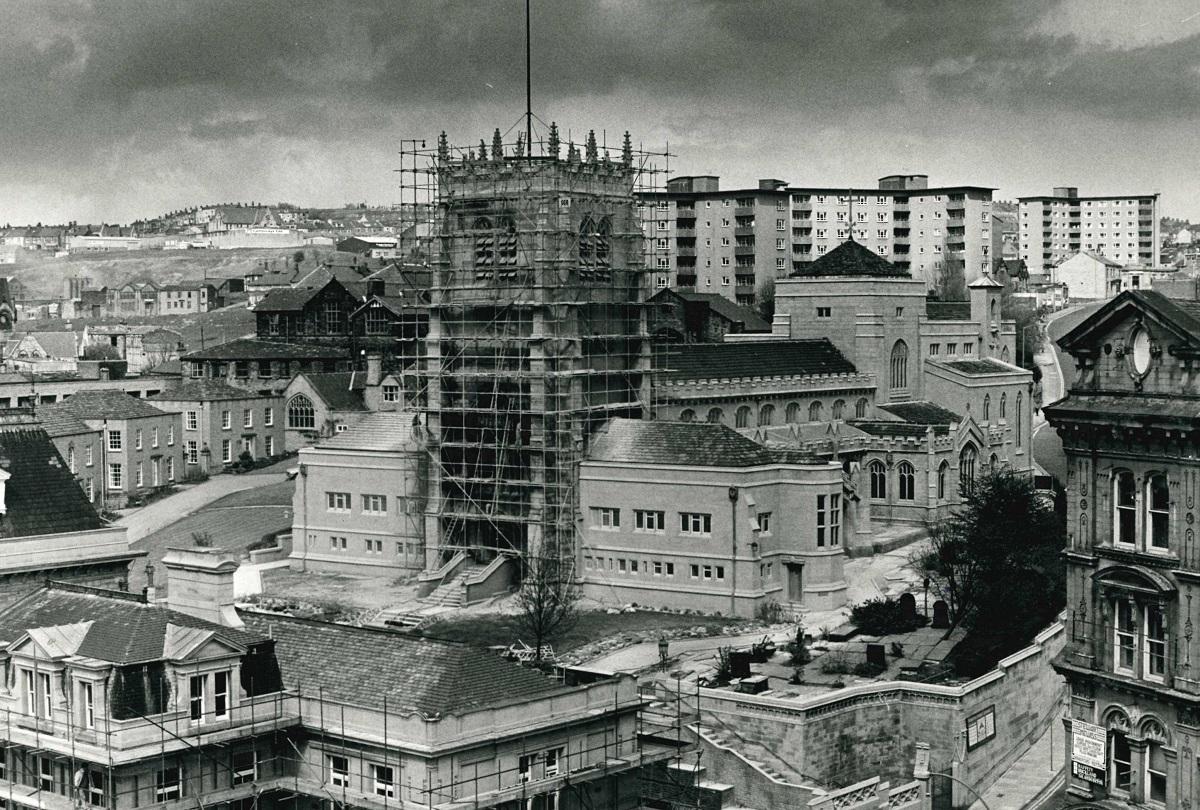

‘DON’T look down!’ he said sharply, as I clung nervously to the narrow iron staircase on the whitewashed wall on the inside of City Hall’s 200-feet-high Florentine tower.

Gingerly, I edged my way to the top up a ladder with a sheer drop - to be rewarded for my courage by a magnificent view of the city. This was in the chilly November of 1983 and I was in the company of Clock Superintendent Bob Watmough, a fascinating and informative man who had just completed 30 years’ service with the council.

Back then it was a very different city. In the ensuing article in the T&A, on November 19, 1983, I wrote: ‘Bradford is revealed as a city of domes: prominent are those three threatened ones of the Alhambra; the two green ones of the Odeon; and those of Britannia House, the Yorkshire Bank and Rawson Hotel.’ Fortunately my fears for the survival of the theatre were unfounded.

From the four vantage points of the windy parapet, 180 feet high, it was easy to appreciate the beauty of the city’s bowl shape. It seemed to offer a never-ending succession of views of itself, compact, busy, grey - silver under the low sunlight - merging with half tones and receding to peripheral greens. From here were teasing glimpses of distant hills.

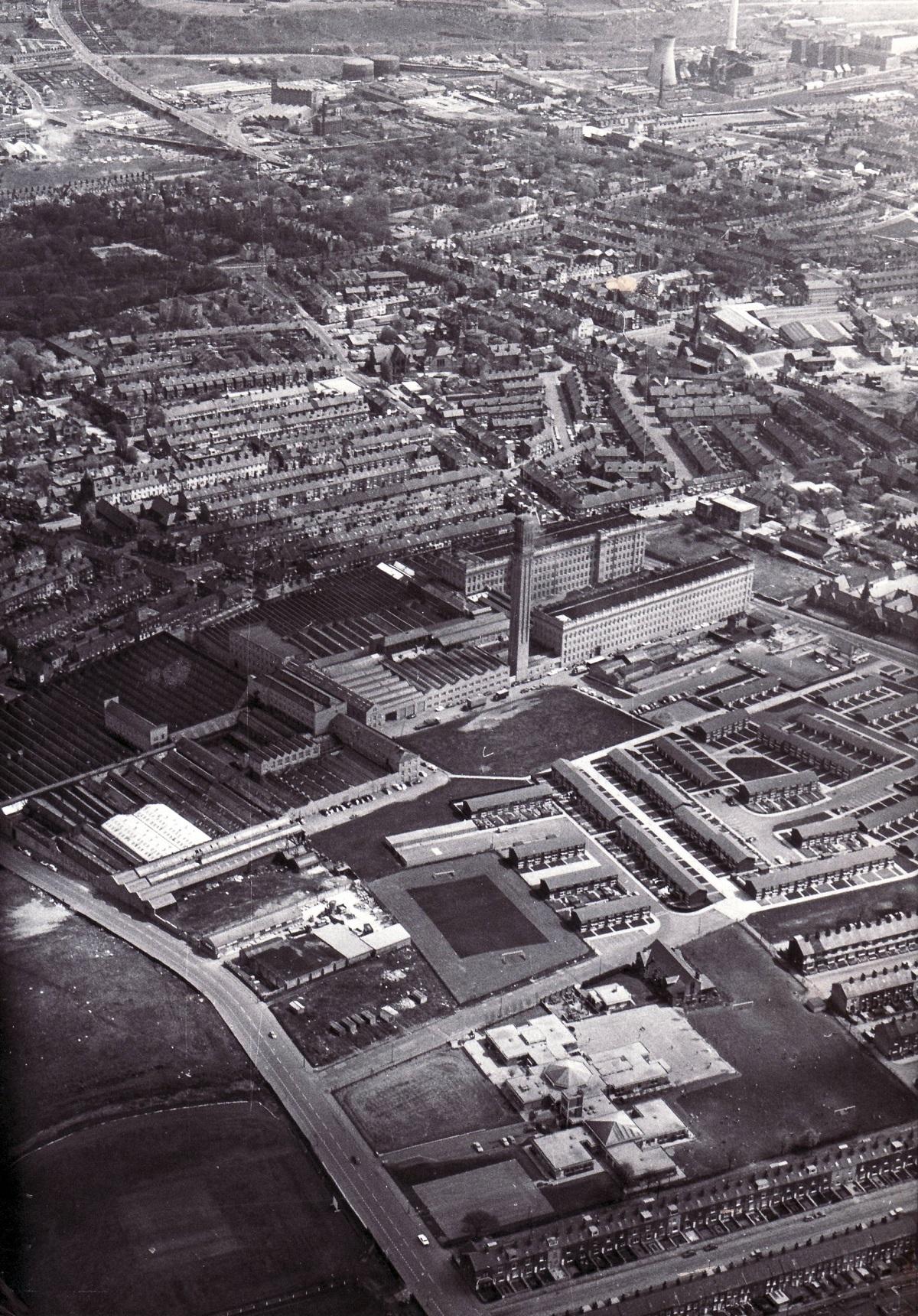

It is, of course, height that gives the noblest views. There is a dizzying prospect from Baildon Green’s Walker Wood, Saltaire in the foreground the colour of river sand, the mill a magnificent Italianate stronghold I never tire of beholding.

From Carr Lane winding up the Crags to Wrose, the sweep from a splintery urban skyline to a green swathe stretching to Keighley still takes my breath away. I used to take evening walks up here in the later 1960s with my Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and witnessed quite frequently the depressing tell-tale sight of smoke billowing from another redundant mill somewhere across the city that had somehow set itself on fire.

Speaking of long views, I know of few better than that from a walk around Beacon Hill, Wibsey, one of so many places in Bradford steeped in history. Here was once one of the many beacons forming a chain throughout the country in readiness to give warning of invasion - or, happily, to celebrate some momentous achievement. This eminence, almost 1,000ft above sea level, yields an unbroken curve from the trees of Bowling Park to the undulating heights of Queensbury. Flats high-rising in Manchester Road point a prominent line down which the eye runs to where modern structures crowd the familiar central tower. The roof of Bradford City’s Midland Road stand, Geoffrey Richmond’s legacy, still seems to give off a glow of the exciting footballing times in which it was built. The city is there at your feet.

Time was when much of Bradford from a distance appeared dark and dingy but the modern city wears only the lightest haze, making views even in deepest winter the more spectacular. A distant cluster of reddish roofs in the region of Bolton Woods catches the sun, and the eye sweeps to Wrose and blue-grey farthest Aireborough. Rombald’s Moor has a brownish-purple tint, rolling, solitary, mile upon mile.

Though straining for the horizon beyond the rectilineal street patterns of Girlington, the eye inevitably fixes on an immense chimney, the 250ft monument of Lister’s, still the central landmark of most prospects of Bradford and once the largest silk factory in the world. It was here in the winter of 1890-91 the workers came out in one of the first and longest strikes of its kind. It is no coincidence that the Independent Labour Party, forerunner of the modern-day Labour Party, was formed in Bradford not long after, at a TUC Conference in January 1893. The great Keir Hardie was elected as its first chairman. The current leader of the party, Sir Keir Starmer, is named after him.

