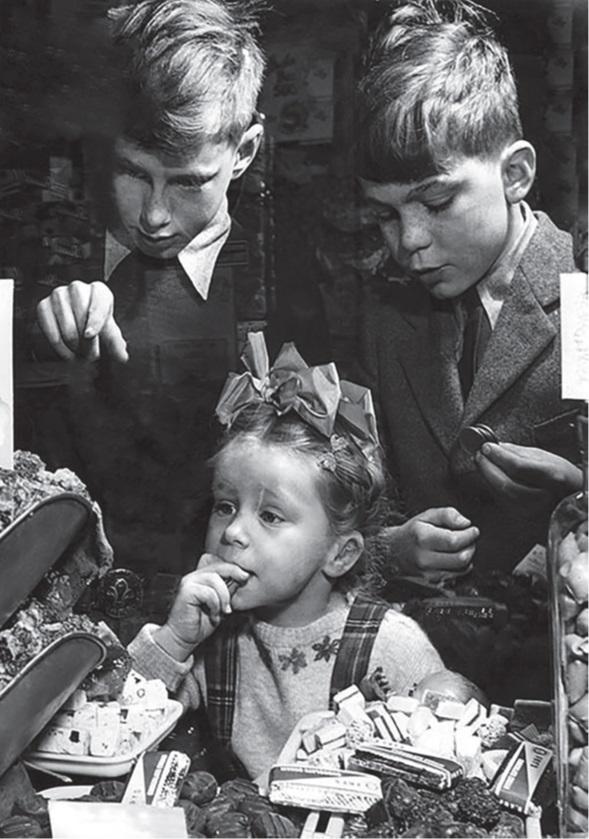

WHEN you pop to the shop to buy a bag of sweets, the last thing you would expect is to die from eating them.

Yet that is exactly what happened to 20 people who bought humbugs sold from a market stall in Bradford back in 1858.

As well as the 20 men, women and children who perished, more than 200 became seriously ill after taking home what they thought was a bag of tasty humbugs.

The sweets had been inadvertently made using arsenic. In fact, they contained enough arsenic to kill two people per humbug.

The 1958 case became known as the Bradford Humbug Poisoning and was talked about across the country. It is one of a number of such cases described in The History of Sweets by Yorkshire author Paul Chrystal.

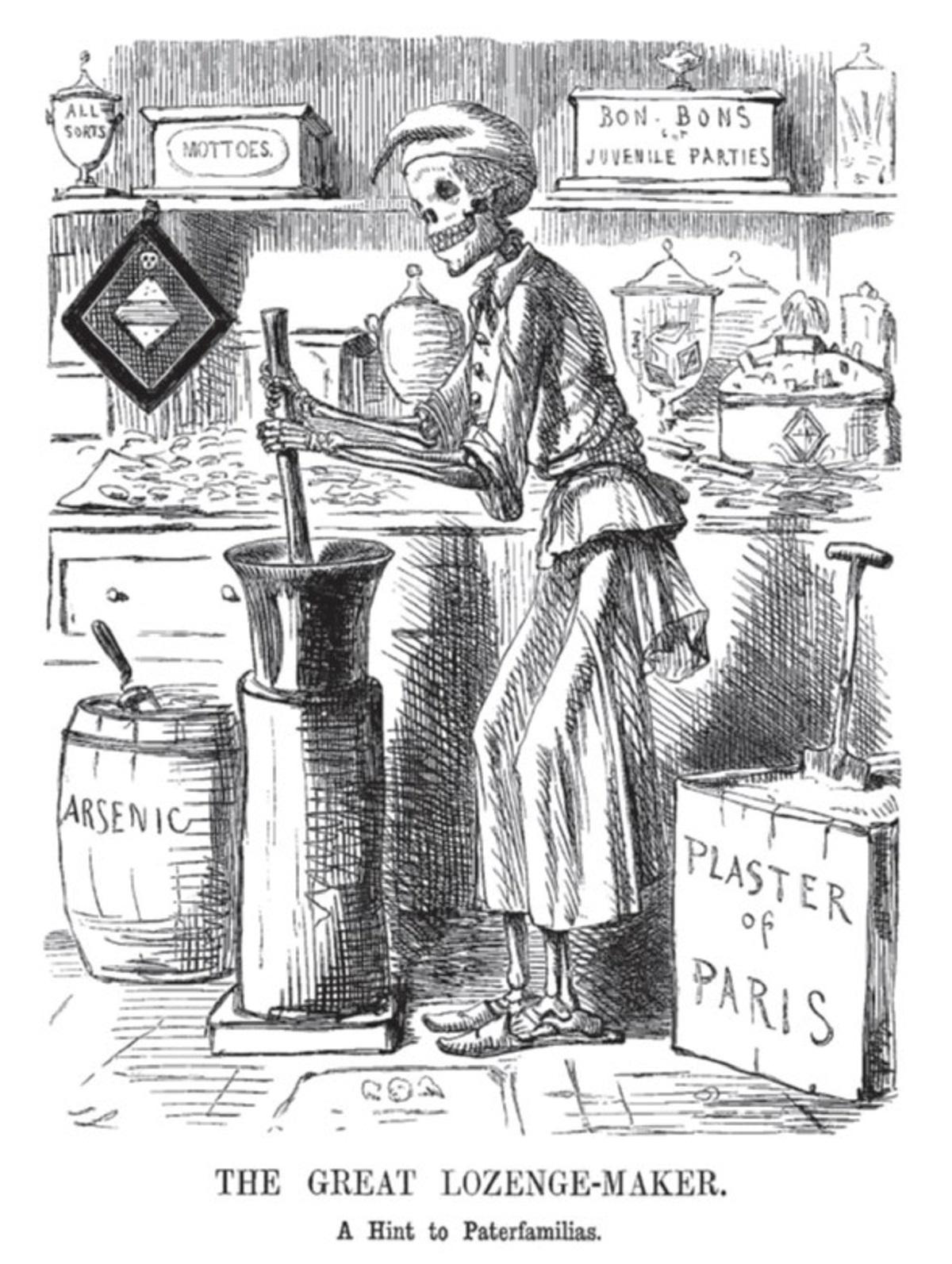

He focuses on it in a chapter on ‘adulteration’ - an adulterant being ‘a hostile matter found in substances such as food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, fuel or other chemicals that compromises the safety or effectiveness of that product.’

For centuries before the Bradford incident, sugar was extremely expensive and was called ‘white gold’, writes Chrystal. The government recognised the opportunities and taxed it severely: in 1815 the tax raised from sugar in Britain was £3million. To defray the costs of raw materials, sweet and chocolate manufacturers resorted to adulteration and their products were mixed with cheaper substances or ‘daff’. This was a concoction of harmless daff such as powdered limestone and plaster of Paris.

William Hardaker, known locally as ‘Humbug Billy’, sold sweets from a stall in the Green Market in Bradford, now the site of the Kirkgate Shopping Centre; his supplier James Appleton, the manufacturer of the sweets - including peppermint humbugs - used daff in his sweet production. It was supplied by a druggist in Shipley.

‘Tragically’, writes Chrystal in his illustrated book, ‘12lbs of arsenic trioxide were sold instead of the harmless daff. Both daff and arsenic trioxide are white powders and look alike; the arsenic trioxide was not properly labelled and negligently stored next to the daff.’

The mistake went undiscovered during the manufacture of the sweets: Appleton combined 40lbs of sugar, 12lbs of arsenic trioxide, 4lbs of gum, and peppermint oil, to make 56lbs of peppermint humbugs.

Hardaker sold the poisoned sweets from his stall, with devastating results. All involved in the production and sale were charged with manslaughter, but no one was convicted.

Good did, however, come of the tragedy - new legislation to protect the public in the form of the 1860 Adulteration of Food and Drink Bill which changed the way in which ingredients could be used and mixed. The UK Pharmacy Act of 1868 saw more stringent regulations regarding the handling and selling of named poisons and medicines by pharmacists.

The abolition of the sugar tax in 1874 meant that sugar became affordable and daff was no longer used.

Other cases of adulteration are referred to in the hardback book, which charts the development of sweets -the earliest recorded examples being based on honey not sugar.

Of course it is sugar upon which the industry developed and thrives. As Chrystal writes: ‘without sugar there would be no such thing as sweets as we know them today.’

By the seventh century Persians were operating sugar refineries. In ancient India pieces of sugar were produced by boiling sugar cane juice and eaten as ‘khanda’, the first form of candy.

The book looks at the use of sweets for medicinal purposes - their use to soothe the throat can be traced back to 1000 BC - and the rapid growth of the confectionery industry.

One area which is often overlooked but significant in the growth of the industry is slavery. The use of slaves on sugar plantations involved some of the best-known sweet and chocolate manufacturers, who professed to be opposed to the barbaric practice. ‘All the while the chocolate companies were facing increasing criticism and accusations of hypocrisy, led by the London Standard of 26 September 1908 exposing that ‘monstrous trade in human flesh...the very islands which feed the mills and presses of Bournville.’

Shockingly, slavery continues to be tolerated in the confectionery industry, with 2.3 million children working in the cocoa fields of Ghana and Cote d’Ivorie, helping to sustain many leading manufacturers. Good work is, however, being done by Nestle and others, writes Chrystal, into increasing action against Good work is, however, being done by Nestle and others, writes Chrystal, into increasing action against child labour and expanding a cocoa sustainability program.

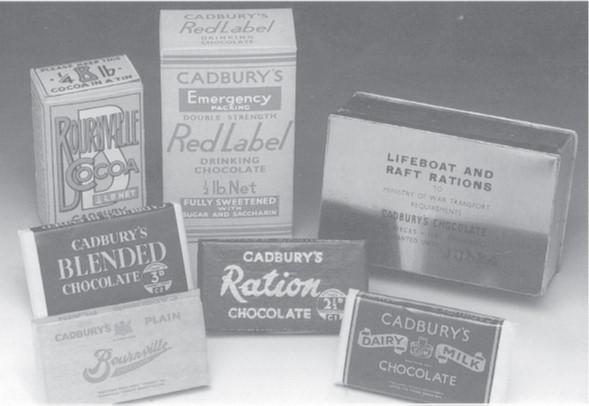

The history of Yorkshire manufacturers Nestle - formerly Rowntrees - Terry’s and Craven’s are covered in the book, which contains a chapter on ‘special sweets’, appraising old favourites still popular today such as gobstoppers, dolly mixtures, liquorice, bulls’ eyes and, of course, humbugs.

The History of Sweets is published by Pen and Sword (pen-and-sword.co.uk) and costs £25.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here