MRS Fanny Hertz is probably not a name that is instantly recognisable, and possibly not commonly discussed in 21st Century Bradford.

However, in the 19th Century Fanny was a woman ahead of her time. Born in Hanover, Germany, in 1830, and related to Heinrich Hertz, famous physicist and discoverer of Hertz’ Rays, Fanny would become a leading light in the struggle for women’s education, and as such it is fair to say she can be labelled as a feminist.

In the mid 1870s she moved to London and spent the next decade dividing her time between Bradford and the Capital. Her husband, William David Hertz was a yarn merchant and mill owner, and before long their Bradford home would be transformed into an engine house of artistic and radical discussion. It was at this period in her life that Fanny became interested in science, through her friendship with Frederic Harrison. He was an advocate for Positivism, a philosophy that claims that true knowledge of the world can be derived through our senses from experience, and that society can be understood as governed by general laws, just like the natural world.

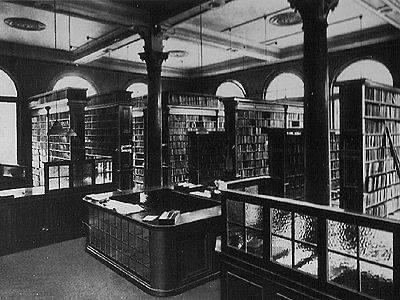

In the 19th Century, Mechanics’ Institutes began to be formed in towns and cities across the UK. They emerged from the Industrial Revolution, with a need to create a workforce with the skills to meet the demands of a mechanised workplace. In addition to practical skills such as care and maintenance of machinery, these institutes offered an education to working-class men. They housed libraries, ran classes and lectures and offered brilliant opportunities to those desiring self-improvement. Bradford Mechanics’ Institute was founded in 1832, meeting in various locations until in 1840 it moved to premises at the junction of Well Street and Leeds Road. It had amongst other things an exhibition space, meeting rooms, a reading room and cellars converted into a laboratory. In 1841 the Institute held an art exhibition attracting more than 140,000 visitors. As membership grew, new premises were opened in 1871. But a huge oversight was that these bastions of knowledge denied the same educational opportunities to women - an injustice that Fanny Hertz sought to rectify.

One of her major contributions to women’s education was the establishment of the Bradford Mechanics’ Institute for Working Women in 1857 which contained a library and several reading rooms. This was a groundbreaking endeavour, being one of the first institutes for women. It was important to Fanny that it offered classes that were inspiring and ‘first rate’ in order to create a love of learning and thirst for knowledge. Subjects included ‘the three Rs’: reading, writing and arithmetic, needlework, singing, history, and geography. For those who were interested there were more advanced classes in the sciences. The Institute also ran a penny savings bank.

This novel establishment attracted great interest; it had 600 young women enrolling, with 120 attending on a weekly basis. Fanny was invited to speak at a Social Science Congress in 1859. In her speech, ‘Mechanics Institute for Working Women with special reference to the Manufacturing Districts of Yorkshire’ she argued the value of education for its own sake, believing that this should be available to all, irrespective of class or gender, and that “all the obstacles to happiness in such a working community as Bradford would be proved when analysed to be more or less connected with the degradation of women, consequent upon ignorance.” Her speech was later published as a paper in the Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science. In this Fanny observed that girls who worked in factories lived a life that was “one perpetual round of monotonous ugliness”. A working day that began at 5am and often didn’t finish until more than 12 hours later. What was perhaps both shocking and unsettling for the Victorian reader was that these factory girls lived peripatetic independent lives, often living away from home in lodgings and moving around in search of work.

A shrewd, insightful woman, Fanny realised that these girls would relish an education that enabled them to remain independent. A Mechanics’ Institute was ideal since they were based on the concept of self-government. Moreover, the girls had a voice that would be heard as they were encouraged to vote in the election of committee members; they were, as Fanny stated “part proprietors and managers” having a say in how the Institute was run. And as they paid a membership fee of tuppence a week; giving the girls a sense of pride rather than feeling it was an act of charity. As Fanny was progressive in her outlook, she believed that students should be encouraged to make discoveries themselves - what we might refer to today as ‘student centred’ learning rather than the traditional ‘rote’ learning popular at the time. Significantly, the syllabus included a focus on health and the workings of the human body, which Fanny argued was essential not only to the girls’ understanding but also to the wellbeing of wider society.

Fanny was also instrumental in founding the Bradford Ladies’ Educational Association. An article from the Bradford Observer in 1868 suggests this Association emerged from discussions held at the Mechanics’ Institute that included Mrs WE Forster, wife of William E Forster, Liberal MP famous for the Elementary Education Act of 1870, Mrs Titus Salt, Jnr and the Rev Mitton. During these discussions it was suggested that the formation of such an Association offering tutoring in literary and scientific subjects would be beneficial for girls who had completed their schooling in advancing studies further. By providing this opportunity, it was felt that “a good deal would be done in elevating her from an unthinking schoolgirl into a ripe and intelligent woman”.

The Association would organise a series of lectures, and classes were run in subjects such as geography and English Literature. The overall aim was to develop young women’s understanding of the world - women who would then be in a good position to assist in the improvement of others. Fanny went on to represent Bradford on the North of England Council for promoting the Higher Education of Women in England, a key policy-making body. Founded in 1867, it was comprised largely of middle-class women, school mistresses and others with an interest in women’s education. One of its most significant achievements was the creation of examinations for girls over 18 that opened the door to an education at Cambridge University.

Fanny left in 1870 for London, leaving the legacy of being at the forefront of women’s education, creating opportunities for working and middle-class women and girls. No mean feat at a time when there were many obstacles for these students to overcome. In her paper The Anglo-Jewish Contribution to the Education Movement for Women in the 19th Century, Stella Wills described Fanny as standing for ‘all that was richest and best in art, music and intellectual life’.

Fanny was significant in shaping our city and improving the lives of so many, particularly poor, marginalised factory girls. For this pioneering work, her name deserves to be remembered today.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel