IN the first of a two-part series looking at the changing face of nursing in Britain, Dr Sid Brown, Public Governor of Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, writes:

FOR many of us, the NHS is not just a treasure but the nearest we come to having a legitimate national religion. We’’re not the first to appreciate those who care for us. The first century Roman philosopher Cicero felt ‘in nothing does mankind nearly approach the gods than in giving health’. That’s all very well but his dated language is in need of appropriate gender re-wording when it comes to contemporary challenges for our NHS.

As a Public Governor of our NHS Care Trust one of my most memorable early experiences was to attend our Step Into Nursing recruitment event at Valley Parade. It was reassuring to be with so many caring folk contemplating this career, not least because quite a few young men and varied ethnic groups were present. Things were very different in the early years following the establishment of the NHS in July 1948. Certainly the role of nursing was, throughout those post-war formative years, accurately presented as predominantly ‘women’s work’ exemplified by the potent vision of Florence Nightingale doing her rounds in the Crimean War. ‘The Lady with the Lamp’ featured prominently in nursing graduations I attended in the United States in the 1970s.

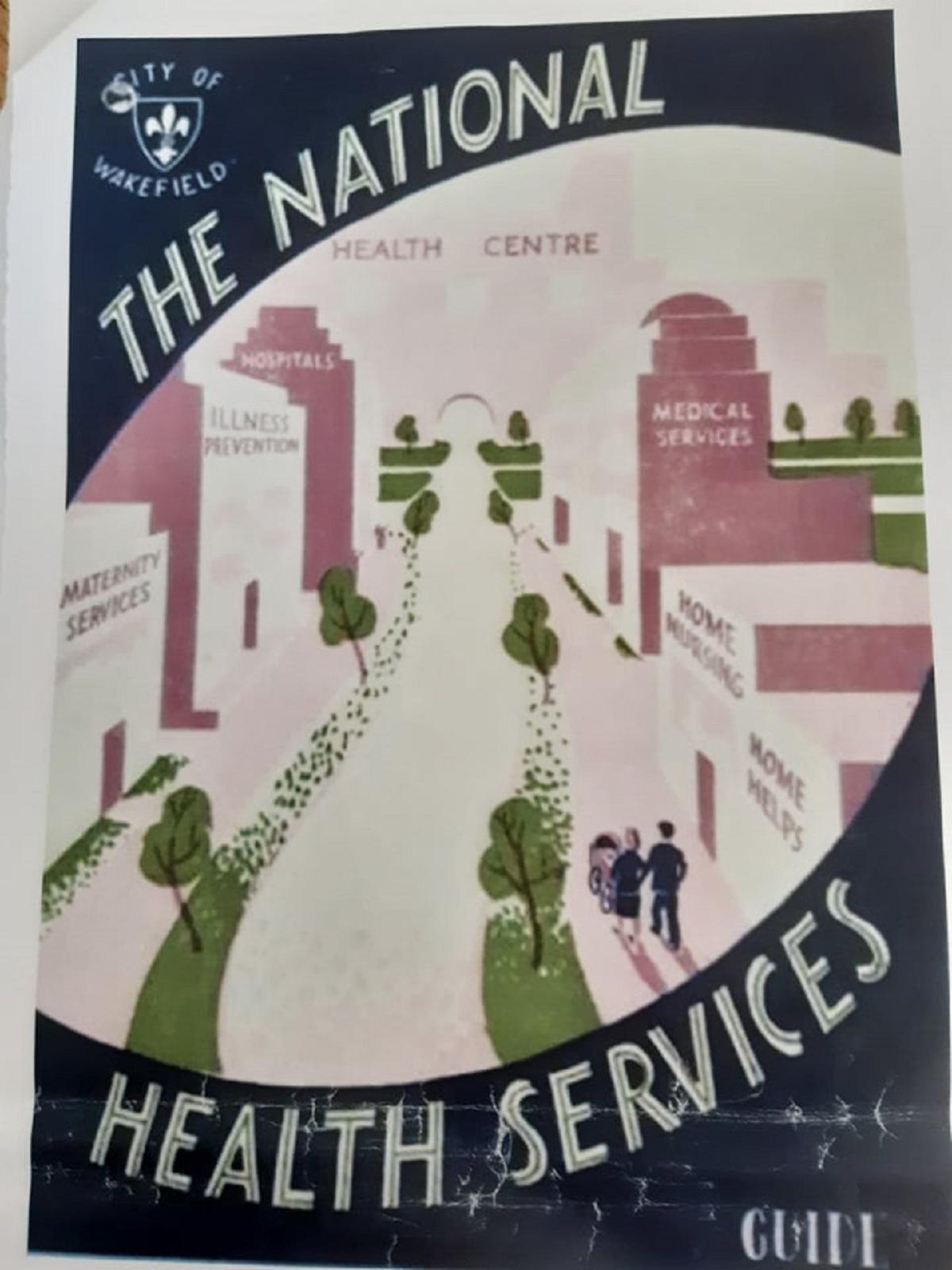

An iconic image indeed, but again now seriously outdated. Yet there’s nothing at all old-fashioned about one early NHS poster from 70 years ago stressing ‘Immunisation is VITAL’ for it’s bang on target in our present situation. Consider another poster describing ‘The National Health Services’ available in Wakefield; so typical of a new optimistic tone associated with universal healthcare. Such impressive campaigns were the result of local councils working effectively with the NHS Central Council for Health Education.

This post-war generation latched onto pithy official messages with catchy phrases such as ‘Coughs and sneezes spread diseases’ and references to prunes being ‘nature’s little helpers’ but, unsurprisingly, that ‘glorious Trinity’ of ‘bulk, bowels and stools’ dreamed up by the Radio Doctor Charles Hill never really caught on during that bleak 1946-1948 period prior to the passing of the NHS legislation introduced by Attlee’s government.

It’s generally agreed the grim memories of so-called ‘medical provision’ in the 1930s and impact of the Second World War were vital catalysts in the establishment of a comprehensive health service caring for us free at the point of delivery. Yet the ground had already been well prepared in a weary population’s minds. Upbeat newsreels during the conflict depicted nurses as heroic and remarkable which of course they had proved to be.

