MARTIN Greenwood’s new book Every Day Bradford provides a memorable story for each day in the year about people, places and events taken from the district’s rich history - from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Bradford-born and bred, Martin has been constantly surprised by what he has discovered in his research into his home city, which was stimulated by researching his first book, about his grandfather, Percy Monkman: An Extraordinary Bradfordian.

We have invited Martin to write a regular feature about some of the stories he has uncovered that have surprised him the most.

We start with the first of two remarkable ‘rags-to-riches’ stories from the humblest of upbringings in Bradford: Joseph Wright.

How did someone born into poverty who was illiterate until the age of 15 end up as a highly respected Oxford professor of philology?

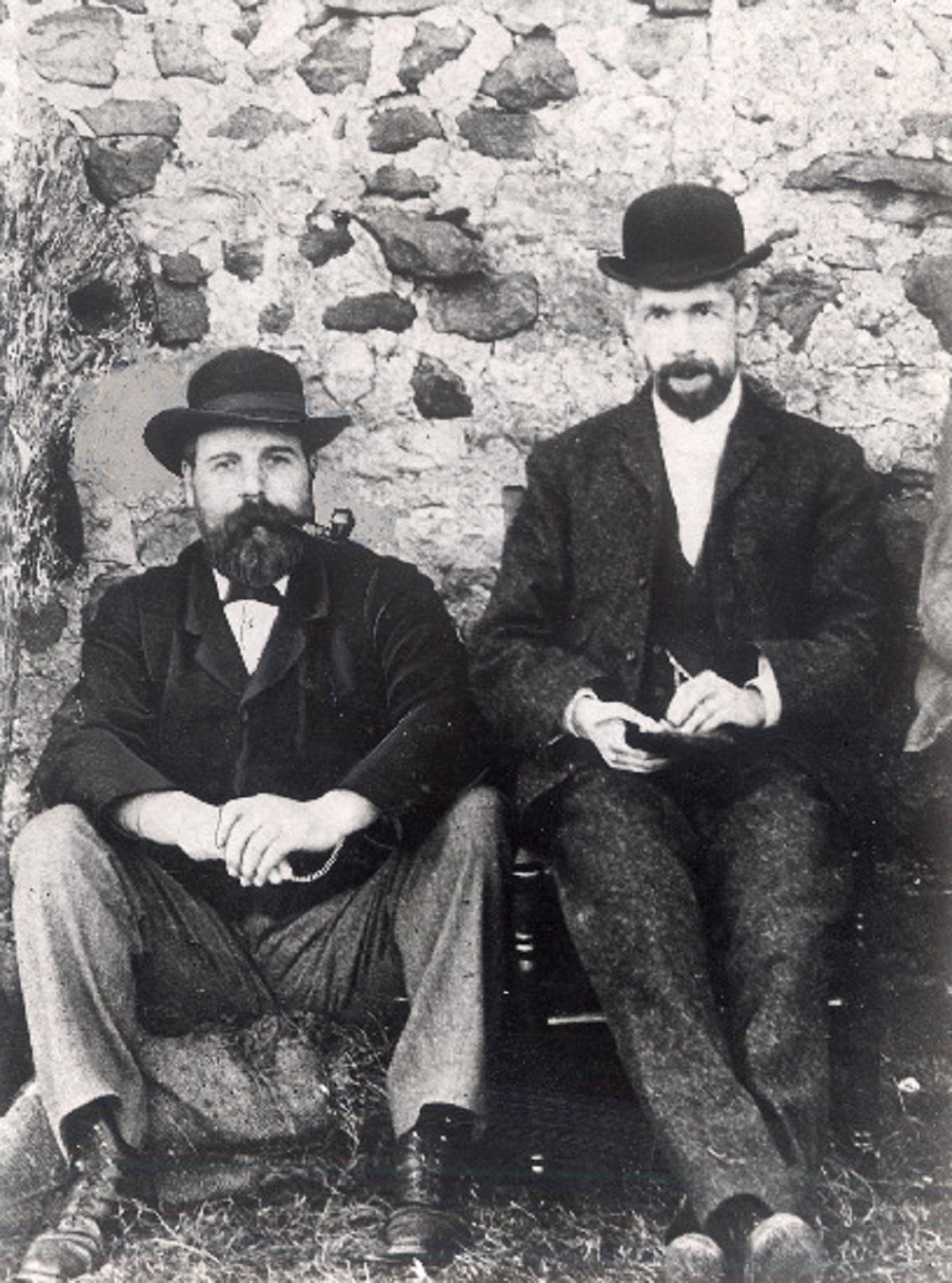

‘I’ve been an Idle man all my life and shall remain an Idle man till I die’. These were familiar words from Professor Joseph Wright (1855-1930) to his Oxford friends. Those hearing them for the first time might have been mystified, for he had a prodigious capacity for hard work and a passionate commitment to his subject.

