IN 2011 Ed Caesar read a paragraph about a Yorkshireman who, in the 1930s, decided to mount an ambitious expedition to climb Mount Everest.

The man planned to fly a plane from London to the lower slopes of the mountain and walk the rest of the way to the summit - despite having no flying or mountaineering experience.

When news of his outlandish scheme became public he was forbidden from carrying it out, but defied authority and embarked on a mammoth trek, flying thousands of miles, walking hundreds more - in disguise to evade arrest - and tackling the inhospitable terrain of the world’s highest peak.

Incredibly, his bid to make the pages of the history books, failed only in its final chapter.

That man was Bradford-born Maurice Wilson, and his story of derring-do struck a chord with author Ed, who set out to tell the fascinating tale it was.

‘He had hardly climbed anything more challenging than a flight of stairs,’ he writes of Maurice, the son of a middle-class businessman who had worked his way up in the textile industry from a factory boy to a mill owner. 'Everest was a kingdom of ice, snow, crevasse and serac.'

Raised with three brothers in Cecil Avenue, a street of spacious homes in a respectable neighbourhood of Bradford, Maurice was a bright child, leaving Carlton Road Secondary school speaking fluent French and German.

In the years preceding the First World War, Bradford was a ‘thrilling’ place to live. In the summer of 1914 the city hosted the Great Yorkshire Show, whose star attraction was what was billed as the ‘world’s first passenger air service’, with a plane ferrying single passengers between Bradford and Leeds.

The change in the city brought about by the conflict affected Maurice, who then worked as a clerk at his father’s mill.

‘Maurice Wilson saw how the war had made his city gloomy,’ writes Ed,’ ‘As a sixteen and seventeen-year-old, he walked to work through Horton Park, whose bandstand was no longer thronged with weekend suitors; past the cottage-style roof of the Bradford Park Avenue football stadium, whose excellent team no longer played matches; past pubs that now shut early at 9pm.’

Aged 19, he joined the army and fought in the Battle of Passchendale for which he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. He was later seriously wounded - his left arm never properly healed - but his attempts to secure a war pension - as his brother Victor had - were unsuccessful, something which rankled with him.

Maurice married, but wasn’t the best husband. ‘Even as he was preparing to marry her, Wilson was already planning his escape,’ writes Ed. He sailed to New Zealand, where he met his second wife who ran a successful fashion business.

This union also failed and there followed a life in which he moved across continents, always restless. Back in England, he met a married woman Enid Evans, for whom he developed a lifelong attachment and wrote touching letters while on his travels.

The story thereafter puts Eddie the Eagle’s escapades in the shade. Previous official, well-supported expeditions to Everest, with lavish supplies - the 1922 expedition stores had filled 900 plywood boxes - had failed.

Maurice thought this all too burdensome and believed he could claim the summit on his own. ‘What if one man, trained in body and spirit, and unburdened by yaks and porters and foie gras, attempted to climb the mountain alone?’ writes Ed. ‘Would he not stand more chance than these slow-moving armies?’

In 1933, after hatching his plan - which he called ‘the show’ - Maurice bought a three-year-old De Havilland Gipsy Moth from the Scarborough Flying Circus, which he called Ever Wrest.

Moths had become very popular, being easily stowed, reliable and capable of flying long distances. And, crucially, it was the plane used by Amy Johnson to fly from London to Australia.

Maurice's training was physically demanding - more than once to walked between London and Bradford in hobnail boots. To garner some climbing experience, Maurice spent a few cold weeks hiking in the Lake District and Snowdonia, ‘but he made no effort to learn the basic Alpine techniques he would need: ice cutting, climbing in crampons, the use of the axe.’

He took flying lessons, his teacher being ‘horrified by his pupil’s stated objectives’ and the fact that he had just two months to teach a beginner into a flier able to traverse the globe.

Later that year, Maurice tested his bravery with a parachute jump, hurting his feet badly. His resulting limp led to the stories in the Press. The tale captured the public’s attention, but also alerted home and foreign governments, who tried to stop him in his tracks.

But his plans were not to be scuppered by officialdom. ‘Stop me? He told reporters. ‘they haven’t got a dog’s chance!’

After a delayed departure - in which he crashed his plane in a field in Cleckheaton - Maurice took off from London, flying 5,000 miles to India, where his plane was impounded.

Bad weather meant he had to wait until the following year to make an attempt on the mountain.

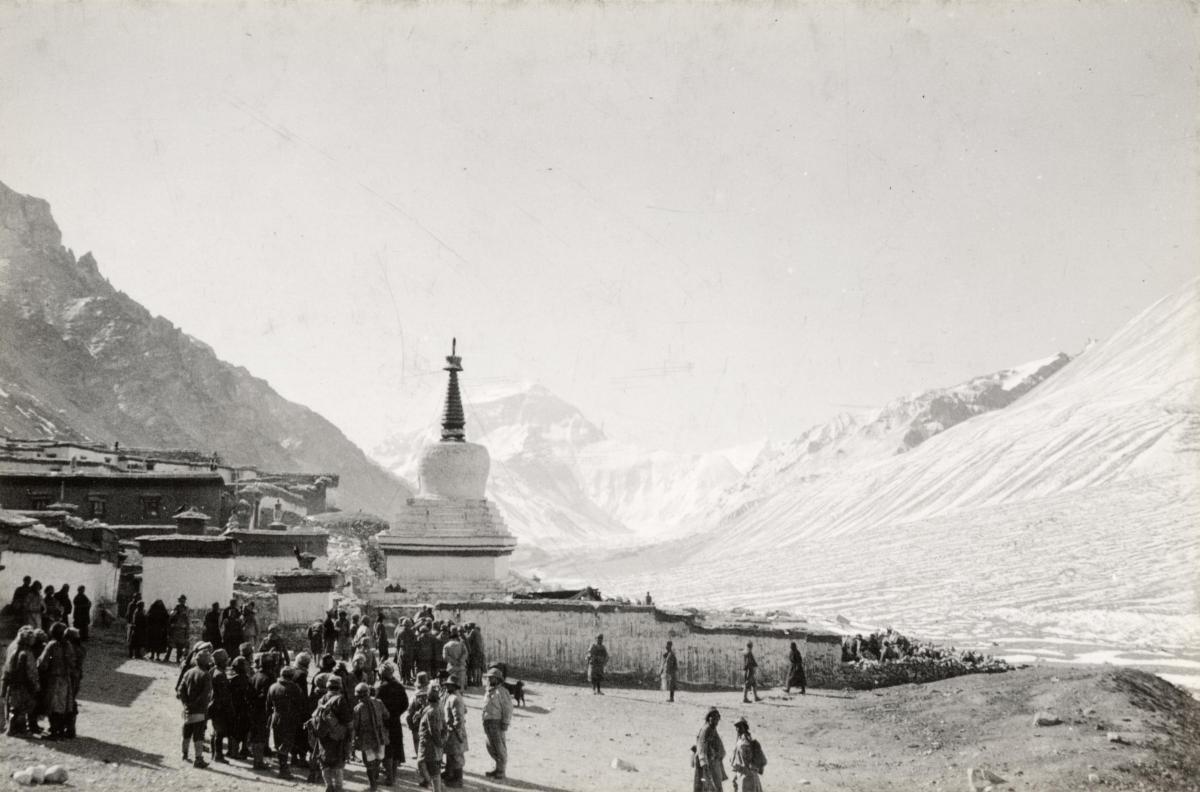

To evade detection, he adopted a disguise for his final trek through Tibet on foot - a ‘dazzling’ priest’s outfit of a Chinese brocaded waistcoat in gold, with gold buttons at the side.’ Maurice thought it made him look like a circus trainer.

‘He wore a fur-lined Bhutia hat, with large ear flaps to cover his white man’s hair, dark glasses to hide his white man’s eyes, and he carried a decorative umbrella.’

His Yorkshire roots were never far away: ‘Somewhat ruining the effect, he also wore a pair of hobnail boots.’

He was clearly fun, with a sense of humour evident in the entries he diligently wrote in his small green leather diary. ‘Just had wholemeal bread. This stuff will play no small part in success. Pity the chappie is keeping it so near his socks in his rucksack.’

In researching the book, Ed met Maurice’s great-nephew, who as well as providing him with documents and photographs relating to his great-uncle, ends up wide-eyed on hearing things he had not previously known.

Incredibly, Maurice’s dream of climbing Everest was by no means a failure. In April 1934, aged 36, he at last stood at the foot of Everest.

When he camped on his first night on the mountain, ‘with only an indifferent meal of lukewarm Quaker Oats in his belly’, he felt success was close’, writes Ed.

