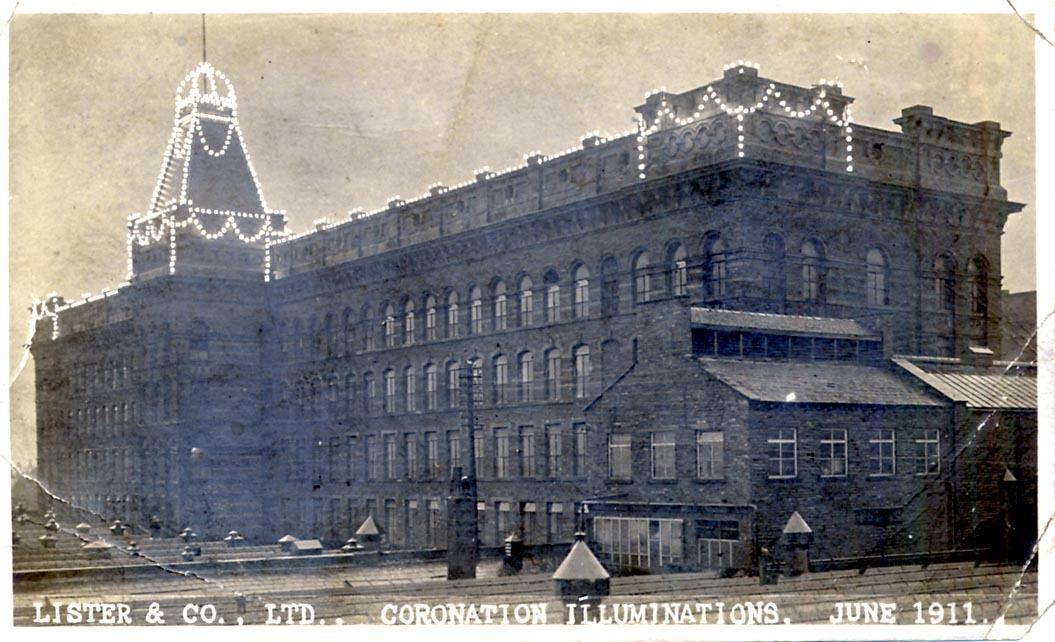

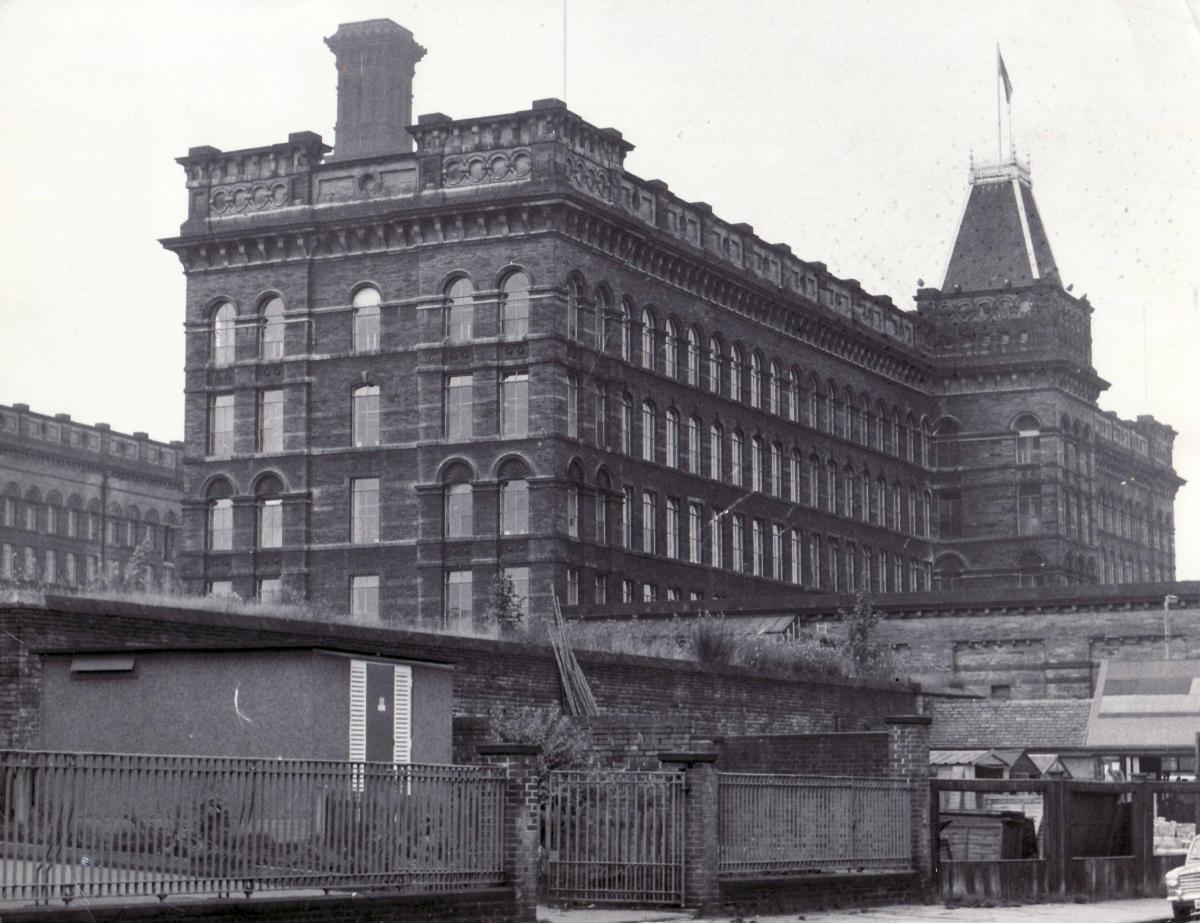

LISTER’S Mill has dominated the Bradford skyline since it was built in grand Italianate style in 1871.

Built by Samuel Cunliffe Lister to replace a mill that had burned down on the Manningham site, it was the world's largest velvet and silk factory in the world - an industrial giant when Bradford was leading the way in textile manufacturing.

