THINK of Wuhan today and we think of one thing: coronavirus.

The sprawling capital of China’s Hubei province is home to the 5,000-bed Wuhan Union Hospital, one of China’s biggest hospitals and the specialist research centre for the virus.

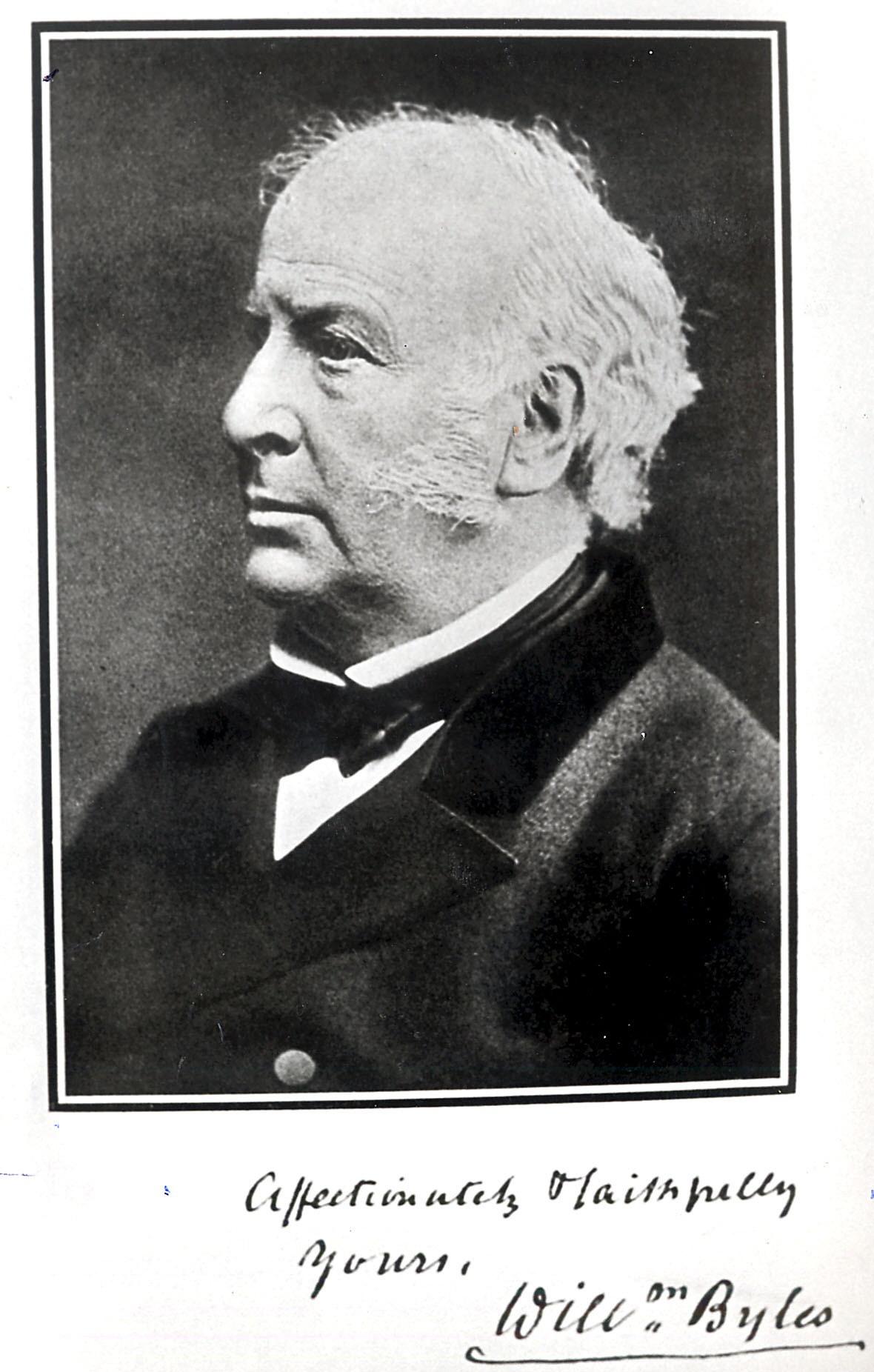

It was a very different place when Dr Hilda Byles - granddaughter of William Byles, founding editor and proprietor of the Bradford Observer - worked there as a missionary and doctor in the early 20th Century. It was while researching a local First World War soldier that Tricia Restorick discovered that his Aunt Hilda had a story of her own.

Tricia, president of Bradford WW1 Group, has supplied this information about Dr Hilda who, despite working in China at a time when missionaries’ lives were in danger, became well respected among Chinese people. Her patients included destitute boat families, prostitutes and lepers.

Hilda’s father, Alfred Holden Byles, was William’s second son and turned away from the newspaper world to become a Congregational Minister. Hilda was born in 1879, one of five children. Two of the Byles brothers, William and Winter, emigrated to America and in 1912 eldest brother, Rousell, who had been ordained, set off to New York to officiate at William’s wedding. Rousell was a passenger on the Titanic. On the morning of April 14, he said Mass and gave a sermon on the need for “a spiritual lifeboat”. Later that day, after the ship struck the iceberg, he helped third class passengers to lifeboats. Refusing a place himself, he heard Confession and gave Absolution to stricken passengers.

While Hilda’s sisters married into textile families, she trained at the London School of Medicine for Women and after graduating in 1904 left England to take charge of the women’s section of Union Hospital, Hankow (later Hankou, one of three cities which merged to form Wuhan). According to Undercliffe Cemetery records, Hilda held the post of Chief Medical Officer from 1910 to 1930.

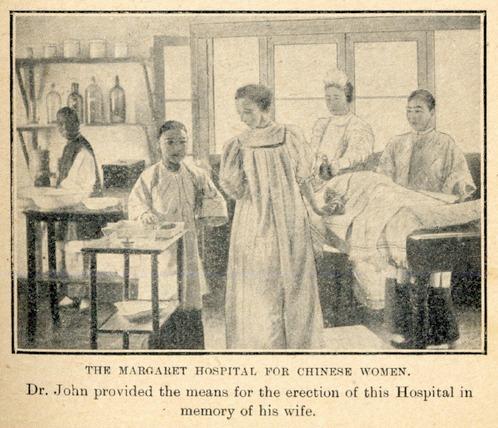

The Hankow hospital was founded by Dr Griffith John, a Welshman who began preaching at 13 and was the first missionary in inland China. After teaching himself Chinese, he travelled to Hankow in 1855 and established two schools and the hospital. He spent nearly 60 years in China, establishing five more hospitals in neighbouring provinces, a leper colony, a teacher training college and more schools. This range of education and health care placed Hankow years in advance of the rest of China. Dr John survived the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, a Chinese uprising which persecuted and killed many missionaries.

Patient numbers increased quickly during Hilda’s time and the hospital moved to a former warehouse in “a district of shed-dwellers and gruel kitchens”. Hilda treated families who lived on sailing boats. A missionary wrote of the place: “The struggle (to get gruel) is so great weak, half-starved women and children often get crushed as they try to approach the door.” At its peak, the network of kitchens was distributing 6,500 bowls a day, funded by Benevolent Halls. In winter numbers were swelled by rural refugees escaping freezing weather. To be available for night calls and other emergencies, Hilda moved out of her comfortable quarters in the British Concession, the banking and commercial centre, and lived in the hospital.

By 1924, she was teaching midwifery practice in rural areas surrounding Hankow, and also worked in the leper colony. She was well thought of among local people, and trained many Chinese women in obstetrics in their homes.

Hilda died of pneumonia in 1931, a month before her 52nd birthday. Her obituary in the British Medical Journal describes her as “a little woman of amazing energy and capabilities”. The China Medical Journal highlights her missionary work and “strenuous self-sacrificing efforts, in many cases successful, for the rescue of girls from a life of shame and servitude. Her own life was more than once in danger from the infuriated owners who kept the girls in thrall.”

Hilda’s funeral took place during some of the worst ever floods in Hankow, with streets submerged for six weeks. Floods were rapidly rising, with streets knee-deep in water, but that didn’t stop a large congregation assembling from the three Wuhan cities to attend Hilda’s funeral in the Hua-Ioa church, festooned with Chinese scrolls.

Her friends and colleagues followed the coffin through the floods to a cemetery a mile-and-a-half away, where a long double line of Chinese people waited with flowers. Hilda’s grave was decorated with a “glorious heap of wreaths and tokens and sweet-scented flowers”.

Also working at the Hankow hospital was Gladys Stephenson, who attended the Ilkley Deaconess College which prepared women to serve Methodism at home and overseas.

Gladys, who died in 1981, became matron of the hospital and headed up the Nurses’ Association in China. She was interned by the Japanese in the Second World War and her journals record her prison camp experiences, as well as accounts of the great floods of China in 1931.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here