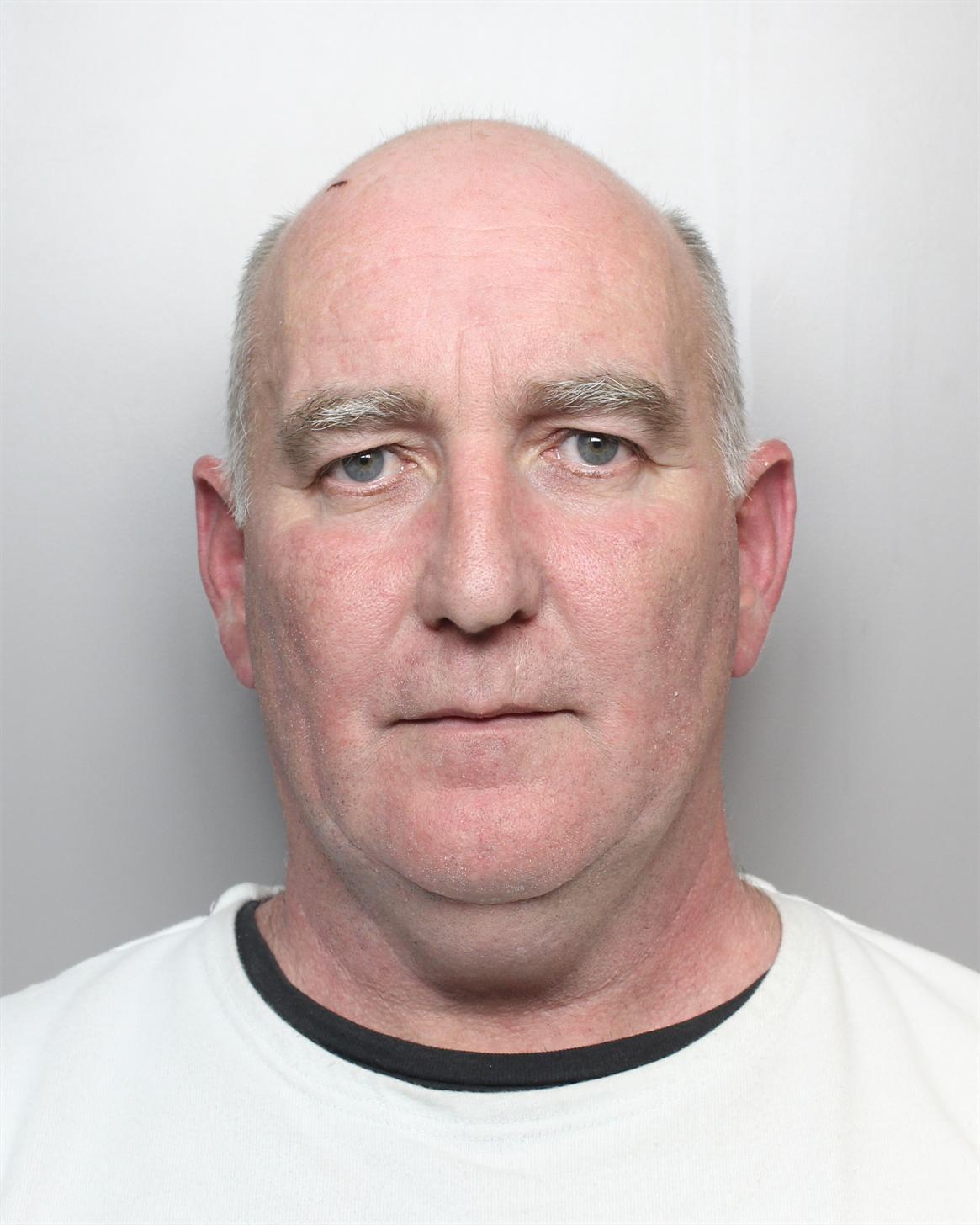

The founder of the Little Heroes Cancer Trust has been jailed for 20 months for stealing from the charity and putting its money into bank accounts in his name.

Colin Nesbitt, 60, of Kent Road, Bingley, was found guilty by a jury last month of four of-fences of fraud and one of theft between 2009 and 2015.

Today, Judge Jonathan Gibson told him he had betrayed public confidence in the whole charities sector.

“You were dishonestly mingling personal and charity expenditure,” he said.

But it would be unjust to sentence Nesbitt on the basis of “the headline figures on the indictment.” Much of that money was spent on Christmas toy drops, staff wages and cost of the premises.

Judge Gibson continued: “What you did was in breach of a very high degree of trust and responsibility. In additional to the financial loss, you betrayed the public and public con-fidence in the charity and the whole charities sector.”

Judge Gibson accepted that Nesbitt’s intention at the beginning was to give a child in hospital with cancer a toy, and many ordinary members of the public gave to the trust through its Firewalks.

But he created a situation with no oversight into what he was doing. He did not ensure any proper financial controls and relied heavily on cash transactions.

The jury found he had “creamed off” some of the money for himself by putting it into his accounts.

Judge Gibson said he was satisfied that Nesbitt did not take all of the money alleged in the charges. But he bought cigarettes and clothing that was not charity expenditure.

Nesbitt was convicted of two charges of abusing his position as director of the Little He-roes Cancer Trust by transferring monies and/or depositing cash and cheques belonging to the trust in sums of £44,000 and £181,230 into accounts in his name, making dishon-est loans in the sums of £16,000 and £5,000, and stealing £87.080 belonging to the Little Heroes Cancer Trust.

Prosecutor James Lake told the court today that he had previous convictions for benefit fraud, forgery and burglary.

Mr Lake said a fraud on a charity undermined people’s trust in such organisations. Nes-bitt betrayed the givers and abused the confidence of those involved in the trust.

It was hard to imagine a worse breach of trust, he said.

Attempts had been made to rebrand the charity but they had failed and it closed in 2016.

Matthew Donkin, Nesbitt’s barrister, urged the judge not to send him to prison.

He had been spat on when shopping locally following his convictions. They were never going to leave him; they were “a public and obvious punishment.”

Shame and scandal would follow him much longer than any prison sentence, Mr Donkin said.

The prosecution could not say what the actual loss amounts were. A significant amount of the money was spent on charity’s expenditure.

Although Nesbitt had “damaging and serious offences” on his record most were committed when he was a much younger man. He had been out of trouble since 2001 and began the charity “with the best intentions and in good faith” after seeing his grandson was unwell.

Mr Donkin conceded that Nesbitt’s culpability was high but overall his conduct was not that of a sophisticated, scheming criminal.

The charity had relied heavily on cash expenditure and cash transactions and it was impossible to say what went missing and what was spent for legitimate purposes.

He was the carer for his grandson who had been dealt “a severe hand” with his se-rious illness.

“There’s no question that Mr Nesbitt did a great deal of good. He was there when people were suffering and struggling and in a great deal of need,” Mr Donkin said.

During the trial, the jury heard that the trust was founded in 2008 to give toys to chil-dren in hospital with cancer after Nesbitt’s own grandson became ill with the disease.

The toy drops started at St James Hospital in Leeds but spread to other hospitals across the country. Fundraising Firewalks were then held nationally to raise money.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article