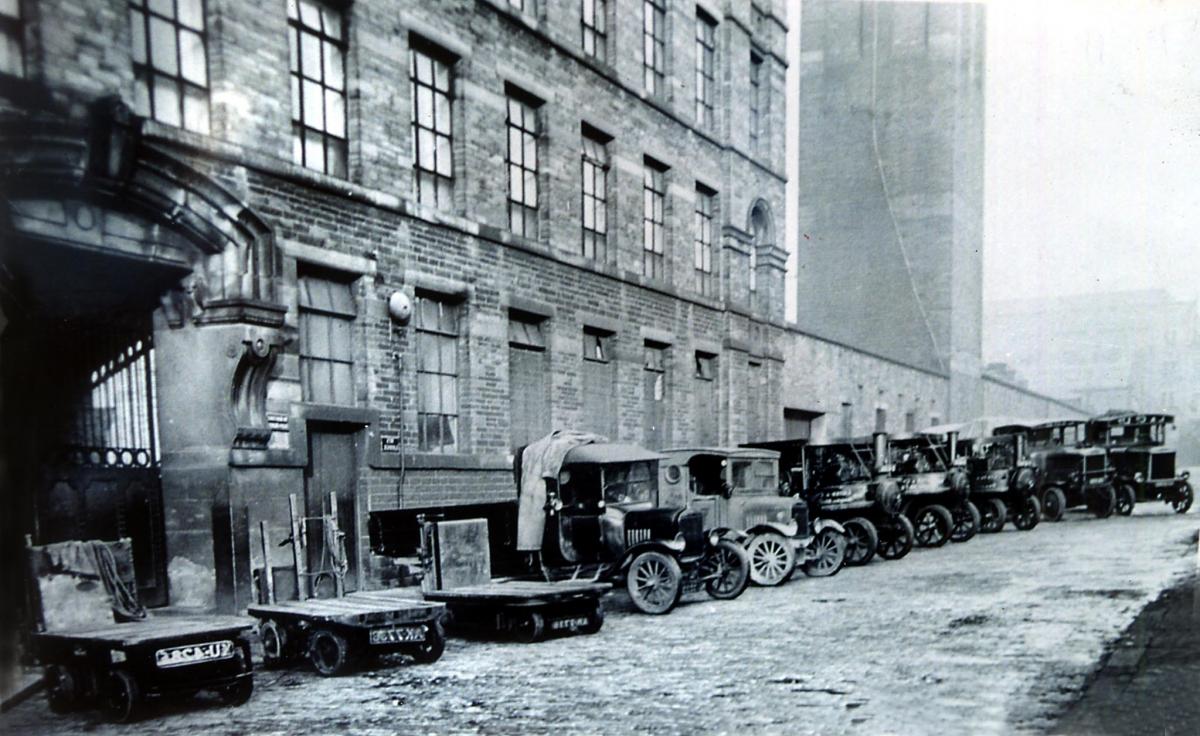

Now home to residential, business and community use, the sprawling site was the largest mill in the north of England, with 27 acres of floor space and its imposing 249ft high chimney.

The great Manningham Mills strike in the early 1890s led directly to the founding of the Independent Labour Party.

Lister’s supplied 1,000 yards of velvet for King George V’s Coronation in 1911 and in 1976 new velvet curtains for President Gerald Ford at the White House. During the Second World War it produced 1,330 miles of parachute silk, 284 miles of flame-proof wool, 50 miles of khaki battledress and 4,430 miles of parachute cord.

At its peak Lister’s employed more than 11,000 men, women and children. It had its own doctor’s surgery, theatre club and social events committee.

By the 1970s it was still employing more than 4,500 people but the recession of the 1980s, coupled with a decline in the UK textile trade, took its toll and it closed in 1992. Developers Urban Splash bought the mill in 2000 and carried out extensive renovations, turning part of the historic building into chic apartments.

Many people in Bradford still remember working at Lister’s Mill, or recall their parents and grandparents working there.

Here, Dr Paul Jennings, looks back on parties held for the children of workers at the mighty mill complex. He and his brother attended festive parties there in the 1960s, and enjoyed carol singing, comic turns and a gift from Father Christmas himself:

