ON March 23, 1895, at Crouch End in London, a women’s football match took place between the North and the South of England. It was organised by Nettie Honeyball who became the first secretary of the English Ladies Football Team.

The North beat the South, 7-1, in front of a crowd of 10,000. It was an historic occasion which inspired the rise of women’s football. Yet the Guardian, reporting on the match, concentrated on what the women were wearing. The reporter concluded that once the novelty had worn off “I do not think ladies football matches will attract crowds, but there seems no reason why the game should not be annexed by women for their own use as a new form of recreation.”

In the late 19th century there was an emphasis on fitness to combat the appalling effects of poverty and associated diseases. This could be seen after 1870 in the Board Schools, and ‘Muscular Christianity’ movement within public schools. There was some interest in ladies football in public schools. In 1894, Brighton High School for Girls had an enthusiastic team, but interest declined after complaints from parents, and the Head’s insistence that the ball could only be kicked if it was on the ground. The headmistress of Rodean thought hockey and tennis were more suitable, with perhaps cricket, which she thought beneficial for physical development and character building. Furthermore, college principals objected to ‘nice’ girls playing against working-class factory workers, nurses and shop workers.

It is unclear when women’s football originated, but there is some evidence from a fresco in China that women were playing during the Dong Han Dynasty (25-220 AD). Women were probably participating in the lawless Medieval version of football between opposing villages. In 18th century Scotland, there was a ritual whereby a team of married women took on single women to display would-be brides to a predominantly male crowd. But it was Nettie Honeyball who pioneered women’s football. Games were organised in the North and Midlands in 1895. In Scotland it was expanding due to Lady Florence Dixie.

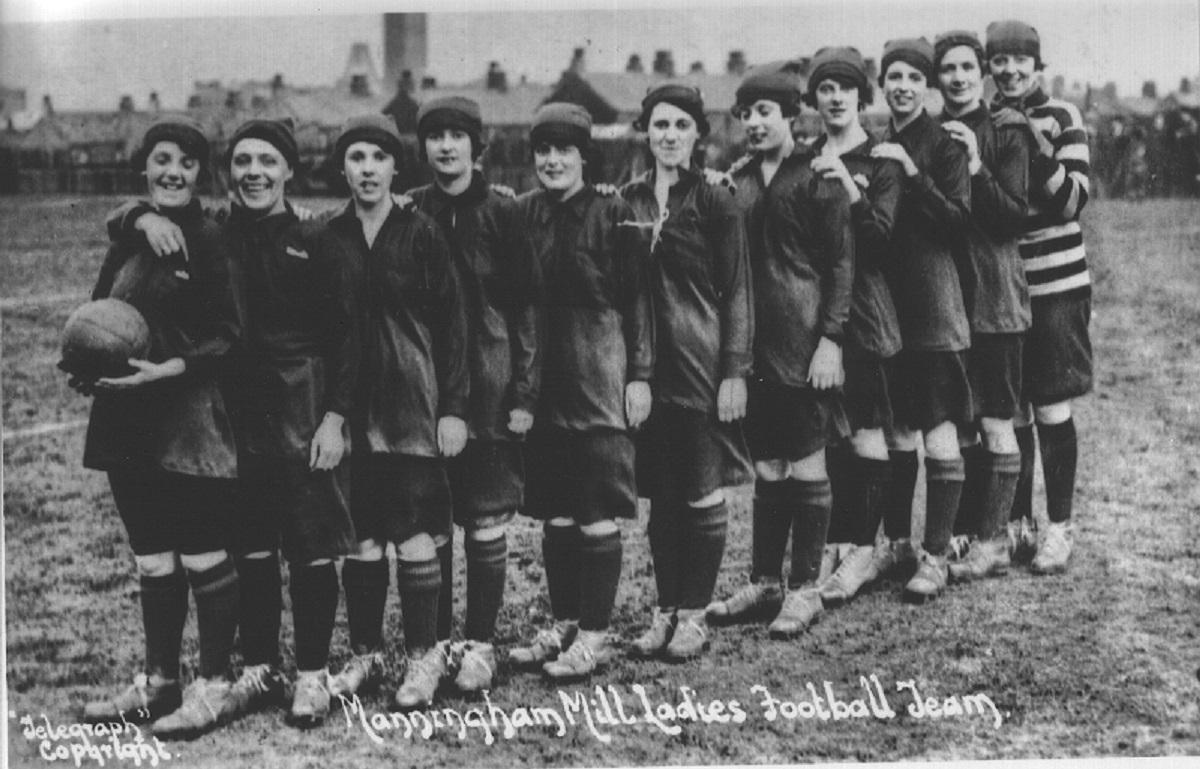

In Bradford in 1895 there was a short-lived women’s team four years before the Bradford and District Football Association was formed, and eight years before the birth of Bradford City. But interest was waning by the turn of the century and in 1902 the Council of the Football Association instructed members not to play matches against ladies teams. It was the First World War which brought

about a revival and acceleration in the number of teams and games.

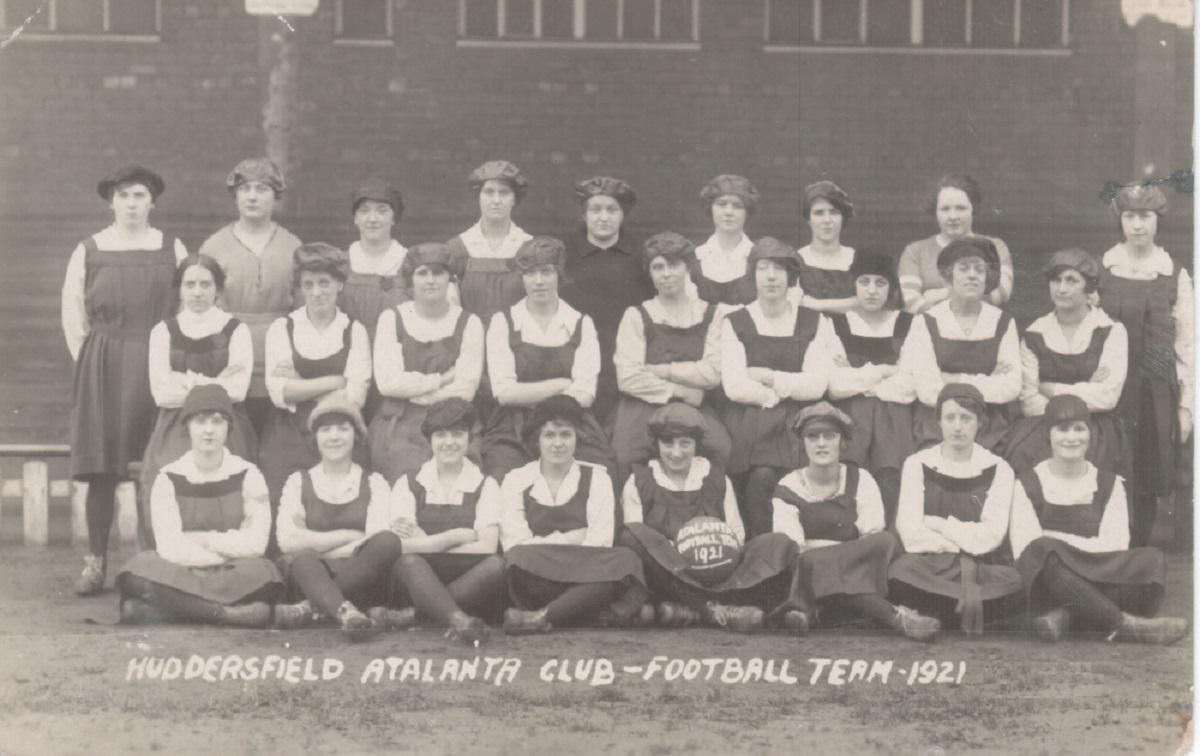

As more men went to war, gaps were filled in industry and agriculture by women. Many also worked in dangerous munition factories. Their war efforts led to women over 30 winning the vote in 1918. During the war they gained a new independence and bonding in the factory was translated into team games. Across the country, especially in the North, groups of women began to organise football teams. Players came from various backgrounds. Ada Beaumont, who played for Huddersfield Ladies’ sports club Atalanta, was concerned that the club might be full of higher class women. But these fears soon subsided, leading her to comment that it was factory workers who dominated because they were used to ‘the hard knocks of life’. Factories encouraged women’s teams, providing pitches and facilities, believing it would keep them fit and increase morale at work.

The team that shone in this period was Dick, Kerr’s of Preston, an engineering works that switched to munitions. Like other women’s teams, they raised a great deal of money for charity. Between 1917-1923, £70,000 went to ex-servicemen, hospitals and poor children. Charity matches drew large crowds, so the Football Association allowed women’s games to be played on League grounds. In the North-East, the Blyth Spartans Munitionettes were formed in 1917. The women worked at Blyth’s South Docks, loading ships with ammunition, and were taught to play football by sailors on the beaches. Star of the team was coal miner’s daughter Bella Raey, who scored 133 goals in a season. They won the Munitionettes Cup in 1918, beating Bolckow-Vaughan at Ayresome Park. Bella scored a hat-trick. At St James Park, Newcastle, on July 6, 1918 a team of Tyneside Internationals played the North of England in 1-1 draw. One player, Mary Lyons, was a 14-year old from Jarrow who represented England against Northern Ireland on September 21. Nicknamed ‘the Dynamo’, she scored two goals in the 5-2 victory and still holds the record for being the youngest, male or female, to play for England.

A letter from ‘Munitioneer’ in the Blyth News, August 30, 1917, began: “I have heard more than once some very uncharitable criticisms of the young women playing these matches...asserting that it is not decent for them to appear in public in ‘knickers’. May I say that these girls are doing an excellent work of charity in playing. Some are a bit boisterous, but they have hearts as big as lions. There is no doubt of our winning the war while we have such women (heroines I call them) as mothers of the race.”

After the War, Dick, Kerr’s Ladies invited a French team to England. The team, which arrived in April 1920 to raise money for British soldiers and their families, included shop assistants, shorthand typists, nurses, factory workers, dress-makers and book-keepers. They were received by enthusiastic crowds at matches in Preston, Stockport, Manchester and Chelsea.The first two games were won by Dick, Kerr’s, the third drawn, and the final game at Stamford Bridge a victory for the French team, who admitted they’d learnt a great deal about playing football and good sportsmanship from the English players.

The Preston ladies had a profound influence on women’s football at home and abroad. Dick, Kerr’s played in France in front of thousands in 1920, making a positive contribution to Anglo-French relations. On April 6, 1921, they beat a Yorkshire and Lancashire XI, 7-0, at Leeds United’s ground, raising £1,700 for the Railway Benevolent Association. Days later they beat Lister’s Ladies 6-0 in Bradford before a crowd of 15,000 and raised £1,555 for unemployed ex-servicemen.

The standard of women’s football was rising but, as my next article reveals, women footballers were not always taken seriously and were sometimes treated as curiosities.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here