BRADFORD’S Alhambra theatre will finally re-open on Tuesday, after closing in March 2020 due to the pandemic.

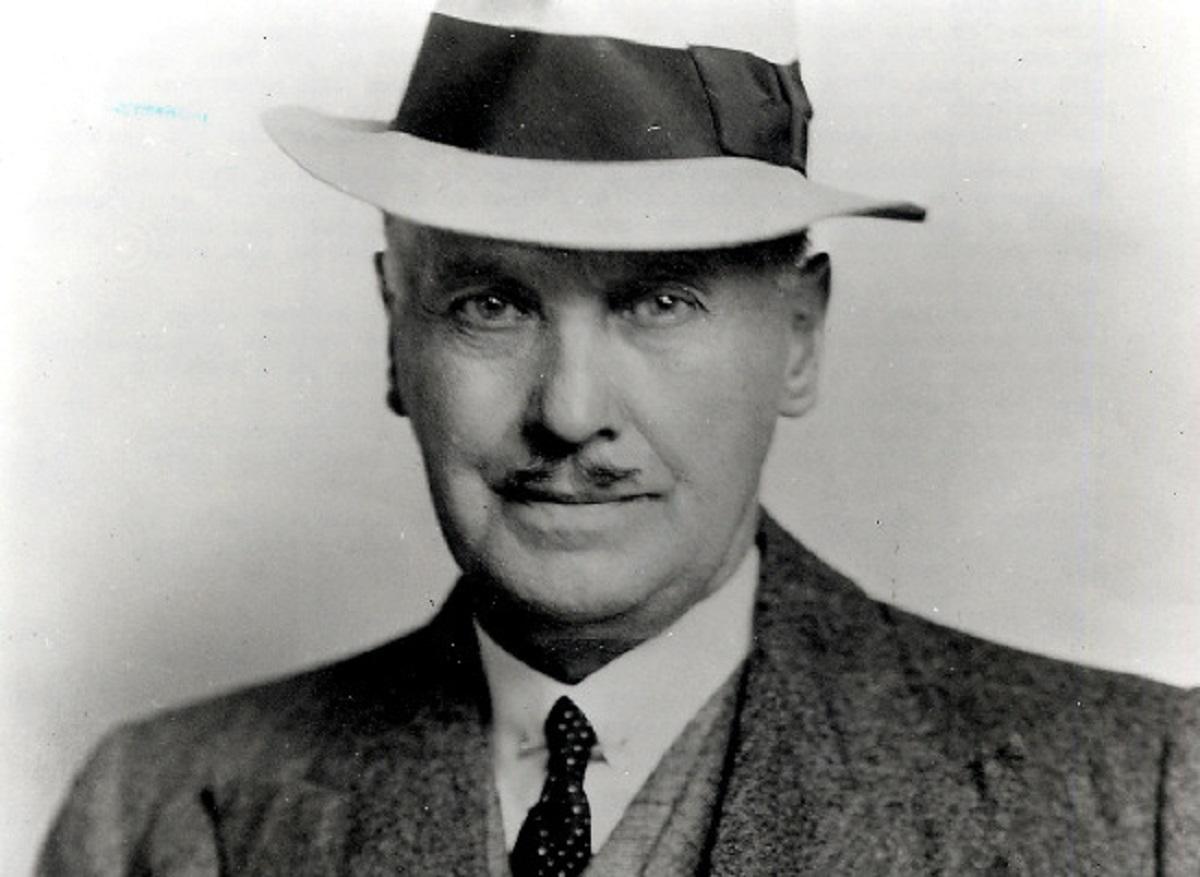

MARTIN GREENWOOD, whose book Every Day Bradford offers a story of the district’s people, places and events for each day of the year, pays tribute to the Alhambra founder who left a special theatrical legacy for the city, impresario Francis Laidler:

When Laidler took over joint management of the Prince’s Theatre on Little Horton Lane, he was the 35-year-old secretary of the Bradford Brewery Company. Laidler went into partnership with Walter Piper, the theatre’s general manager. While Piper concentrated on productions, Laidler was responsible for financial affairs in a part-time role, keeping his main job at the brewery.

Laidler had no previous experience of theatre. Born and bred in Teesside, he was apprenticed to the National Provincial Bank and moved to Bradford shortly after his marriage, aged 21, to become a wool clerk before moving to the brewery.

Under Piper and Laidler, the theatre had instant success with a pantomime, Red Riding Hood. It made a big impression, not just on the audience but Laidler who soon had to face a big decision. Within six months, Piper died. Should Laidler take the gamble of becoming the new proprietor and leave his secure job? He decided in favour of the theatre. If the success with the panto could be repeated, he’d make enough money to offset losses of other shows in the year. This was to become his guiding principle for the next 50 years of theatre management.

He was, however, not content to rest on his laurels. Another big decision was to present itself 10 years later, in 1912, when he eyed up an empty piece of land across the road for the site of a much grander theatre - the Bradford Alhambra.

Laidler faced competition from the Empire Music Hall (Great Horton Road), Palace Theatre (Manchester Road), Theatre Royal (Manningham Lane), and his own Prince’s Theatre, not to mention the growing number of cinemas offering entertainment. But he’d spotted the opportunity for a new theatre offering a more comfortable night out in relative luxury, with velvet seats and plush carpets. The name was deliberately exotic, after the Alhambra Palace in Granada, also the Moorish style design with a distinctive dome supported by Corinthian pillars, illuminated at night. It could seat 1,800 spectators, including four private boxes and tip-up seats. All seats could be reserved in advance - an innovation for the time. Situated in a commanding position in the heart of the city, it became the premier place for entertainment.

For the rest of his life Laidler lived for the Alhambra, although he owned others (The Prince’s Theatre, Leeds Theatre Royal and Keighley Hippodrome) and produced pantos in other cities. He even lived nearby, not in his home but in a suite at the Victoria Hotel, convenient for frequent rail trips down south.

In the last 40 years of his life almost every famous variety artiste of the era trod the Alhambra boards - including Billy Cotton, Norman Evans, Gracie Fields, George Formby (father and son), Grock the clown, Tommy Handley, Henry Hall and his band, an ageing Laurel and Hardy, Ivor Novello, a young Ernie Wise.

Laidler’s main legacy, however, was the tradition of the pantomime. He quickly realised that the key to longterm commercial success lay in successful pantos. His record as a producer was phenomenal. He managed over 250 productions across the country. No producer before or since has matched the record. His national reputation as the King of Pantomime was fully earned.

He put on 52 productions in Bradford, including Cinderella, Aladdin, Mother Goose and Robinson Crusoe. He was 35 for his first production and 87 for his last one. The first 29 were at the Prince’s Theatre then transferred to the Alhambra across the road for the next 23 - he owned both venues! His second wife Gwladys took over after his death in January 1955.

What made Laidler’s pantos particularly special were the Sunbeams; dancing troupes of young girls, auditioned locally, who often joined in the comic routines. Started in 1917, they were an immediate success, bringing a ray of sunshine to the dark war years.

The Sunbeams had to be at least 12-years-old, no taller than 4ft 3in, in good health and attend school regularly. He provided accommodation for some in a house managed by a house-mother. He also provided a uniform and money paid into each girl’s bank book, handed over to parents at the end of the season.

On October 13, 1956, one impresario, Val Parnell, unveiled a memorial plaque for another in the Alhambra foyer: ‘A tribute to the King of Pantomime, Francis Laidler, a philanthropist who loved to make children happy.’

* Every Day Bradford is available from online stores, including Amazon, and bookshops including Waterstones and Salts Mill.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here