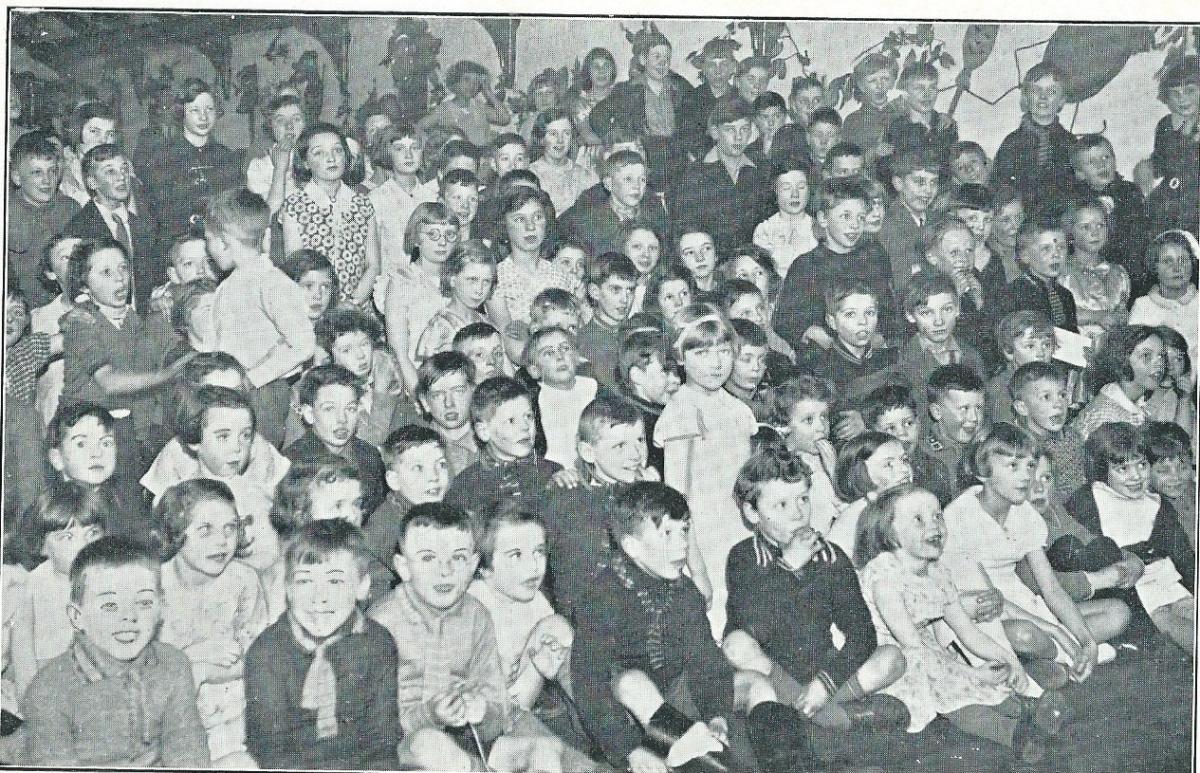

“The happy faces here are of children at one of the two Christmas parties held at Lister’s Manningham Mills in late December 1934, pictured in the Lister’s Magazine of January the following year.

A total of 400 children enjoyed tea, followed by carol singing and entertainment consisting of Punch and Judy, conjuring and performing dogs, plus Miss Mary Corcoran who danced and Master Row, who sang. Father Christmas presented gifts to the departing children to the accompaniment of bagpipes.

Christmas was a key date in the incredibly varied social, cultural and sporting life enjoyed by Lister’s thousands of employees.

The children’s parties had been started in 1927 but the oldest Christmas event was the singing of carols and hymns, which also sometimes included ‘On Ilkla Moor Baht’At’. It had been inaugurated back in 1878, not long after the completion of the colossal mill complex. For 50 years, beginning in 1896, it was conducted by Mark Mountain, a foreman in the velvet weaving department. At the 50th Annual Christmas Sing in 1928 over 2,000 employees met in Heaton Shed to be led by Mr Mountain wearing his customary velvet jacket. He handed on his baton in 1931 on his retirement, but always returned to conduct ‘Hail! Smiling Morn’.

He came back then for his final appearance at the 71st event in December 1949 in his 88th year, with the Manningham Mills Choir and Lister’s Melodic Orchestra.

Another Christmas event was the pantomime, first staged in 1929 with a performance of Robinson Crusoe, written and produced by Mr G E Jubb.

Readers of the book may be surprised at the cast list of 15, headed by Ethel Binns of velvet weaving as Crusoe and including Mary Tate from spinning as Mrs Crusoe. It was reprised 20 years later after the more familiar fare of Cinderella, Aladdin, Jack and the Beanstalk, Dick Whittington and Red Riding Hood. My dad played Man Friday.

As children of an employee, my brother and I attended the Christmas parties in the 1960s, and I well remember the tea, the carol singing, the comic turns and magicians and the present from Father Christmas at the end.

There were still around 300 children. Lister’s remained a big employer but there were signs by then that the social world was beginning to fade. Sports teams ceased their connection with the company; the Entertainments Committee began to complain about the lack of support, for example in 1963 for the lunchtime films and concerts.

The difficult times which the industry faced, especially from the 1970s, led to a marked reduction in the workforce, whose composition also was changing with the arrival particularly of men from south Asia. At the same time, new patterns of leisure with greater affluence, especially as it became more home-based with the advent of television, undermined work-based social and cultural pursuits.

Well before the Manningham Mills finally closed in 1992, the word of communal singing, pantos and parties had gone.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel