DR Margaret Sharp came to Yorkshire as Bradford’s first woman GP at a time when the medical profession included few women - in fact there was just one other woman doctor, working at St Luke’s Hospital.

Her name came to attention when researching the Eldwick Sanatorium. She was Dr Hector Munro’s original collaborator in founding the sanatorium in 1904 and the only person to remain in post throughout its life.

After Dr Munro left Bradford it was Dr Sharp who successfully applied to the West Riding County Council to convert the sanatorium company for the treatment of children only and, in 1914, the Eldwick Sanatorium School was established.

Margaret Sharp was born in 1871 in London, the ninth of 11 children. For over 25 years her father, Martin Sharp, was editor of The Guardian, the newspaper of the Anglican Church. Her mother was born into a military family in India.

Margaret recalled her father saying to his children, “I can’t leave you money but I can give you a good education which is a better gift. I have no use for the man or woman who doesn’t work.” The children clearly followed his advice. Margaret’s brothers included a barrister, architect, public school master, solicitor and clergyman and one of her sisters taught at Camberwell School of Art.

Margaret’s first degree was from Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. She entered the London School of Medicine for Women in 1894, graduating in 1900.

Her Bradford GP practice operated from her homes at Marlborough Road then Walmer Villas, Manningham. In 1939 she moved to a flat in Ashdown Court, Shipley. Dr Sharp soon made an impression in Bradford and although initially she was refused entry to the Bradford branch of the BMA, in time she was elected chairman.

Her experience with young people gave her a powerful voice frequently called upon. Addressing a meeting of the United Purity Campaign in St Jude’s School, to a gathering of women and girls, largely factory workers and shop assistants, she described cases where girls of 13-15 had lived ‘impure lives’ in Bradford and “suffered awful consequences”, Dr Sharp was emphatic on one point; “that the popular notion that men are different to women was an absolute lie. Men are quite as able to live a pure life as women. It would be of great advantage to the cause of social purity if girls would aim to get the respect of men rather than their admiration.”