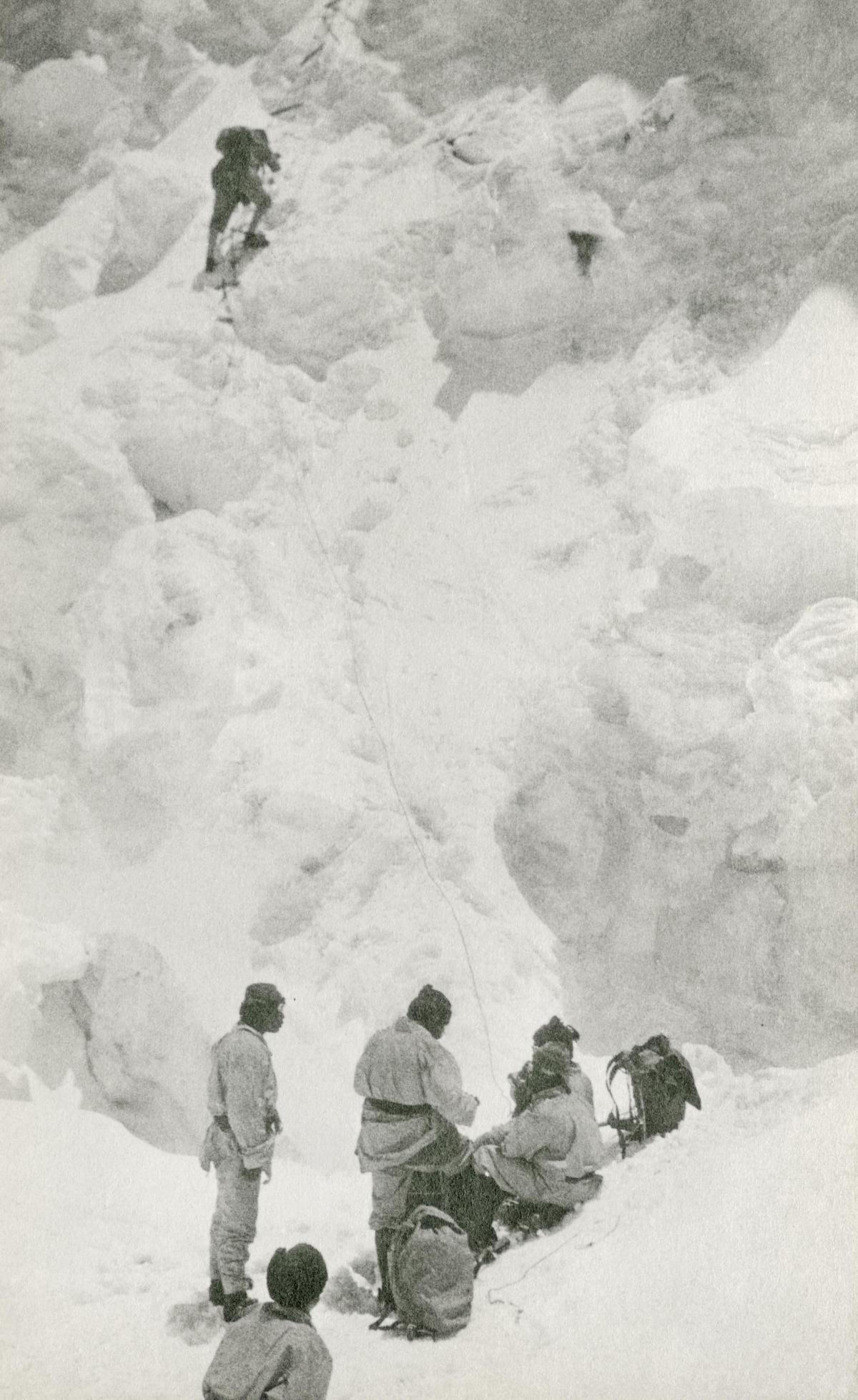

His first attempt, alone, was halted by a snow-storm, but the second, with two Sherpas in tow, got off to a better start. After the Sherpas turned back due to their weakness after days in exposed conditions, and the dangers ahead, Maurice pressed on, ascending to almost 23,000ft. He did not return. His last legible diary entry, dated May 31, reads ‘Off again, gorgeous day.’

Maurice’s body was found by a climber a year later at the bottom of Everest’s North Col. He was wearing clothing a jumper, grey flannel trousers, a woollen vest and pants underneath. Nearby was his rucksack containing his diary. He was buried in a crevasse, the spot marked by his ice axe.

*The Moth And The Mountain: A True Story of Love, war and Everest by Ed Caesar is published by Viking priced £18.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here