‘GOD made each maid a husband, But men on Earth must fight. So just in case there aren’t enough, He made Miss Florence White’ (Virginia Nicholson).

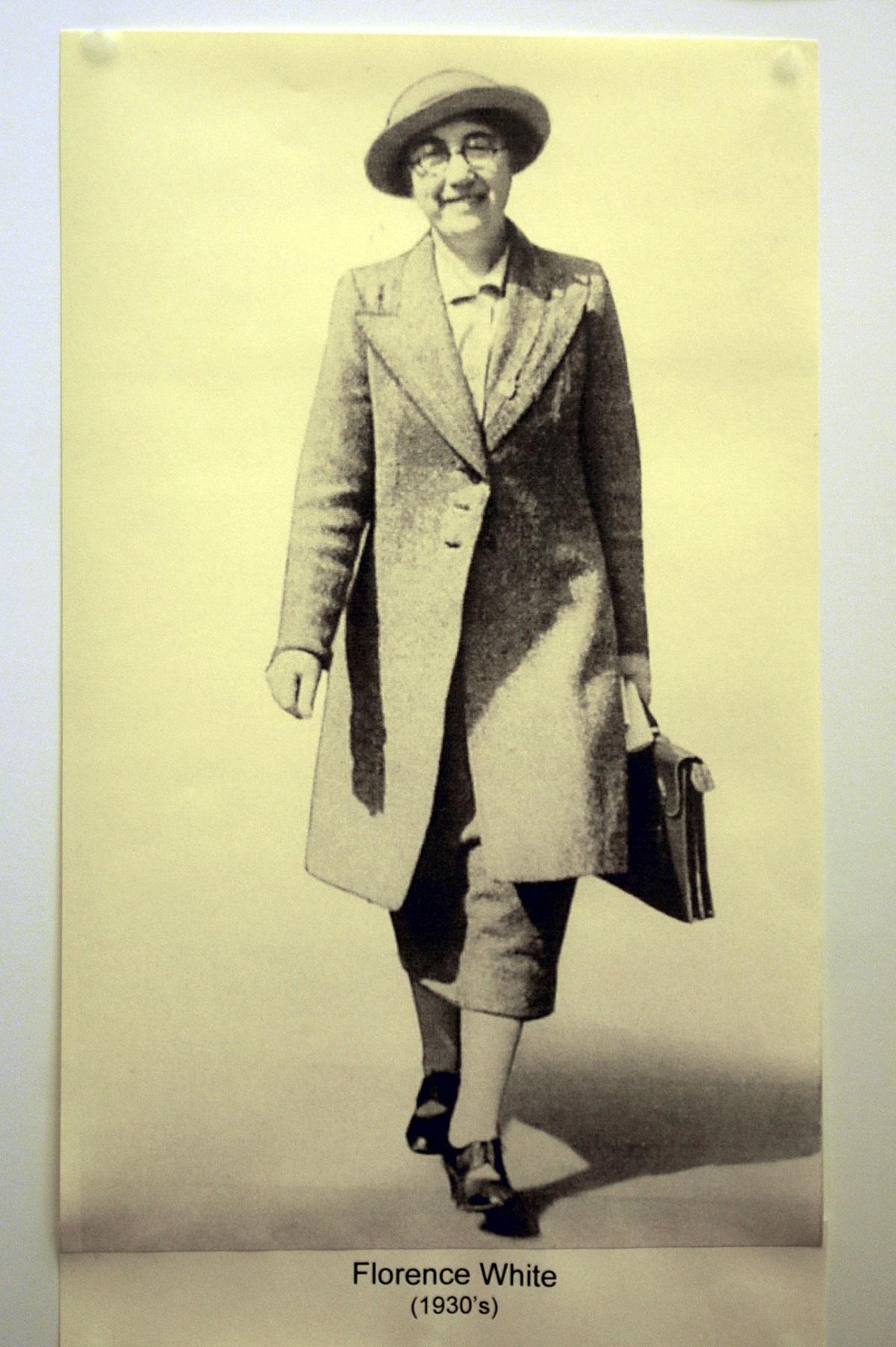

Florence White was a change maker, women’s rights activist and pensions campaigner. In light of recent campaigns by WASPI and in a society where 58per cent of unpaid caring is still carried out by women, the story of Florence seems timely.

She was born on June 11, 1886, in a back-to-back in Furnace Street, Bradford, to an illiterate mill-worker mother and political radical father, who died in Newcastle gaol. By the age of 12, Florence was sent to work 12-hour shifts in in Tankard’s Worst Mill in Bowling.

A key moment in her life was in 1917, when her fiancé Albert contracted pneumonia at the Front and died. In her book Singled Out, Virginia Nicholson discusses challenges faced by women after the Great War, which almost wiped out a generation of young men. This had a seismic effect on women born between 1885 and 1905, brought up with the expectation that their lives would be defined by marriage and motherhood. Headteachers at the end of the war would tell female students that nine out of 10 of them were unlikely to marry and they would have make their own way. The 1921 Census revealed nearly two million single women; considered a huge problem by society and referred to as ‘the surplus women’. Ten years on half of them were still unmarried. Whilst the war had created more opportunity than ever for women in the workforce, many professions were still shut off to them. And as men returned from the Front, women faced additional pressure to withdraw from the workforce. Single women experienced prejudice. But Florence was not going to passively accept this, nor be labelled a victim, instead she chose a different path, campaigning for social change. And as such she deserves the accolade of hero: not just that but a forgotten Bradford hero - one of the groundbreaking women of the past 100 years.

Florence joined the Liberal Party and immersed herself in local politics, becoming party Secretary in the South Bradford ward. She developed thoughts and skills that proved useful championing women’s rights and fighting for social change. In the 1920s and 1930s many spinsters were not eligible for state pensions. Those who were eligible often died before they could receive their pension at 65. Women had fewer employment opportunities and when they were employed, were paid less. And many unmarried women had additional caring roles, juggling looking after ageing parents with a busy working life.

In 1935 Florence established the National Spinsters’ Pension Association. It had two main aims: to reduce the state pension age for unmarried women who could make National Insurance contributions from 65 to 55, and to provide entitlement to a contributory pension for those excluded from the scheme. Florence was living with her sister Annie above their small confectioner’s shop at 21 Scholemoor Lane, Lidget Green, and it is from here that they carried out much of their campaigning and drafted Florence’s speeches. This property remains, and is today a convenience store.

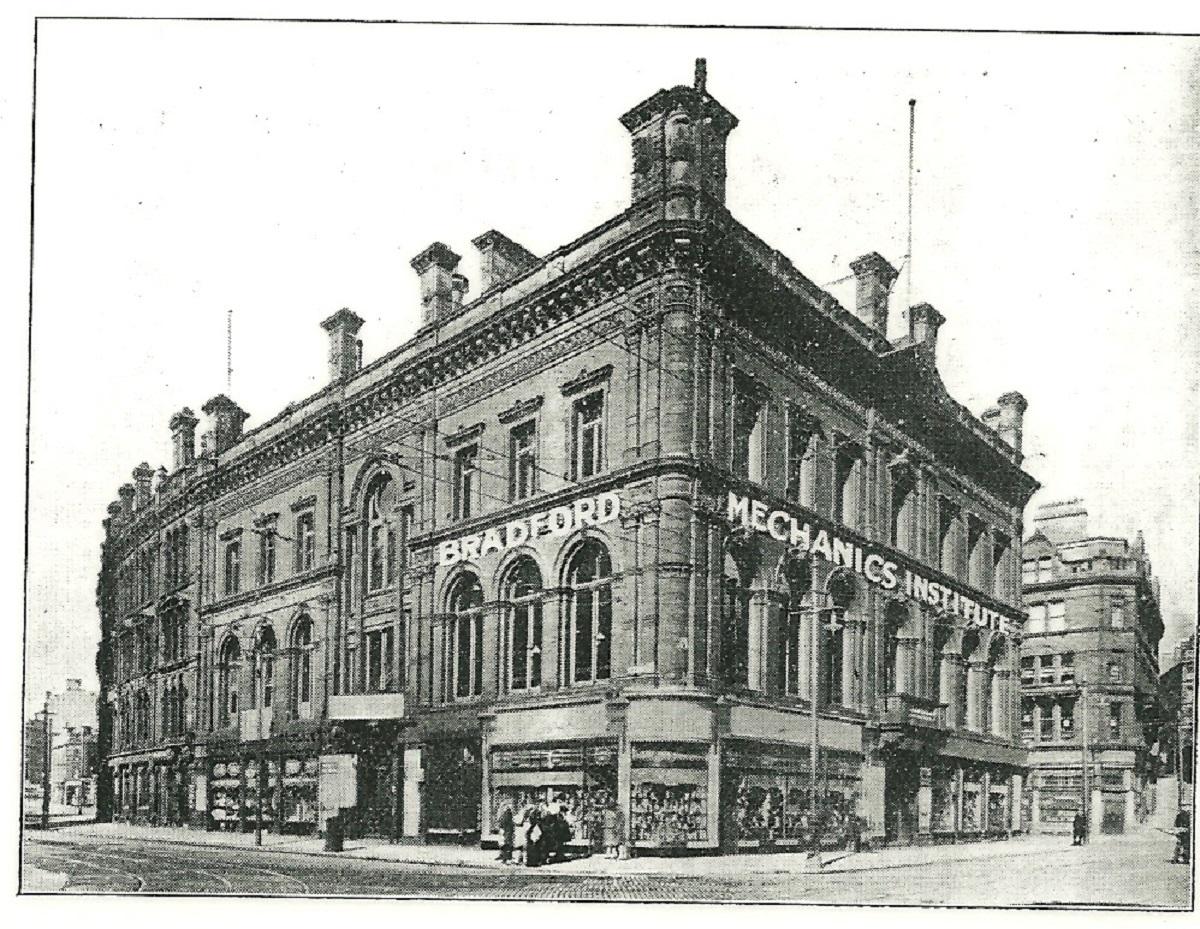

The National Spinsters’ Pension Association’s slogan was ‘Equity with the Widow’. Widows were entitled to their pension at any age, whilst an unmarried woman might make contributions but not receive her pension at all. The Association first met at Bradford Mechanics’ Institute on Bridge Street to a packed audience of 600, mostly working-class and single. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that this movement began in Bradford, since women comprised around three quarters of the textile industry’s working population. Many single women had to work up to 65 before receiving their pension. In addition, women had to keep up with weekly contributions to the age of 65, and if unable to their previous contributions were discounted. They were in danger of having to fall back on Public Assistance. Many older women in mills were unable to keep up with changes to working practices and increased demands and lost their jobs to younger women. Dire poverty was not uncommon in a group often invisible to society.

In the two months following its first meeting, the Association had become organised nationwide. By December 1935 there were 16 branches across the North. In a 1938 edition of Picture Post Florence White said: “The young and the wise get into the protected industry of marriage”. There were around 175,000 not so young and wise, aged 55-65, and it was for these women, that Florence was fighting, particularly since just 80,000 qualified for a pension. She said unlike the Suffragettes they weren’t planning a campaign of militancy, but would instead be seeking “constitutional ways” to effect change.

The National Spinsters’ Pension Association became hugely popular; membership swelling to over 140,000. The campaign gathered momentum, with rallies across the UK. Letters were sent to MPs, and in 1937 20,000 spinsters sent Minister of Health Sir Kingsley Wood a Christmas card. A procession of more than 1,000 women wearing shoulder straps of broad white ribbon marched through London, selling ivy leaf badges with the slogan ‘Pensions at 55’. A petition was escorted to Parliament by Florence, travelling by decorated lorry from Bradford. Hansard reveals the petition was discussed on July 27 1937 where the ‘grave hardship and injustice’ of the old age pension not being payable until 65 was expressed. It was claimed the petition was signed by a million people in a month, men and women, married and single, described as ‘clear evidence for the widespread support for the spinsters’ cause’. Florence sought publicity and was escorted from the House of Commons by police after holding a demonstration with cries of “Justice for spinsters!” Eventually a Parliamentary Committee was created, sitting in the Royal Courts of Justice to consider the spinsters’ plight. Florence spoke for over three hours, repeatedly cross-examined.