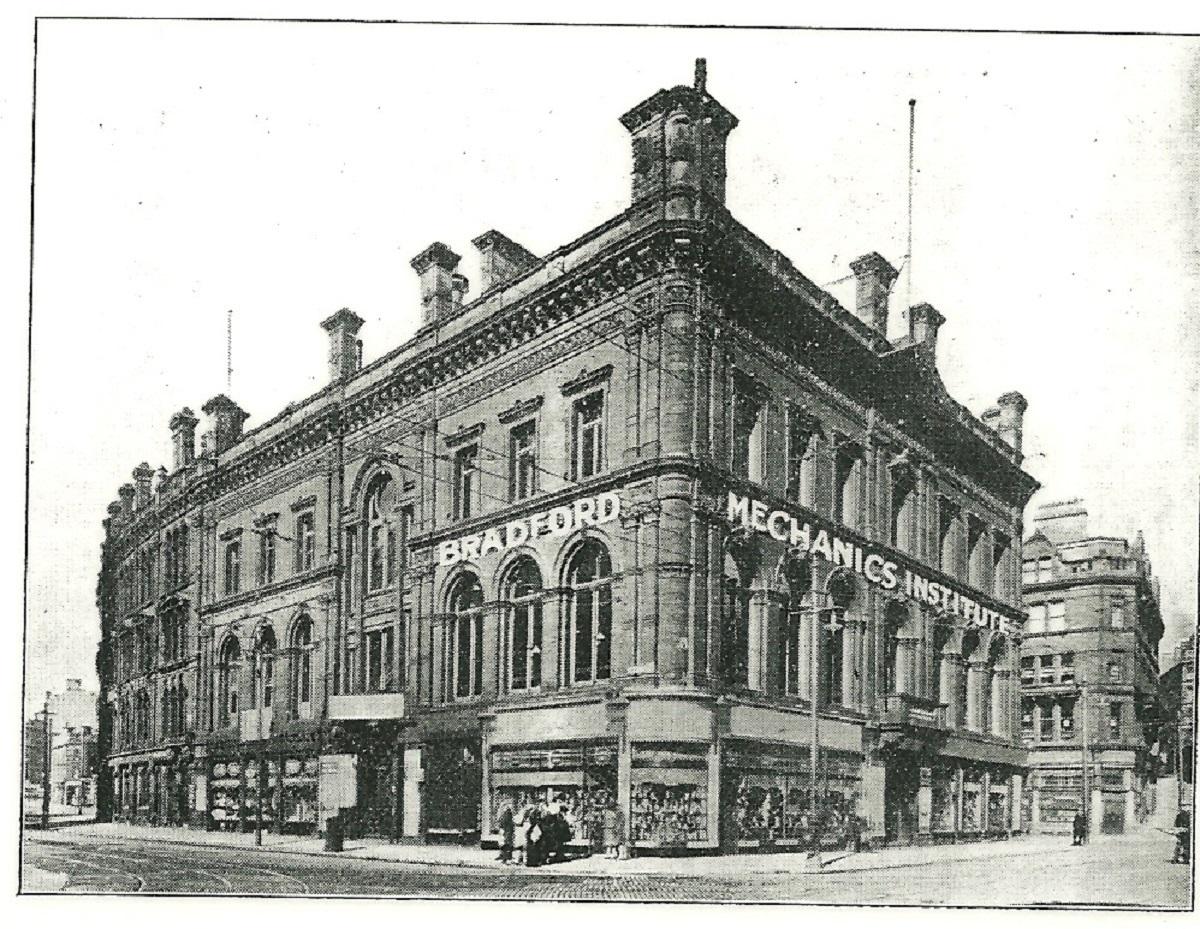

The Purity Campaign moved to Bradford Mechanics Institute where a meeting of women was chaired by Mrs FT Woods, wife of the Vicar of Bradford, who said: “If any lasting good is to be done, one standard of morals for men and women alike must be insisted upon. Women have always been the sufferers through men’s impurities.”

During the First World War Dr Sharp was often called upon to advise charity groups providing ‘comforts’ for war patients. In December 1915 at the Mechanics Institute she addressed a meeting of women making surgical dressings and gave a lucid explanation of disease by bacteria, showing how essential sterilisation was to treating wounds.

Dr Sharp believed wholeheartedly in women’s suffrage. In 1923 she was invited to speak at a dinner given in Leeds for Lady Rhondda, a former militant suffragette. Dr Sharp’s speech called for a scientific inquiry into the physical effects which different kinds of work had on women. Preconceived notions of ‘suitability’ of women’s jobs had so far been proved incorrect. Infant mortality was not higher when women worked in factories and Dr Sharp had been surprised to find an improvement in the health of women who worked in munitions during the war. Sedentary work often had a negative effect, she said, compared with manual labour.

In the mid-1920s Margaret became active in the British Empire Cancer Campaign. She was the principal speaker at a Mechanics’ Institute meeting in October 1930, commending work at Bradford Royal Infirmary which had secured £15,000 worth of radium “now being administered under well-nigh perfect conditions”. This would be the treatment of the future in dealing with cancer. The audience insisted on giving to the Royal Infirmary Radium Fund. A bowler hat went round and £4.3s poured into it.

In 1938, on the eve of war and at the instigation of Home Secretary Samuel Hoare, the Women’s Voluntary Service was formed. Leadership in Bradford fell to Dr Sharp whose wide-ranging duties included: “providing support to the armed services and to refugees, to the evacuation of children, pregnant women and other vulnerable people from cities at risk of bombing.” Dr Sharp’s name is linked to appeals for munitions girls, the recruitment of women drivers for ARP duty and providing for evacuees. In 1940 Bradford received evacuees from the Channel Islands; the families were housed in empty or part-furnished houses and Dr Sharp expressed disappointment at the poor response to her WVS appeal for much-needed ‘household requisites, cooking utensils, bed linen, perambulators’.

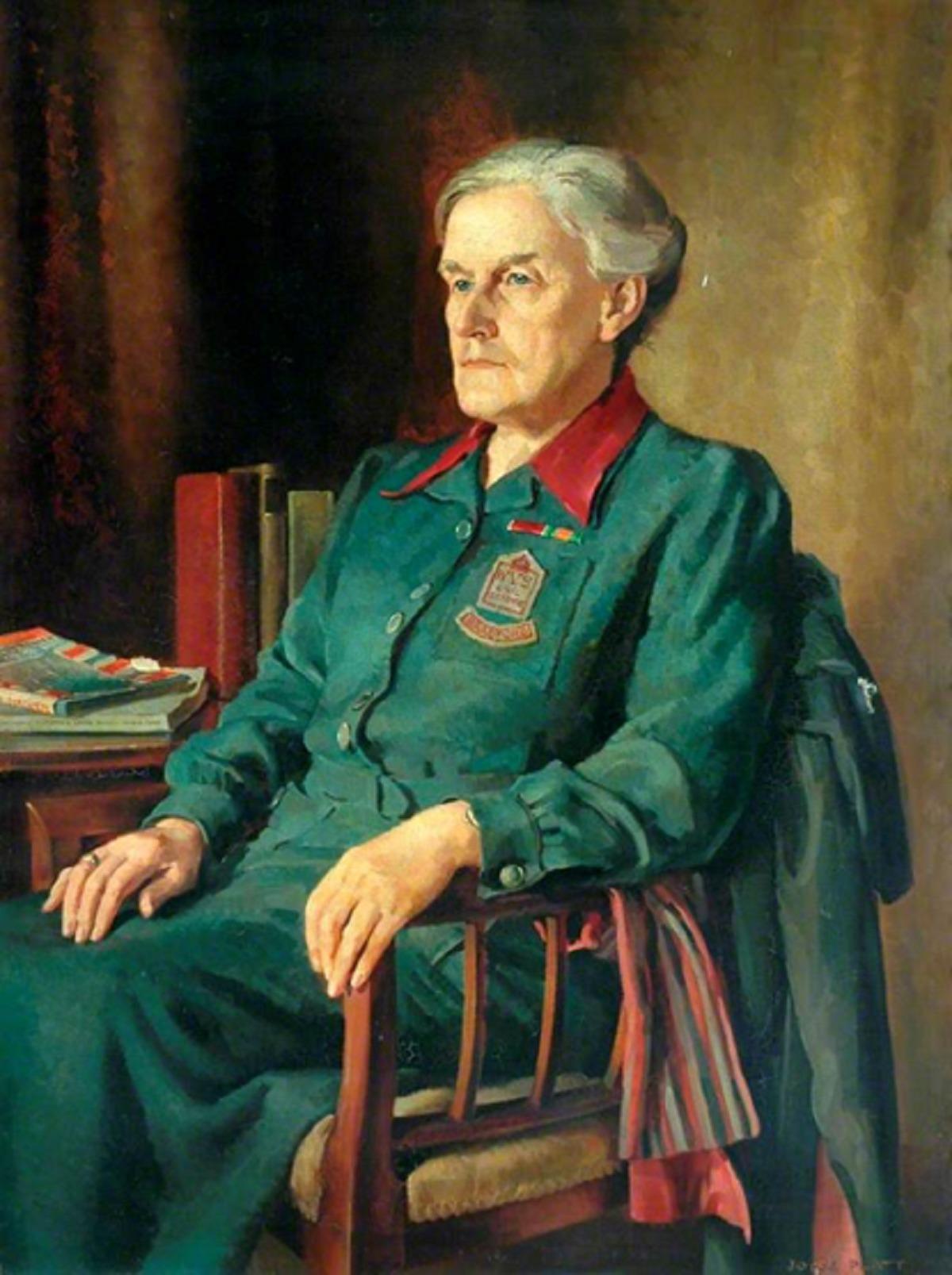

In 1943 she was awarded the MBE. Recognition in Bradford came in October 1946 when Lord Mayor Kathleen Chambers called a special meeting in the Council Chamber, attended by civil defence workers as well as councillors, to pay tribute to Dr Sharp as WVS founder and organiser in Bradford. One after another, speakers rose to acknowledge her devoted voluntary service, ranging from co-operation with the Civil Defence Emergency Committee to the salvage effort. The Chief Constable revealed a wartime secret: the WVS had worked with the police in assembling in Bradford all alien women and children north of the Trent before they were sent to the Isle of Man. The meeting ended with the unveiling of a portrait which was hung in the Town Hall as a memorial to Dr Sharp’s work. Her response was typically forthright: “Voluntary service is more elastic and adaptable than officialdom can ever be...it would be a disaster if it were to cease.”

The work of the WVS continued, with the distribution of tinned food to old people and Dr Sharp’s appeal for part-time workers to help care for children at Bradford’s Fever Hospital. In 1951 announced the start of Meals on Wheels in Bradford. A van was loaned and the first meals were taken to 23 invalids. By March 1955 the register of old people in need stood at 3,986, the demand for meals on wheels remained ‘very great’. Darby and Joan Clubs continued to be set up to relieve loneliness and Dr Sharp (about to celebrate her 85th birthday) organised a hobbies and handicrafts exhibition for the Yorkshire Council for Old People’s Welfare.

Dr Sharp died in 1963, at 93. It is a surprising oversight for there to be no blue plaque to this woman who, although not a Bradfordian by birth, spent her entire career in the city, contributing to every branch of medicine, dedicated to voluntary service and supporting every charity concerned with the welfare of people. The 150th anniversary of her birth in 2021 might be the time to put the record straight.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here