Hard-pressed austerity audiences could enjoy Anna Neagle playing both Florence Nightingale and the tragic Edith Cavell. In each portrayal, Neagle was the epitome of virtue, such performances must have brought much-needed reassurance during those difficult, drab years to an exhausted population and no doubt were viewed enthusiastically by the NHS’s first cohorts of nurses.

What comes through in one young doctor’s memories of the exhaustion yet enthusiasm of NHS nursing staff at this formative time is the frequent gulf between image and reality in the profession during these demanding times. This is beautifully captured in the optimism of brightly coloured recruiting posters from the period. With their emphasis on nursing as a ‘worthwhile career for women’ 1950s recruiting drives are fascinating. One example utilizes a young nurse looking winsomely towards a better future. This ‘modern nurse’ is portrayed far less ‘starchy’ than her predecessors as is her uniform so delightfully recreated in the 2012 London Olympic opening ceremony. At the time images of nurses all seemed far too glamorous. Recruiting portrayals never shows them exhausted or even wearing glasses or being over 40! In posters they are often holding babies, receiving awards at Buckingham Palace or encouraged to work with the so-called ‘mentally handicapped’ (frequently post-traumatic stress disorder patients) who’d suffered in wartime service.

By the end of the decade slogans such as ‘You Have It In You’ and ‘Come Back To Us’ geared to returners appear increasingly, coinciding with the long overdue end to the ludicrous ban on married women. Posters started to show more mature, experienced nurses. Yet a shortfall remained. Determined recruitment drives were commenced in Commonwealth countries with the easing of citizenship restrictions and by 1968 30per cent of student nurses in UK were from the Commonwealth, particularly the West Indies. Young Daphne Steel came from Guyana in 1951 and became a Matron in 1964 at St Winifred’s Hospital, Ilkley - the first member of her community to achieve this status. Her significance, like Mary Seacole, one of Nightingale’s colleagues, offers parallels despite these two remarkable nurses separated by a century and has deep implications for NHS recruitment and staffing levels to this day.

* Views expressed are solely those of the writer, not NHS Ttrust.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here