By 1940 the pension age for women was reduced to 60. The Association celebrated at Bradford’s Connaught Rooms. The movement Florence had begun had challenged social injustice and brought about change. More than 150,000 spinsters would receive a pension of 10 shillings a week. But the payments were still meagre and the initial aim of reducing this to 55 would never be realised. After the Second World War, the Labour government set up a new pension system and the National Spinsters’ Association was wound up in 1958. Florence died in 1961. At her funeral members from Yorkshire branches filled the chapel at Bowling Cemetery. The Reverend D Wade said “many of those present and many hundreds who were not would have reason to give thanks for her work”. Her obituary in the Telegraph & Argus described her as ‘the champion of Britain’s spinsters’.

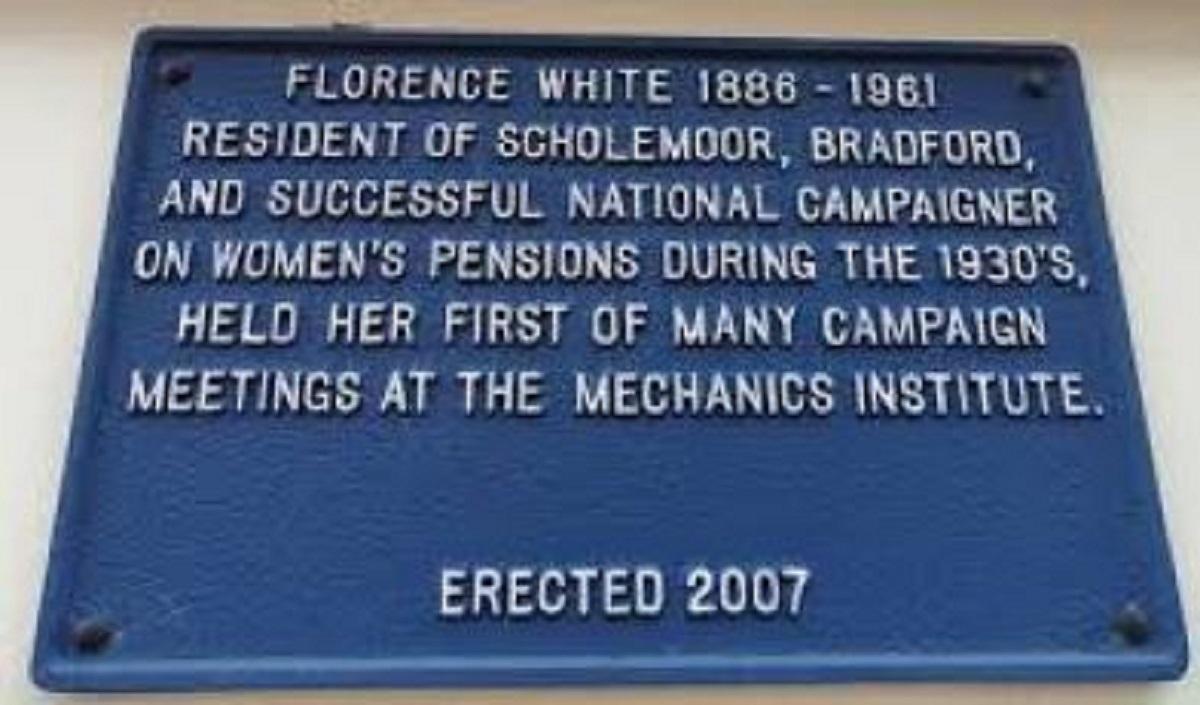

An often overlooked aspect of her life is that she also worked for peace. A blue plaque commemorates her at 76 Kirkgate, included in the Bradford Peace Trail. With thanks to the Local Studies Library.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel