MUSCA VOMITORIA: even its proper Latin name couldn’t describe the larval stage of the common bluebottle any more aptly. Because they eat decaying flesh, blue bottle flies in the house sometimes indicate a decomposing animal in an attic or wall space. They are a reminder of the unpleasant side of life and death that we would rather ignore or forget.

Dictionaries describe Musca vomitoria as ‘a large and troublesome species of blowfly’, and troublesome was the perfect description of the effects of these creatures on local people in and around Wrose from early in the 20th century.

And all, initially, for the sake of anglers!

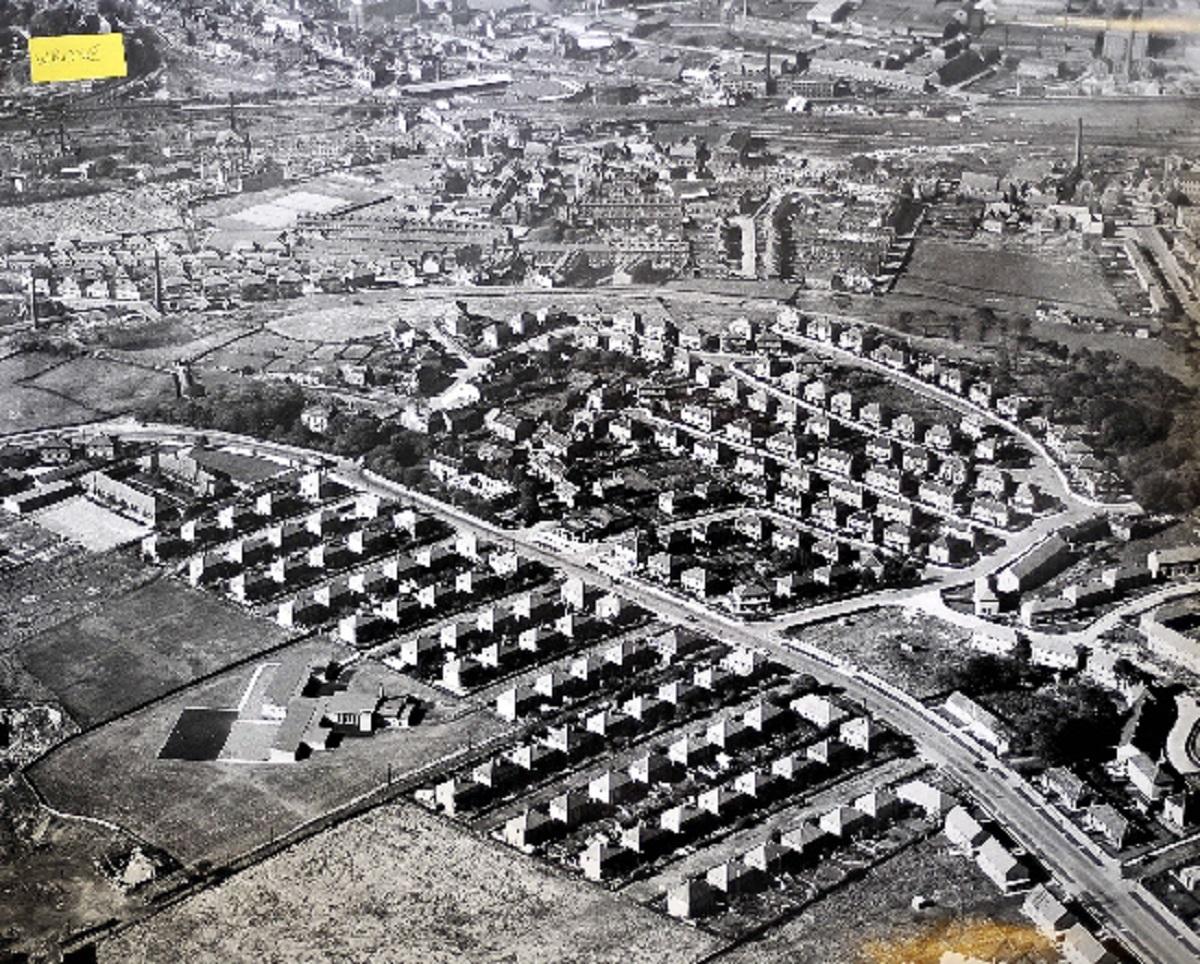

The maggot farm in Wrose was a small business belonging to the Hainsworth family. It was located by the Catstones Wood, in an area of rough land and smallholdings, accessible only by cart tracks.

The farm, with its putrid-smelling shed-like buildings, wasn’t a major problem until the second half of the century. Then the housing developments built for Shipley’s fast expanding population began to creep ever closer.

