EARLY on Day Two the Bradford Daily Telegraph reporter was again in Girlington to check on morale following the men’s first night under canvas. Although one or two appeared to have stiff necks, one land-grabber said: “It’s nowt, we’re all as lively as rats in earth, and as ‘arty as ‘ares.”

A second tent arrived at the Bradford camp from London. Several men went to obtain picks and shovels to commence their work which turned out to be arduous as the land was difficult to break up. They also set to repairing a wall surrounding their camp. The reporter described the difficulties experienced by a dyer’s labourer in undertaking this task, especially as “the mortar is conspicuous by its absence and not even a trowel or a pick or any implement is to be had”.

A large crowd, reported to be ‘clerical types’ stood watching. With the arrival of Charles Glyde,who had got the Bradford land grab underway, a meeting was called for him to instruct the men “to carry on your work” as though he was there. “Don’t smoke during hours, and never stand idly in the field.” Their day was strictly timetabled - work from 6am, breakfast at 8am, work from 8.30am-12.30pm, dinner: (tea and bread with butter) then work from 1.30 -5.30pm.

The Manchester land-grabbers were quick to offer their support to their Bradford brothers. A small deputation, including Stewart Gray and Arthur Smith, visited on July 25, and a large crowd gathered to hear speeches from movement organisers. Gray said he was fighting for the rights of the unemployed; if they were unable to find work they should be given the opportunity to obtain food for themselves and their families. Likening the movement to Moses and the children of Israel he said: “Our rights must be obtained by blood if needs be.” Glyde took the stage and said he’d heard the landowners were going to turn them off but “we can easily flit.” Days later, a storm struck and the Telegraph reported that one of the men, an ex soldier, had organised trenches to be dug around the tents to run off the water.

The land-grabbers continued to catch the attention of Bradford people; from early morning until late at night there was a steady stream of curious visitors and there were animated debates concerning the ethics of land-grabbing, and whether better provision should be made for families of the unemployed.

Ever since the start of the land grab there had been speculation over what moves landowners the Midland Railway Company would make. On the Thursday three representatives of the company visited the site and asked the men to leave. The reply was that the men refused to leave until they were expelled. The Bradford City Guild of Help, along with Stewart Gray, organiser of the Manchester land-grabbers and an adviser to the Bradford men, met with the company, wanting it to guarantee not to evict the men for 12 months. In the meantime the men intended to use stones littering the land to build a temporary building for winter. There were more storms and the effects on the camp varied depending on which newspaper you read. According to the Bradford Daily Telegraph, the storm played havoc with the tents and mattresses were “in a pitiable condition” with the floor covered with wet straw and “resembling a pigsty”.

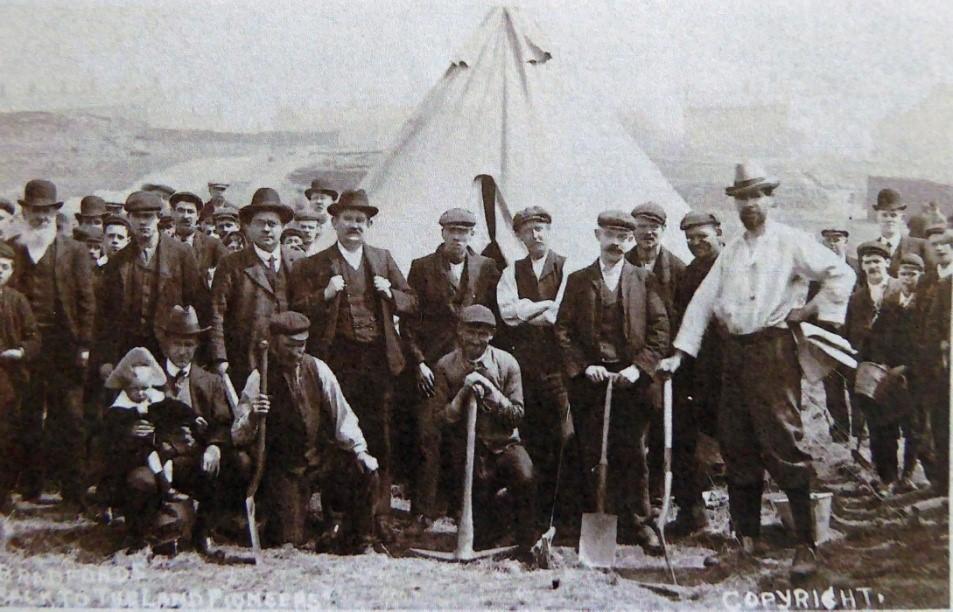

By the start of August 17 men were at the camp and a third tent arrived. On August Bank Holiday large crowds gathered to watch the men and it was reported that they were quick to take advantage; selling picture postcards they’d commissioned. The camp was frequently used by demonstrators to show their support for the movement. Large crowds gathered and hymns were sung by the Socialist Sunday Schools.

The water supply was a problem for the squatters. In the early days local people were happy to supply them with water but they soon withdrew. The men found a trough on City Road and made long journeys carrying water in buckets. Eventually an old well was discovered on the site and after a bit of work it was brought back into use. Although the men seemed to be working hard with a spirit of collaboration the Leeds Mercury reported that one of them shared news that a deceased relative had left him £5,000, which he intended to divide among his comrades. By the following morning the man had disappeared, never to be seen again.

On August 27 Labour MP FW Jowett attended a meeting at the Whetley Lane site. Full of his praise for the men, he avowed his support for the back-to-the-land movement and said Bradford had over nine-and-a-half square miles of land, apart from the newly acquired Esholt Estate, which could be utilised by unemployed men and “render them independent of the woolcomber capitalists”.

The camp fell into a routine of tilling the land, holding meetings and engaging with interested visitors. Despite a dispute between newspapers about the success of the venture, it was reported that that cabbages, cauliflowers, celery, lettuce and turnips were growing well. The men were eating food they’d grown and even selling some to visitors.

By the end of September it was reported that the camp had been visited by over 100,000 people who had donated £51 15s. 1d. Over 80 open-air meetings had been held. Corporation officials reported that no plans had been submitted for the camp building and the men received a letter warning them to cease building at once. This marked the beginning of the end for the camp. The men had to face facts that without a robust building they wouldn’t survive the coming winter. One by one they began to leave and by the end of October there was nothing for Glyde to do but find a buyer for the equipment and consider his further moves to promote the welfare of the unemployed.

And so the great Bradford land grab came to an end. But this is not quite the end of the story. Whilst the occupation was underway there had been discussions concerning the plight of the unemployed. The Bradford City Guild of Help obtained six acres of grazing land in Eccleshill to turn into allotments. Gray soon had his band of men hard at work removing the turf and erecting a dwelling. He hoped if this was successful the men could be installed on a proper farm colony complete with stock, poultry and bees.

Although the land grabbing movement was short-lived it highlighted the plight of the unemployed and spurred the new Liberal Government’s social reform programme. In 1907 it enabled local councils to provide free school meals, a measure Bradford was quick to adopt. The 1908 Small Holdings and Allotment Act placed a duty on local authorities to provide sufficient allotments for local demand. In Bradford, Corporation allotment plots rose from 459 pre-First World War to 4,188. School gardens were established and by 1918 51 schools were growing potatoes, cabbages, cauliflowers, beans and peas. These reforms, along with the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, Labour Exchanges Act 1909 and National Insurance Act 1911 were among the first steps towards improving the lives of working men.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel