THE discovery of a cache of petrol bombs in Little Horton made front page headlines in the Telegraph & Argus in July 1981.

Days later, 12 Asian men appeared before Bradford magistrates charged with conspiring to cause damage or destruction by fire or explosion with intent to endanger life and with conspiring to cause grievous bodily harm.

The men pleaded not guilty, claiming they were acting in self defence, to protect their community against a march they believed was planned by British fascists in Bradford. The petrol bombs weren’t used, as the march didn’t take place.

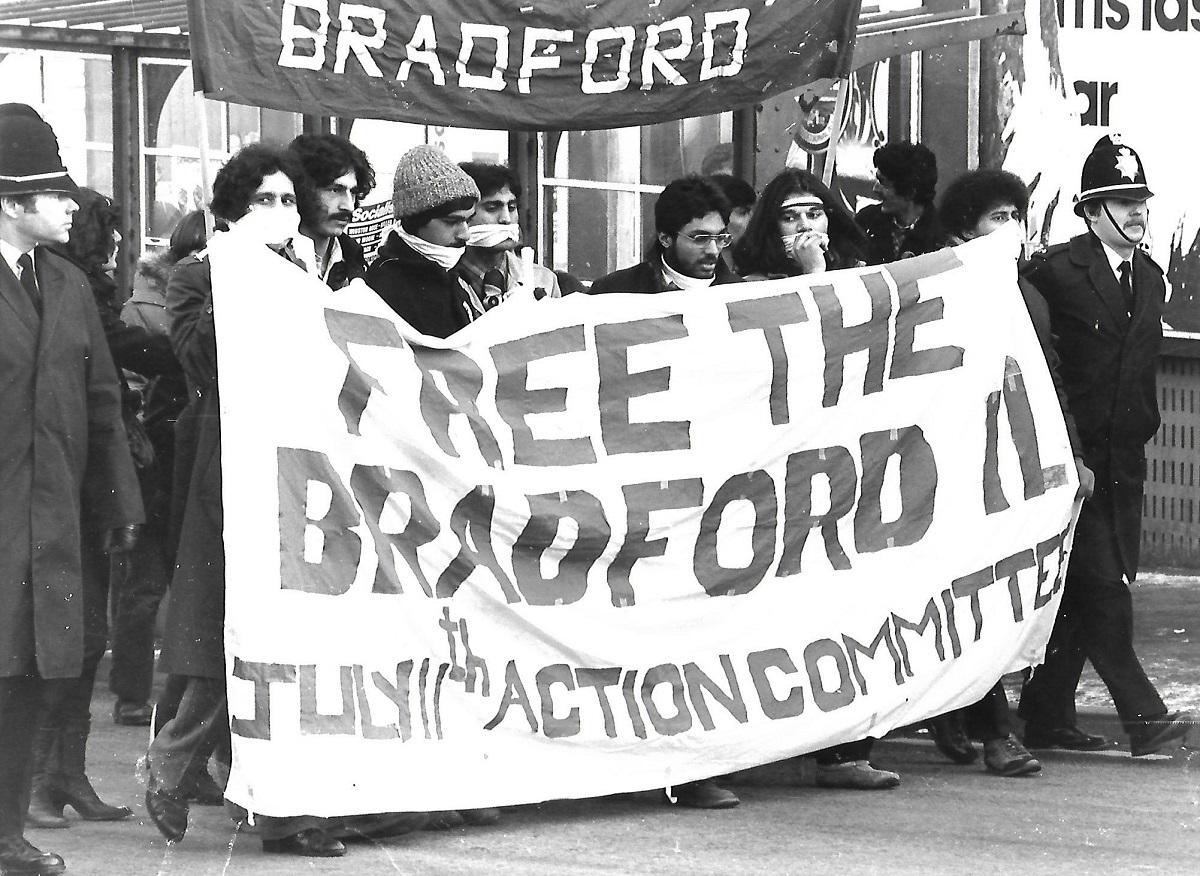

What followed was a high profile campaign and a series of demonstrations to free the men, who became known as the ‘Bradford 12’. They were eventually acquitted, after what was called by some journalists and commentators ‘the trial of the decade’, which took place at Leeds Crown Court in May 1982.

Influenced by the Black Power movement of America, the Bradford 12 campaign was widely supported by organisations including feminist and student groups, religious organisations, trade unions and the Socialist Workers Party.

The Bradford 12 were from a variety of backgrounds including Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Christian. They were members of the United Black Youth League, a splinter group from the Asian Youth Movement, established to defend communities from rising racist attacks taking place on the streets of 1970s Britain.

On January 18, 1981 13 black teenagers died in a house fire in New Cross, South London, in a suspected racist attack. On July 2, 1981 Parveen Khan and her three children died after petrol was poured through her letter box in London’s East End.

A T&A report from August 5, 1981 on the Bradford men’s appearance before city magistrates said “two crates containing 38 milk bottles partly filled with petrol with a wick in the neck of the bottles” were found by police in the grounds of Horton Hall. Nearby was an upturned crate “which had apparently been used as a table to make the bombs and three empty oil cans”.

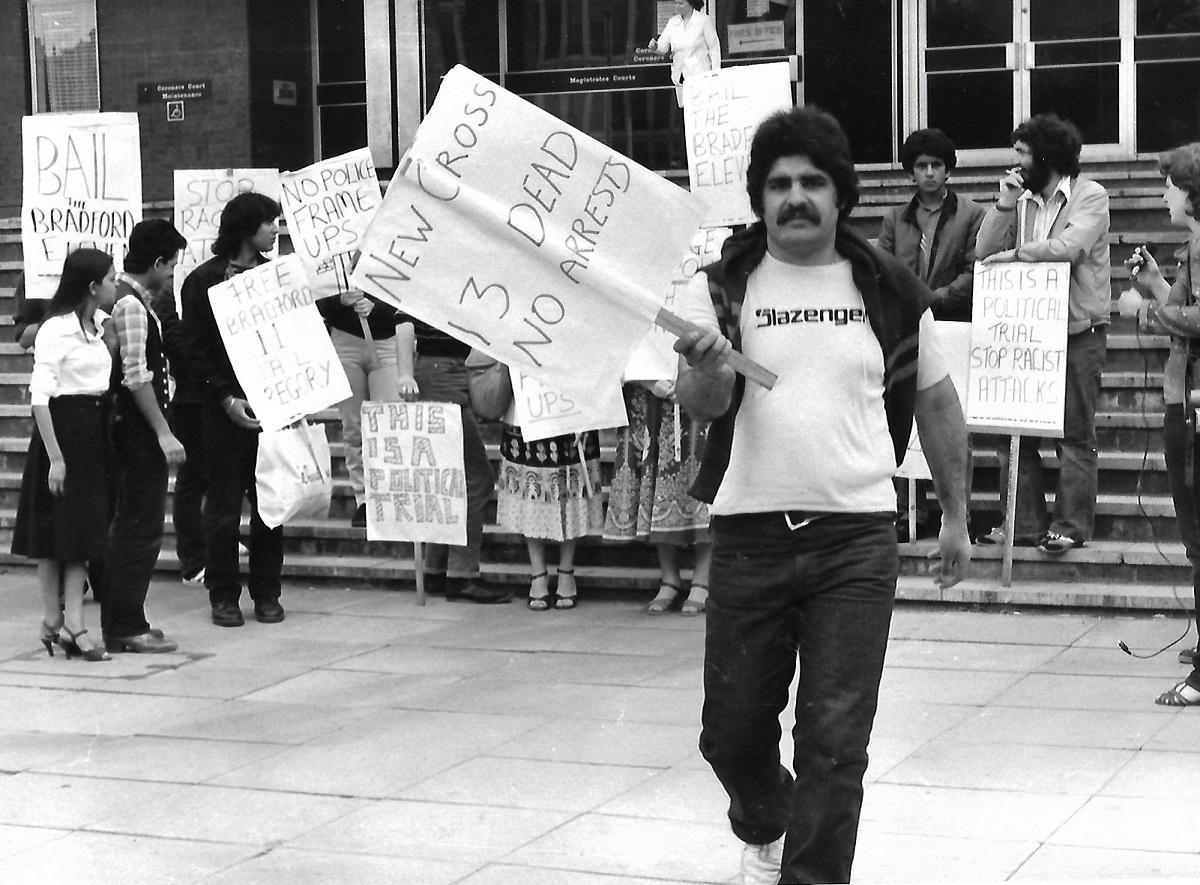

Alongside the report was an article on a demonstration outside the court, with the headline ‘Frame-up’ claim’. Courtney Hay from the July 11 Action Committee, which organised the protest, told the T&A there was concern at the way the men had been arrested. The committee claimed the men had been taken to the police headquarters in the Tyrls and “subjected to constant and prolonged interrogation and physical harassment”.

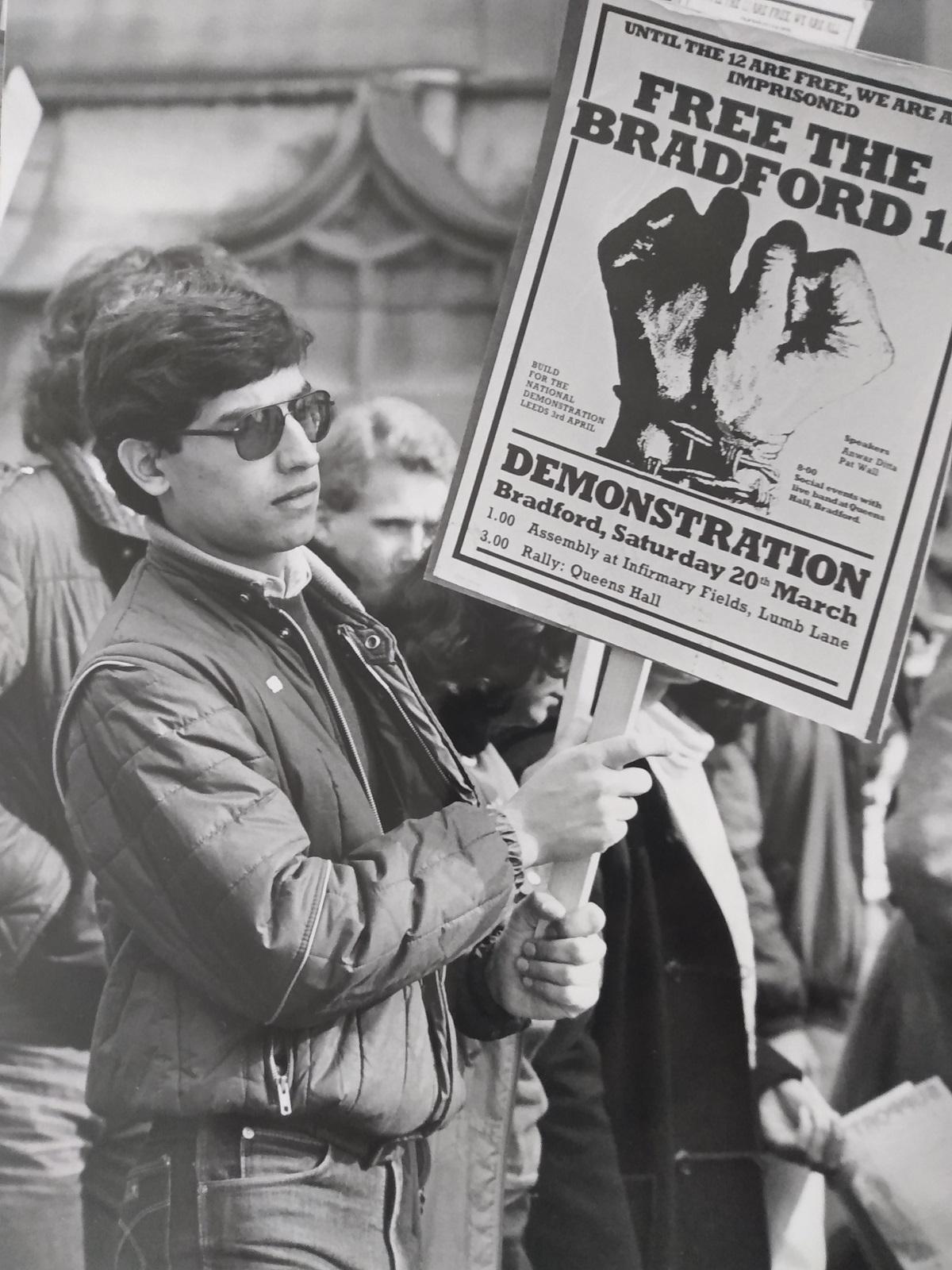

In March 1982, protesters shouting “Free the Bradford 12” and “Police conspiracy” marched through the city centre to a rally at Queens Hall. At the rally, Pat Wall, then president of Bradford Trades Council, and later the MP for Bradford North, objected to the detention of the 12 by police for more than three months in prison. A national demonstration supporting the Bradford 12 took place the following month.

At their trial the men said they were forced to defend themselves against a feared skinhead fascist march because, in the previous five years, the police had failed to respond adequately to racist attacks. Echoing the actions of the Mangrove Nine, a group of British black activists tried for inciting a riot at a 1970 protest in Notting Hill, the Bradford 12 challenged the make-up of the jurors. Defence barrister S Kadri applied for the original list of 75 jury summonses to be scrapped because it included only six people from ethnic minorities.

The T&A reported on April 24, 1982 that Mr Kadri “asked that a new set of 75 summonses be sent out to include people living in the large Asian community in Bradford. “He told the court: ‘An all-white jury could not be seen to understand the sentiment and fears of Asian people in Bradford. We do not want the Asian community to say that this jury is fixed’.”

But Judge Christopher Beaumont dismissed the plea, saying it was “beyond his power before the trial to interfere in any way with the constitution of the jury panel”.

On June 16, 1982, at the end of a 31-day trial, the men were acquitted. The T&A reported that the verdict was announced “among scenes of extraordinary celebration”.

After the trial Bradford 12 spokesman Tarlochan Gata-Aura told the T&A: “We have just shown to the courts that black people have the right to defend themselves by any means they feel necessary.”

The acquittal of the Bradford 12 was seen as a significant victory in highlighting the right of a community, rather than an individual, to defend itself.

Reflecting on the trial, Clare Dyer wrote in the T&A in June 1982: “The defence argued during the trial that the Asians were in the same position as women who went armed with scissors during the Yorkshire Ripper’s reign of terror”.

She added: “The verdict holds a clear message for the police. Unless endangered communities are given equal protection, juries will not necessarily blame them if they take the law into their own hands”.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here