Meanwhile the farm was in full production, breeding the larvae to supply Britain’s anglers, zoos, laboratories and bird-keepers with possibly the tastiest food or bait they could want. The Hainsworth family’s maggots had a widespread reputation for quality, not just locally.

But the pungent ammonia-like stench given off by large quantities of maggots was not to the liking of people moving to live in the new houses around the farm. Add to that the foul smell of rotting meat - which was food for the maggots - wafting on windy days over areas beyond Wrose itself - Idle and Thackley included - and mass breakouts of bluebottles escaping from their sheds. Unsurprisingly, the farm became the focus of complaints.

In 1968 the Telegraph & Argus reporter Jim Appleby visited the farm to investigate the grievances of the local householders.

He described what he found in vivid detail: “You go into the breeding shed. Immediately the heavy ammonia smell in the air catches the throat and wrings tears from the eyes.

“In stone stalls on both sides of the shed, maggots in their thousands gorge themselves on fish and meat ... ten days later they are ready to riddle off into sawdust filled troughs in another building for dispatch’. “

He continued: “But, for a maggot farm, it was well-run and hygienically clean and operating within the rules of public health.”

A 1965 T&A news article reported that more than 30 residents petitioned Shipley Council complaining of flies and “objectionable smells” coming from the maggot farm at Catstone Wood, Wrose: “The petition described the family business, which had been set up 60 years ago, as detrimental to the neighbourhood”.

There was, however, an unexpected beneficial side to the existence of these maggots. Bradford had always had a problem with high rates of tuberculosis, particularly amongst the poorer of its people. These were the people who lived in appallingly bad, overcrowded slums amongst all the smoking chimneys of the great woollen mills for which the city was world famous.

There were a lot of folk remedies and quack medicines that promised to cure the disease, but tuberculosis continued to kill, relentlessly, as many as 10per cent of the population throughout the 19th century.

Many of the folk cures were based on the need for a change of air. And since few people in Bradford could afford a lengthy visit to a sanatorium in Switzerland’s mountains, cheap alternative therapies were needed. And, for a short and cheap change of air, where else but Wrose?

As a researcher in the 1960s reported:

“... in the Wrose area of Bradford/Shipley some at least of the old inhabitants believe that the vile smell emanating from a local ‘maggot-farm’ is good for sufferers from tuberculosis, and I have been told by one person that, during the Great War, platoons of soldiers were marched through the buildings in which the maggots were reared in order to strengthen their resistance to the disease.

If that precautionary measure failed, soldiers returning from the battlefields with tuberculosis were prescribed a regular two hour spell in the maggot breeding shed, the theory being that ammonia was good for cleaning the lungs.

“It was not a pleasant remedy - two hours of sitting in a hut full of maggots, after all the soldiers had gone through on the battlefield, must have felt more like a form of torture than a cure. But another source, writing of the same period, mentions the even worse remedy of eating maggots that could be inflicted upon soldiers.”

But many of the folk remedies for tuberculosis - in the past more commonly called phthisis or consumption - were based on the assumption that this type of vapour treatment for various lung disorders was beneficial .

There were tales of TB sufferers being made to “breathe the breath of horses, mules and donkeys” or children being held over a privy or commode or ‘taken to a pig sty before dawn and made to “bite into the hog trough” or being held over a steaming manure pile. Spending nights lying in a cow byre with the cattle was also a popular remedy.

All of these practices seem to have rested on the importance of a change or exchange of air between the animal and the human. Most of them demonstrate how desperate people were to be cured of what was so often a fatal disease.

It is worth noting that when, in the late 1940s, a person who had recently moved into the Wrose district tried to rouse local opinion against the maggot farmer on the grounds that his ‘farm’ was a danger to health, he received very little support for his campaign. The Shipley Times stated that: ‘The report of the Area Planning Officer upon his recent inspection of the premises was submitted, and it was resolved that no action be taken in the matter’.

Had the people of Wrose become immune to the nauseous smell, or were they perversely proud of their curious local farming enterprise?

Were they even still paying a visit to the farm when they felt the need for ‘a change of air’?

The farm still existed when in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I occasionally worked in the area, and if the wind was in the wrong direction the stench was terrible.

And if I had to send staff out to work in the thereabouts they were sometimes very reluctant to do so. I think it was closed down in the 1970s.”

* Maggot farms continue today, often using offal or meat in large containers covered with chicken wire to prevent animals from feeding on it. Flies deposit eggs on the offal and meat and maggots hatch and consume it.

The containers are then filled with water so the maggots start to float, and they are then harvested and sold for animal feed and fishing bait.

* Do you remember the Wrose maggot farm?

Email emma.clayton@nqyne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here