Wright came from Idle on the outskirts of Bradford. His Oxford home was named after Thackley, his birthplace, in the township of Idle. His life was an amazing journey from one Thackley to the other.

His childhood was spent in absolute poverty. His father was a ‘ne’er-do- well’, wasting what little he earned on alcohol and was frequently absent. His mother was left to fend for herself and bring up her young family, first an illegitimate boy by another man, and then four small sons, the second being Joseph, by the man she married.

For a while they had to live in the workhouse at Clayton, but Joseph’s mother was determined to overcome her difficulties and make the best of things for her boys. After a spell in a one-room hovel in Thackley, she moved into a cottage at Windhill, and she earned a pittance washing and cleaning for others. Joseph started part-time work at just six-years-old as a ‘donkey-boy’ at a local quarry, driving a donkey-cart carrying quarrymen’s tools to be sharpened at the local blacksmith’s, and then as a ‘bobbin doffer’ at Salt’s Mill, replacing full bobbins from the spindles of a spinning machine.

Despite the difficulties Wright was resilient, self-motivated and entrepreneurial, earning extra where he could. He soon became the family’s breadwinner. He moved to another mill at Baildon Bridge and then became apprenticed as a woolsorter. Through his efforts the family was able to move to a bigger house in Windmill.

Although Wright had some very basic part-time schooling at Salts Mill, he did not learn to read properly until aged 15. Spurred on by seeing his workmates read newspapers in their lunch break, he slowly taught himself to read.

Increasingly fascinated with languages, he started evening classes first at a small night-school in Windmill and then at Bradford’s Mechanics Institute - a round trip of six miles to walk learning French, German and Latin, as well as maths and shorthand. When he turned 18 he even started teaching and charging colleagues two pence a week.

Now a woolcomber, as a 21-year-old he had saved enough to undertake a term’s study at Heidelberg University, returning later to study for a doctorate in philosophy. In 1888 he took up a teaching post in German at Oxford University. Here he soon became a lecturer in German philology and a few years later professor.

His academic reputation was based mainly on being the first editor of the English Dialect Dictionary. Already a contributor, he was approached by its founder to take over this huge task started in 1872. After nine years’ more research, the publication, 5,000 words over six volumes, took him another nine years (1896 to 1905). The dictionary contained 100,000 words and half a million quotations. He also undertook the funding of this exercise through subscriptions, itself a massive undertaking.

As first JRR Tolkien’s philology tutor, Wright became his close friend after World War One. He was an important influence in the life of Tolkien who was to invent his own medieval language of Elvish for his classic Lord of the Rings. In the 2018 film Tolkien Wright, played by Sir Derek Jacobi in a cameo role, reveals how important that influence was.

His devoted wife Elizabeth who published a biography two years after his death recounted some heart-warming visits back to Bradford as he was making his way in academia. For example, in 1901 he was made President of the Salt Schools in Saltaire. He gave his presidential address in the very place where, as a child 30 years before, he had worked as a ‘half-timer’.

‘Then, there was not a good night school in the whole of Shipley where a working man could learn anything beyond reading, writing, arithmetic and book-keeping, and yet now in a little place like Windhill there was an excellent night school where students learned six languages’. His mother sat in the middle of the front row, ‘with a look of radiant joy on her face, and tears in her eyes as she gazed upon her son in that hour of bliss’. In a vote of thanks to loud applause, the chairman ‘congratulated her upon having such a son, just as he congratulated the son upon having such a mother.’

Wright had indeed made a long journey from Idle donkey-boy to renowned Oxford professor.

* Article adapted from Every Day Bradford, Martin Greenwood (2021). Available from Amazon, Waterstones, Blackwells, WH Smiths and Salts Mill.

Sources: The Life of Joseph Wright, Mrs EM Wright (1932); From Donkey-Boy to Oxford Don, Christine Alvin (2020) in The Antiquary; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

* Every Day Bradford, which took Martin Greenwood two years to complete, is a fascinating profile of the district’s movers and shakers - from Samuel Cunliffe Lister to Dynamo - social reform, industry, immigration, sport, architecture, the arts, and much more.

Writes Martin: “There are many Bradford books; general histories, specific themes, biographies. I didn’t want to attempt a conventional history. New topics for each day convey the diversity of history and encourage readers to learn more. A calendar of stories makes it easier to put the book down without losing the thread.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here