Heaton is marked by that stubby church spire of St Barnabas, an endearingly quirky sight since 1863. An expanse of olive-green must be Chellow Dene’s leafy purlieus. Allerton has flats and housing estates in open spaces where once was not much save Aldersley Farm. The brown roofs and red clearly divide old and new Thornton. And round by old Yews Green way neatly marked out are open fields, an assortment of dark green and browns. Queensbury and the Denholme Road are five gentle curves with today a pencil-textured hint of rain. I find the distant and local prospects to be had when ambling around up here, venturing into the lovely Shibden Valley, via Ambler Thornton, to Queensbury, to be incredibly beautiful. From the well-named Mountain, standing almost 1,200ft above sea level, the views are stupendous, stretching on a clear day to the smoking towers of Drax Power Station.

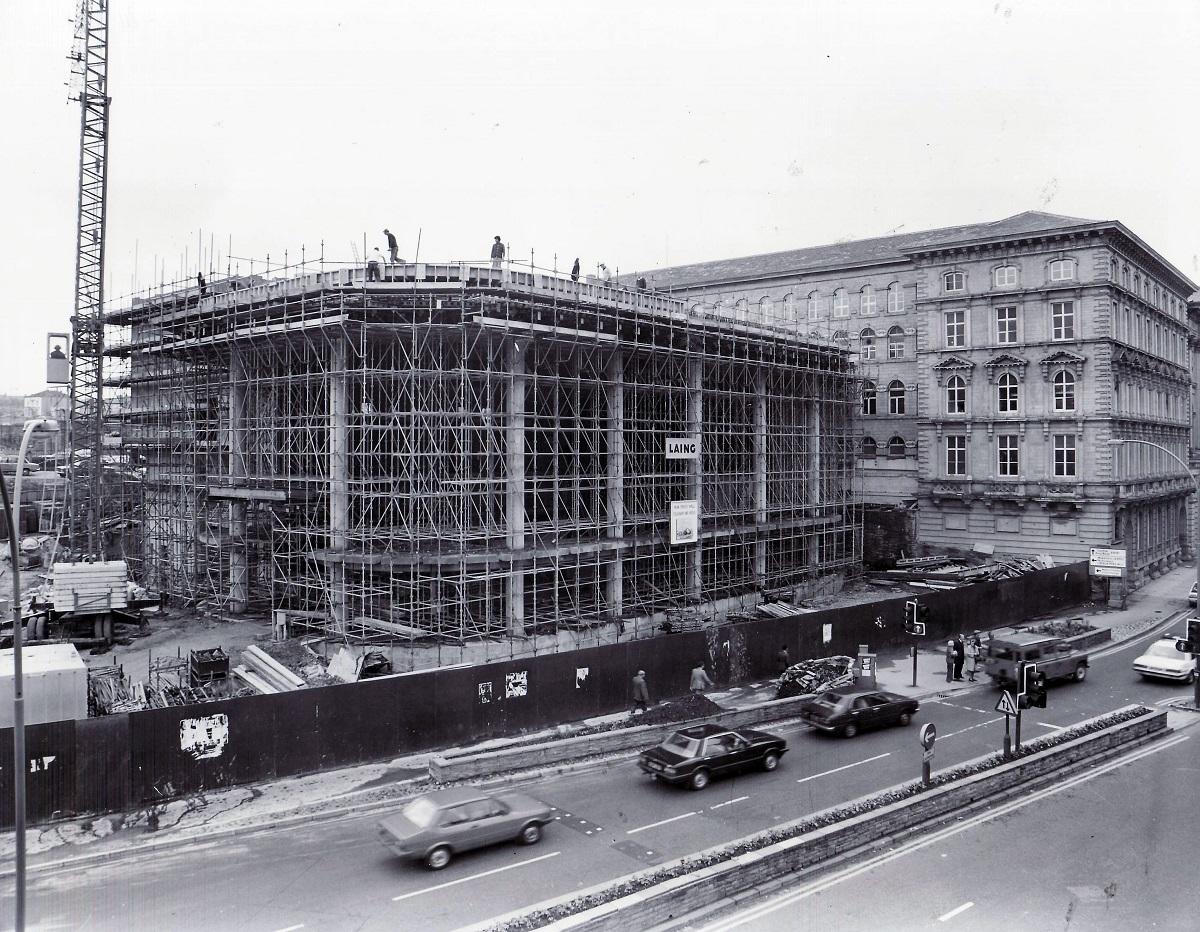

One of my ambitions post-Covid is to make a nostalgic return to City Hall, where I once worked in the Treasury Pay Office, climb the tower while I’m still able, gaze down at people enjoying themselves in City Park and compare the modern city with how I remember it. It’s here very clearly I remember hearing the clock mechanism ceaselessly clicking and clacking away - a striking metaphor for the passage of time! I don’t want to leave it too long.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel