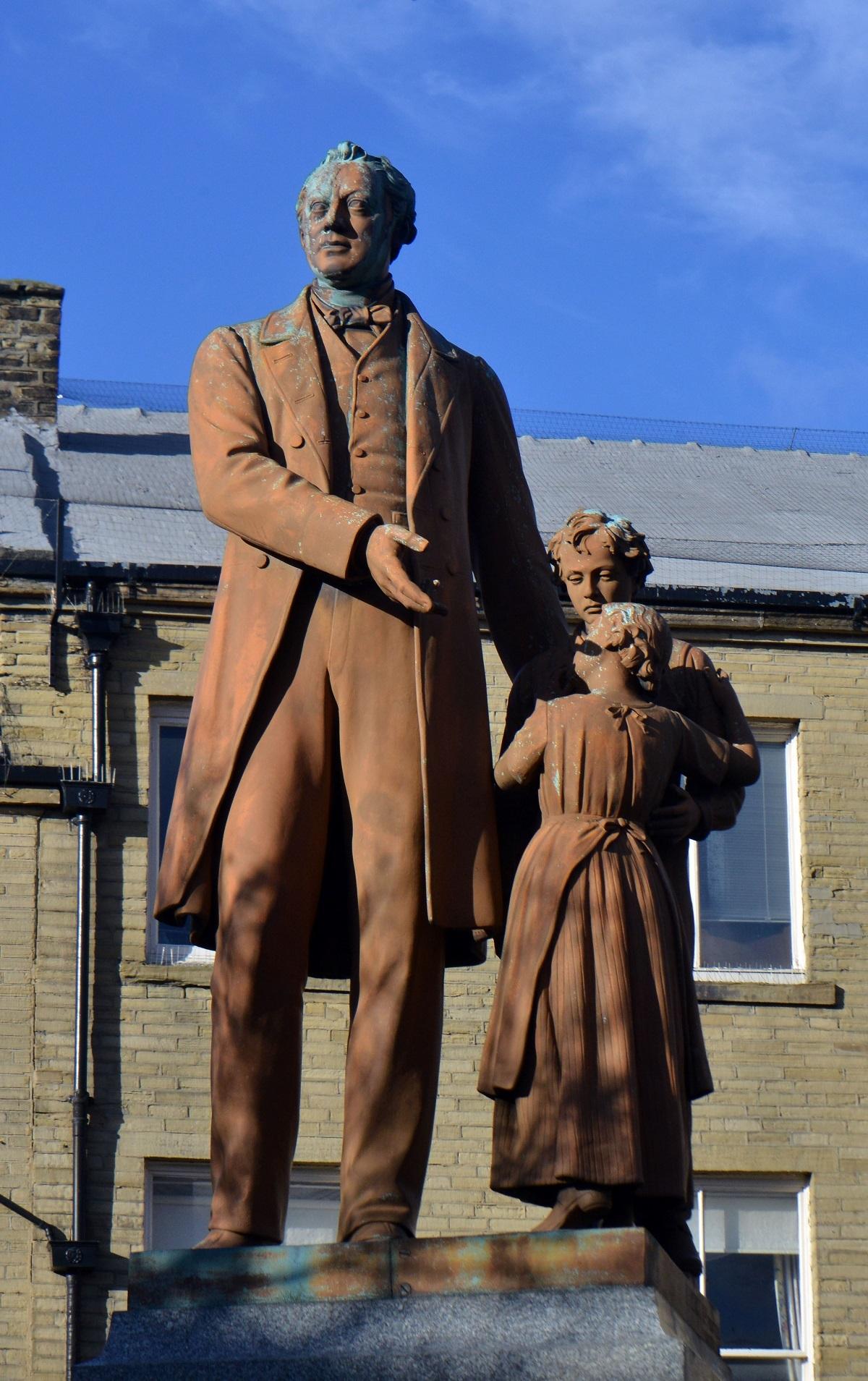

In the square behind North Parade, Bradford, is a statue of Richard Oastler who campaigned for the abolition of child labour. He was born on December 20, 1789, the son of a clothing merchant. After meeting John Wood, a Bradford worsted manufacturer, in 1830, he joined him in the campaign to abolish child labour. Even though Wood was a more humane mill-owner, children still worked 12-hour days. Oastler was a Tory who opposed trade unions, but he believed it was the responsibility of the ruling classes to protect the weak and vulnerable. He opposed the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act because he thought it too harsh. His view was to protect children by legislation.

He wrote to the Leeds Mercury attacking the employment of children. He said child labour was as bad as slavery and gave evidence to a committee investigating the employment of children. The evidence from this (1831-3) shocked those who read it. Children were questioned and described conditions they worked in. Doctors, overlookers, magistrates, and parents were also interrogated: “When she was a child, too little to put on her own clothes, the overlooker used to beat her till she screamed.’

‘Gets many a good beating and swearing. The overseer carries a strap.’

‘The boys are often severly strapped; the girls sometimes get a clout. The mothers often complain of this. Has seen the boys have black and blue marks after strapping.’

‘Has often seen workers beat cruelly. Has seen girls strapped; but the boys were beat so that they fell to the floor in the course of the beating, with a rope with four tails, called a cat. Has seen the boys black and blue, crying for mercy.’

Elizabeth Bentley gave evidence aged 23 and said she began work in Mr Busk’s flax mill as a little doffer aged six. She worked 5am-9p.m, her job was to stop the frames when they were full, take full bobbins to the roller, then put empty ones on and set the frames again. If they flagged they were strapped. If parents complained they lost their job. Dust got onto her lungs and pulling baskets dislocated her bones.

Gillett Sharpe was Assistant Overlooker of the Poor in Keighley. He had three children working in the mill; the eldest daughter became crooked in her limbs, the boy was weak in his knees and could scarcely walk. Sharpe couldn’t afford to take them out of the mill.

Joseph Habergam from Huddersfield had weakness in his knees and ankles and could hardly walk. His brother and sister would take him under each arm and run with him about a mile to the mill. If they were late the overlooker beat them. Their mother was a widow and relied on their wages, but it made her cry to see them deformed.

Jonathan Down worked at Marshall’s mill from age seven. He told the inquiry that if a child was drowsy the overlooker would take them to a corner where there was an iron cistern filled with water. He took them by the legs and ducked them in headfirst, then sent them back to work wet through.

Samuel Coulson was a tailor in Stanningley with three daughters in a mill. One was bruised across the shoulders by the overlooker’s strap, but pleaded with him not to complain because she’d lose her job.

Alexander Dean spoke of an orphan girl who worked with him and was given food and clothes but no wage. One day she was tangled up in machinery and her clothes were ripped off her back. When they pulled her out she was scolded for neglect.

According to Bradford doctor Thomas Beaumont, working long hours with nutritional deficiences brought severe deformity to factory children. Fortunately some enlightened Bradford mill-owners, like Wood, and campaigners like Oastler succeeded in petitioning Parliament to stop child labour, reduce the hours of adults, and improve working conditions.

The investigation resulted in the 1833 Factory Act, making illegal to employ anyone under nine. Children aged nine-13 must not work more than nine hours a day, and must have two hours of schooling.

l See Saturday’s T&A for the next part of Dave Welbourne’s article looking at how mills were inspected and how conditions improved for child workers.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel